Whew, we've survived enough to 2017 to make it to another batch of questions ! Hurrah ! This was delayed by a week due to a work trip. With any luck we'll survive another week for the next batch...

1) What's your take on Verlinde gravity, Rhys ?

I don't like it.

2) Does the Bullet Cluster rule out very weakly interacting dark matter ?

No.

3) Can you take as good a picture with a smartphone as you can with a 500m telescope ?

No of course not, you twerp.

4) How come we can detect planets around other stars but have such lousy low-resolution images of ones in the Solar System ?

Sorry, what ?

5) Is there sound in space ?

This one is actually more complicated than Randall Munroe gives credit for, simply stating it in the "weird (and worrying) questions from the inbox" section of his otherwise excellent What If ? book without actually answering it. Here I correct this oversight, because the answer is a definite maybe.

Follow the reluctant adventures in the life of a Welsh astrophysicist sent around the world for some reason, wherein I photograph potatoes and destroy galaxies in the name of science. And don't forget about my website, www.rhysy.net

Sunday, 12 February 2017

Thursday, 2 February 2017

On Bias

Some words are well-known for meaning different things to scientists and the general public. "Theory" is supposedly one of those, "skeptical" is another. The reality is that even within science, these words are used in a multitude of different ways that's often context dependent. If I say to my colleagues, "it's only a theory", they will not shout at me for deriding the value of a hard-won scientific discovery - that is a purely fictitious idea manufactured by the internet. It's true that theory does have that special meaning, but it isn't used this way with any special rigour or even any rigour at all. Indeed, "theorist" is routinely used as a term for anyone who spends more time on ideas than observations, not someone who continuously constructs amazingly well-tested models.

"Bias" is a bit different. The common meaning is something like an unintended, unreasonable preference : "you're only being mean to my pet tortoise because he bit you once !". And indeed, if said tortoise hardly ever bites anyone, it wouldn't be reasonable to avoid them forever. But in science, a bias can not only be a good thing, it can be essential.

Science is biased ! Oh noes !

Suppose you wanted to discover a tortoises' favourite food. Well, that's easy, you just take your friend's tortoise, plonk down a load of stuff he likes to eat down and... no. That answer isn't even wrong, because the question was silly. You need to be more specific. Try : of all the available food in the house, what does Tim the tortoise like to eat best ? That question you can answer. Determining Tim's favourite food would, technically, involve Tim sampling every food on the planet - but limiting it to what's currently available is a solvable problem.

Which is no excuse to be an areshole whenever someone says their favourite food is "blah", because you bloody well know what favourite means in this context. Or at least you should. I had a friend who was annoyed whenever people said they didn't like rap music, as though they'd listened to all rap music. Which was a very unfair assumption. Obviously a) the statement usually just means, "I don't like all the rap music I've ever heard but it's self-evident that I can't really judge music I haven't heard, duuuuh !" and b) if there's something intrinsic about the style of monotone talking over music that annoys you, chances are you're not gonna like any rap music. Your inference that you don't like any and all rap music may not be 100% iron-clad certainty, but it's a perfectly reasonable extrapolation for everyday life. You're not "biased" against it, you genuinely don't like it.

But suppose you did want to discover the favourite food of the tortoise. Not just Tim but the general preference of all tortoises. OK, let's make this easier and restrict it to, say, the Magnificent Eurasian Tortoise, found all across Europe and Asia and known for its golden carapace and acute financial acumen. Now, if you wanted to find the favourite food of the tortoise in the wild, how should you choose a sample of tortoises to examine ? Should you look only at those in Europe which are easiest to catch ? Should you instead look at the more active tortoises of the Asian steppe, which can run away at tremendous speed and therefore eat more ? Should you only look at very young or old tortoises or a mixture of the two ?

| And should you limit your selection to tortoises with rocket packs ? |

The more specific your question, the more meaningful your answer. There might not be a favourite food of the species as a whole because its geographic distribution is so large - different tortoises eat different things depending on what's available. But tortoises might, conceivably, have subtle differences such that Asian tortoises genuinely prefer different foods to the European ones. You'd have to give them both samples of the other's food. And you'd have to try it with hatchlings and raise them over many decades then try swapping their food, to be sure they just hadn't got used to some foods in order to tell if it was really an innate, genetic difference or not. Complicated, isn't it ?

So what you do is deliberately bias your question and your sample to get a meaningful answer. You abandon your mad obsession with finding out what tortoises really like to eat and instead limit yourself to determining what they do eat in specific geographical regions at different ages. So you monitor a large sample of tortoises across Europe and Asia and record as much information about them as you can. Afterwards, you split your sample based on things like location, age, gender, and weight, and compare what they actually do eat with what they potentially could eat in each region. Only then can you begin to say useful (?) things like, "young tortoises in Europe mostly eat lettuce whereas those in Asia tend to prefer cabbage, but old tortoises all love carrots regardless of age, location or any other factor".

Had you gone charging in without any of this, you might have just picked a representative sample of tortoises - that is, one that consists of tortoises of all different sizes, ages and genders in roughly the same proportion as in the total population - and said something daft like, "the Magnificent Eurasian Tortoise's favourite food is cabbage." That might be the case overall if the whole population consists mainly of Asian tortoises of a certain age, say - in this case your "representative" sample is actually biased. You, in your thoughtless stupidity, have failed to account for the subtleties of statistical analysis.

The trick to getting a meaningful answer is not to eliminate bias, but to ask a specific question and bias the sample appropriately. It's very much easier to address, "what's the favourite food of young European tortoises ?" because you know exactly what sample you need; a representative sample of the entire tortoise population would give you completely the wrong answer. Bias can be essential.

Scientific bias can also be purely accidental. If didn't go and measure the tortoises yourself but were just given the raw data, you might choose to analyse a sample that inadvertently contained a bias you wouldn't have anticipated. For example if you were interested in what made tortoises obese you might select the fattest 10%, say. But if they all happened to come from the same geographical area, there might be a unique factor at work - so you'd never work out the true cause of tortoise obesity in most cases.

For these reasons, scientific bias is sometimes referred to as a selection bias or selection effect. It isn't necessarily good or bad and doesn't imply the researcher screwed up or wants to prove their pet theory. Those sorts of bias do happen in science, obviously, and that's what most people mean by bias in everyday conversation.

Everyday bias

Bias and discrimination isn't always unfair. Giving the job to the best people may be biased towards the most educated or the physically strongest, but that's hardly unfair if you're looking for someone skilled in advanced mathematics or a manual labourer. What would be unfair is not giving everyone the same opportunities to pursue those careers in the first place - to say, "no, you're ginger, you can't learn maths." Discriminating on merit is fine as long as everyone's had a chance to compete fairly.

Then there are cases where even an unfair bias is perfectly understandable. Of course people will be surprised if a 100 year old competes in a marathon and no-one would expect them to win. Ostensibly you could just let them enter and wait and see what would happen, but the link between fitness and age is so well-established that expecting them to win would be a little bit mad. You might even suggest, not unreasonably, that perhaps they should be subjected to medical checks you wouldn't ask of younger competitors, for their own safety. Would that really be unfair ? I don't know, but it's certainly a grey area (you probably wouldn't stop them actually competing, though, unless you found a good medical reason beyond "they're very old").

So you might also be forgiven for thinking that perhaps making regulations which restrict the movements of those more likely to commit crimes is understandable. And to some degree, it is. If you insist on shouting incredibly loudly about the crimes of one particular group while labelling them in a different way to the crimes of another - Muslims are "terrorists" whereas gun-nuts are "lone wolves" - then of course people are going to believe there's something different about that group. Especially if you essentially never bring up their religion except when denigrating them as terrorists, omitting that suddenly "irrelevant detail" when they make the news for other reasons. Legitimate, entirely politically correct criticism of individuals so easily transmutes into a witch hunt.

Here the bias of the media is abundantly evident. There's no good statistical reason to fear Muslim "terrorism" over any other kind of homicide, and indeed in the USA (see figure below) this is positively deranged. Now, at this point one may say, "but Muslim culture blah blah blah" or, "the Koran says blah blah blah", as people often do. OK. That's absolutely fine, but it's a completely different topic to whether or not one group is measurably safer than another. If you want to talk about preventing terrorism, there can't be any debate about that. In America you're far more likely to be shot but a non-Muslim nutcase; in Europe it's true that most recent terror attacks have been caused by Islamic extremists... but the number of dangerous extremists is such an insanely tiny fraction of the community it makes no sense to be scared of them as compared to any other ethnic or religious group. So I can understand why you'd be concerned, but that doesn't mean you're not just flat-out wrong.

For a final example let's look at the recent "Muslim ban" from a different perspective : not whether the ban is right or wrong, but how supporters and detractors view each other. In my opinion, the continuous depiction of the other side as "biased", as though at inevitably means they're just wrong and untrustworthy, is one of the most dangerous tools in political debate. As we've seen, being biased doesn't always mean you're wrong - so long as you understand that bias. But is there an unfair perspective at work here ? Is one side resorting to double standards, engaging in mass hysteria because Trump instigated a ban but completely ignoring Obama's earlier, similar restrictions ?

Let's make two simplifying assumptions here just for the sake of argument. Let's suppose, in defiance of the actual facts, that there was a good reason to be suspicious of Muslims but the case wasn't yet proven. Let's also suppose that Obama and Trump's bans were identical and explicitly targeted at Muslims, which is also factually wrong. Don't worry, well return to the actual bans shortly.

If you were to say, "President Obama's Muslim ban was bad because Obama is a bad person, but Trump's ban is good because Trump is a great man and he can do no wrong", then you are irredeemably biased and unprincipled. You are supporting a policy not based on that policy itself but on who enacts it. If, however, you were to say, "I support Obama overall, but the Muslim ban was an inexcusable failure. I campaigned against it and will do the same against Trump's ban." then you are not biased. You are judging the policy based on the policy itself, and while you may still be an Obama supporter you aren't trying to excuse one particular action you don't like.

The flip side of this is that you could be unbiased on the other side. You could say, "I didn't vote for Obama but I supported his Muslim ban because it was the right thing to do, and I support Trump in part because of this policy". That's not biased or unprincipled either. I personally wouldn't support your principles in this case, and would in fact strongly object to them, but I will acknowledge that you have them.

It's also important to recognise that there can be degrees of bias. You could say, "I think Obama is just trying to do the right thing and though this ban is a failure of principle, this might be a time when unusual measures are required." In this case you've partially abandoned your principles for the sake of the man : you're prepared to support a policy that you don't really approve of, but you're honest enough to admit that.

It's the difference between saying, "I support Trump so I support a ban on Muslims", and, "I support a ban on Muslims so that's why Trump has my support". The former is biased, the latter principled - even if we might not like those principles.

aren't quite like these simplifying assumptions. For starters it's apparently not a Muslim ban; while technically true this is a clear example of political bullshit since that's how it was unambiguously described in the election campaign. The bans also differ in their scale and execution : the Obama administration's limited to a single country versus Trump's seven (as opposed to the previous which visa waivers from seven countries were made more difficult to obtain, which is not the same as a ban at all); Trump's including green card holders who were already extensively checked for eligibility to reside in the US, but now, at the stroke of a pen, excluded.

But the crucial difference is the preliminary rhetoric to the ban. Obama never made a ban on Muslims a major part of his campaign policy, and was in fact well-known for speaking out against discrimination. He also didn't institute the ban as an executive order either, though he did fail to veto it. Only the most extreme Obamaphiles would attempt to defend the Obama ban while decrying Trump's; the rest of us should see it as a failure.

But what was seen as a failure of the old administration is being touted as a triumph of the new - Trump didn't merely allow the ban, he encouraged it, enacted it as an executive order, and promoted it with discriminatory rhetoric. So it is wholly unfair to accuse all but the most extreme liberals of bias or double standards here - of course people are going to react differently when discrimination is promoted as a success rather than (at most) an excusable failure. Compared to this, even the important difference of Trump's ban affecting green card holders looks relatively minor, as does its shoddy execution.

So no, it's not fair to accuse the left of bias against Trump in this case. First, the need for the ban is flatly contradicted by the facts - and there's nothing the slightest bit unfair about being biased towards the facts. That's a case of perfectly sensible bias, as we saw happens all the time in scientific analysis. Second, the bans were different in scale, execution, and most importantly of all in stated intent. The latter turns the issue from one of "things I don't like" into "things I'm morally opposed to" - and few would deny anyone the right to protest over things they have moral objections to.

Conclusion

|

| We're not all just grumpy for no reason. |

Outside science bias has much more negative connotations, as though the other researcher suspected you of sampling the data in a way designed to deliberately mislead. Or that you only try and defend something or someone because of some pre-existing preference : a prejudice. Currently the political scene feels like little more than each party and its supporters accusing the other of "bias" (and its next of kin, "double standards") no matter what the situation.

This is dangerous. We're no longer looking at why people don't like the opposite position, we simply assume that because they don't like it they must be wrong. Brexiteers seem to fall victim to this like no other. Not a single one has presented me with a credible argument for leaving : they just go and say, "you don't get to ignore the vote result just because you don't like it", as though I had no actual reasons for not liking it at all. Yes, I prefer one argument to another. I am not impartial. That does not automatically equate to me being "biased", in the unfair sense, or being wrong, because you can damn well be biased for and against the facts. We've degenerated into endless bias wars, never really attacking the actual arguments at all. So I like to remember a useful quote :

Ironically enough, I can't stand Richard Dawkins. I guess I must be biased.

Tuesday, 31 January 2017

Be Careful What You Wish For

The current political crisis teeters on the brink of catastrophe. Never mind why Donald Drumpf won the election or why Brexit came to the fore from a fringe idea espoused only by a silly man who looks an awful lot like a toad, sometimes the how is more important.

Post-truth, a.k.a. bullshit, played a huge role in both of these political disasters, and may well yet play an equally huge role in translating them into physical disasters. Politicians have always been skilled liars and post-truth is nothing new, but the scale of it, the sheer brazen outrageousness of it - these were what caught everyone by surprise. The idea that a talking racist toupee could even win a single vote for the position nominally deemed to be leader of the free world is one so appallingly stupid that the very notion still seems impossible to countenance, let alone accept as grim and bitter reality.

As with any system under crisis, there are two challenges facing the political world at the moment. The first is to bring itself back from the brink of the abyss and prevent a slide into true chaos. The second is to reform and remake itself such that situations like this cannot happen again.

One proposed solution, probably the most obvious one of all, is that we need better politicians. And of course, we do. We need politicians who will not kowtow to populism and the braying of the mob without first trying to understand what is the mob actually needs as well as wants. We need politicians who are not afraid of the truth even when those truths go against our ideologies and dreams, who might nonetheless spin appealing, inspiring narratives but will admit when those narratives fail because there are whopping great facts in the way.

|

| But feel free to opt for the alternative fact that the boulder isn't there and just drive on regardless. I'm sure that'll work. |

Well, yes - in the short term. Such a move might well avert the current crisis, but by itself, without any other underlying changes to the political system, it will most assuredly lurch the entire creaking edifice into the next and far greater calamity - a political singularity beyond which no-one can reasonably say precisely what disasters may befall us, but which we may be confident will be very real, physical catastrophes and not merely problems for the 1%. Because the problem isn't just with the politicians. It's a threefold problem, and without addressing each aspect of it, we are forever doomed to more of the same.

First, there are the politicians themselves. If you have bad rulers the rest is irrelevant. Second is the political system in which those rulers operate. No matter how noble their intentions, if the system of government is itself fundamentally flawed, the politician's aspirations will be rendered impotent or perverted. And third, assuming that we wish to maintain some form of democracy, are the voters themselves. No matter the greatness of the politicians or the suitability of the system of governance, if the voters are a bunch of bigoted idiots, a fair and just society will not result.

So what will happen if we elect a bunch of scientists into the current political systems without changing that system or regard for the will of the voters ? The road to hell is indeed paved with good intentions...

In the short term, we might - might - see some improvements and cause for hope. We may see policies based on evidence and facts, not feelings and ideologies. We may get, for example, compulsory vaccinations, investment in renewable energy, a decline in fossil fuels, the development of a space industry, and increased freedom of movement. But we may not, and in the long-term any gains will surely be undone. Because the current ruling system is at best influenced by facts, but it is certainly not dependent on them and can often freely ignore them altogether. Failure to account for the irrational nature of the system and the voters will bring disaster, because successful politics depends far less on how the world really is and far more on how the voters wish or believe it to be.

There are at least three reasons why this modern variant of philosopher kings will ultimately fail and fail hard.

1) The political system is partisan and not very nice about it

The first is that both the political system and (to varying degrees) the politicians themselves are inherently partisan and it is strongly in the interests of everyone involved to maintain that partisanship. The system of opposing (albeit occasionally collaborating) political parties is one that demands enemies, those who are seen as attacking the others not because the facts support their own claims but because it's their political duty to do so. Let's not forget the strength of this system as well as highlighting its weaknesses : the government is continually held to account by the opposition. But post-truth happens in part because (to a sufficient extent) it genuinely does not matter for a politician what the truth is, because that does not necessarily correlate with them winning elections. And so it behooves the partisan politician to create enemies where none exist.

You cannot enter the current system and avoid being seen as partisan. The tribal nature of the system simply does not permit it. Like a fly caught in a web, one may struggle valiantly for a while, but ultimately the only choices are to escape entirely or fall victim to the spider in the centre. Now, this actually works quite well most of the time, because politics is largely about interpretation, prediction, and opinion. And it's fundamentally good to debate those and to present opposing views. Debating "alternative facts", however, is to make an enemy of the truth. And that is self-evidently stupid.

Such things already happen when there's even a mere whiff of foul politics associated with scientific findings. Global warming is now seen by its detractors, bizarrely, as a left-wing conspiracy. Those claiming that nuclear power and genetically modified organisms are safe are seen as corporate tools. Scientists themselves are all too often derided as "liberal elites", as though that were insulting. Now, it is true that this is not always the case, and that experts are still (whatever Michael Gove may wish) widely regarded as far more trustworthy than politicians. Nevertheless, expert advice is often ignored, and while the mistrust of science is as yet very far from complete, all this has been achieved while science is truly apolitical.

So consider for a moment what those with subjective bias might accomplish if scientists actually participated in the political system directly and in large numbers. To discredit them as biased, partisan members of the tribal opposition would become a thousandfold easier. This will happen not (only) because politicians are innately scheming self-interested power-hungry maniacs, but because the system they work in demands it of their profession.

This rampant cynicism needs tempering, however, because it's not quite so awful. Remember, there are good reasons the political system is the way it is - the need to present voters with a choice, to hold the government to account for its actions - just as there are very good reasons the scientific system has evolved into something infinitely less partisan. But no reform of the political process can possibly succeed without acknowledging the underlying nature of the system.

But, as I said, it's not quite so awful. I said that the truth genuinely does not matter to a politician, but of course this is only true to some degree. There are those who maintain their basic decency despite the pressures of the system. But more fundamentally, scientists currently possess the awesome power of being able to hold politicians to account. Their knowledge is and is seen to be politically independent. It is objective and derived for knowledge's sake. Thus, while it is hardly fair to paint all politicians as the vacuous, self-serving tools of the system I have described, even those that are cannot fool all of the people all of the time. Scientific knowledge acts as part of a series of critical checks and balances of the system : even the worst politicians are bound to respect the truth at least a little. Political reality is not wholly detached from objective reality so long as we have a fair idea of what the hell objective reality actually is.

Now consider what would happen if there were no perceived boundaries between knowledge and politics. Post-truth and alternative facts would be only the beginning, and this is a chilling prospect which should terrify anyone.

2) Scientists are people too

The second reason is that scientists are not saints. Once you start depicting people as your enemy, they very often become your enemy. While the rough-and-tumble world of academia has its feuds and rivalries, it seldom degenerates into the acrimonious, public and bitterly personal attacks that are a mainstay of political life. Nor is it particularly duplicitous - scientists tend to do science because they want to do science, not pursue fortune and glory. Get caught lying as a politician and it's not even a scandal. Get caught lying as a scientist and your career can be ruined.

Scientists are ill-equipped to deal with political reality not because they're particularly thin-skinned precious little snowflakes, but because no-one deals well when transitioning to a radically different social environment. The cool detachment and playful exploration requisite of science has hardly a place in the political arena. To expect scientists to maintain their objectivity in the face of such an onslaught is not reasonable : they will lose their objectivity. They will become partisan, not because they are bad people but because, like the politicians before them, they are people. And because the system demands it, so long as they want to stay in office.

And worse, science risks the danger of itself becoming a political movement. If that happens, then all is lost, and that's not hyperbole. There will be no objective facts to hold politicians to account, because all will be determined by political motivations. Science as a political movement is a glass ceiling : science's power and influence in the political sphere comes from its trusted nature; it is above politics. Blur the lines of politics and science and glass ceiling will break. The very thing that makes science valuable in politics, its power to hold politicians to account, will be gone. There will be no checks on the facts because no-one will believe the facts. The tribalism that's currently such a leading source of mistrust of science will run rampant. Instead of reaching out and persuading the most important people of all - those who think science is all some kind of fairy story - they will be driven further away and their voices will become very much louder. It is those who deny the findings of science that we should be trying to reach, not engage in endless chest-thumping exercises.

And it may be even far worse and darker than that. Currently, scientists possess knowledge and a somewhat mediocre level of influence. Now suppose they are given the abilities to make laws and run the country. Who, then, will hold the philosopher kings to account ? No-one. And that is far, far too much power to give to any group - again, not because they are bad people, but because they are people.

One may object at this point for a number of reasons. Science is above politics, one may say, but scientists aren't. They cannot be. They have the same rights and responsibilities as anyone else to promote their cause and call out injustice where they see it, and nor should they be denied the right to participate as fully in the political process as anyone else : voting, joining activist groups, protesting, writing blogs, etc.; being a scientists is not an excuse to avoid making difficult moral choices. And a few scientists becoming politicians, even leading political figures (especially in certain ministerial positions), will certainly not bring about the End of Days. Rather, it's an issue of responsibility. Scientists joining the system en masse, or as a slow but steady trickle, risks science itself becoming or being perceived as a partisan political movement. If that happens, its whole usefulness to society would be at an end.

3) Have you ever seen what happens to scientists when they become managers ? Cos I have

Another objection that one may raise is that by changing the politicians to people who are fundamentally more interested in the truth than winning votes, the very system of politics itself may change. But again, scientists are not saints. There's no indication that people who've dedicated their lives to physics or biology or chemistry would be especially suited to understand, let alone reform, the political system in a coherent and sensible way. Or that they would have any special insight into how to create a new one from the bottom-up. The philosopher kings of Plato's Republic were not selected on the basis of their skill at critical analysis, but on their skill of ruling.

There's nothing about studying the natural world that either attracts those with a special ability to understand human psychology, nor does it bestow that ability. There's a very good reason most scientists choose a scientific career instead of one in politics, and from my experience I have very little faith that a hitherto untapped reservoir of psychological and political brilliance is lurking amongst my colleagues. They are fundamentally different skill sets from scientific analysis. And so the third reason philosopher kings will fail is that scientists are neither trained nor especially well-suited to leadership or rhetoric; they are very ill-equipped either to reform the political system or inspire the voters. This is a key point I've had to explain to my colleagues many times : in politics you have to be able to inspire and persuade people, to carry them with you - you cannot just act against their will.

So we should just give up ?

|

| Everybody PANIC !!!! |

Let's consider an absurdly extreme example. Absurd extremes need to be handled with care as they are often misleading compared to the complexities of the real world (e.g. the notorious trolley problem) - but they sometimes help elucidate our thought processes and highlight important aspects of certain situations, even if they have numerous flaws of detail.

So bearing that in mind, let's suppose that voters were given the choice between, say, Boris Johnson and Smaug the dragon. Now, I know many of you hate Boris rather a lot. That's absolutely fine. But he's not going to actually burn everyone alive and eat them, so if you vote for Smaug you are simply insane. It wasn't a great choice, no, but one option was clearly and massively better than the others. Sometimes there aren't any good choices, but you still have to choose.

This particular absurd example is better than most, as it's not so very far from recent real-world examples and it illustrates nicely the trifold problem : the lousy system that led the stupid voters to choosing a terrible ruler. If you want the voters to make better choices, you not only have to give them better options but you also have to ensure that they're capable of at least rudimentary decision-making and at least trying to be objective. Responsibility for the outcome of vote is shared three ways. You don't have to make everyone a genius, nor do you have to give them figures of the calibre of Gandhi and Lincoln. You just need a system where a motherfrakin' dragon isn't allowed on the ballot and the voters wouldn't vote in significant numbers for him if he was.

This is not easy. In fact it is extraordinarily difficult, because while there are only three components to the body politic that we need to consider here, the links between them are far more complex - each is like a multi-headed hydra. So in practise, achieving reform of these three aspects means a lot more than changing politicians, the electoral system and how voters are appeased. In order to get something approaching a reasonable system where Smaug couldn't ever win, no matter how brilliant his campaign strategy (fire-breathing and sinister threats notwithstanding), far more fundamental changes with far-reaching implications are needed. It would be nice if we could simply elect the right people and then everything will get better. But this is not the case, and wishing for a thing does not make it so.

Building Better Worlds

I will not rant on here at length about how I would choose to construct a Brave New World (enthusiasts should read this). However, I will briefly mention two parts of the system that, in my view, are particularly weak links that if we reformed properly would go a long way towards a better politics. What I'm particularly concerned about is how parliaments communicate to their voters and how those voters assess the information presented to them. Solve these issues, I think, and reforms needed to the parliamentary system (for all the problems of partisan politics I've described) will be relatively minor.

1) The Media

I've talked about this before; John Oliver has also done an excellent piece on clickbaiting. Scientist and journalist are in full agreement, good. The media are a particularly important nerve in the body politic because they convey information to and fro between rulers and ruled, not only directly but also regarding the ruling system as well as on the facts and findings of other apolitical systems. This gives them tremendous influence in society, offering them, for instance, the opportunity to bear-bait the mob when the legitimate, independent judiciary throws a spanner in governmental plans... or indeed to provoke dissent when the government exceeds its legal authority.

The media's power is vast, and it can be an important force for justice... but it desperately needs regulation and responsibility. Freedom of speech has been taken to the absurd absolute of freedom of fraud, in part because of twisted ideologies and in part because of the simple need to make a sale. I will not presume here to determine precisely how the media should be run, I only want to point out that this problem exists. Even if politicians were truly pinnacles of integrity, this problem would still exist. And it's a big one. Change the business model, change the legal regulations... whatever you do, prevent the normalisation of incredibly biased news sources full of hate speech. I do not say ban newspapers from supporting political parties, but I do say that the number of media outlets any individual can control should be limited, and papers openly siding with political parties should not be the norm. But I digress.

2) Education, Education, Education

This second weak link is even more fundamental. If the majority of the media-purchasing public are able to properly evaluate reports and understand how they're being manipulated, misinformation and fake news would become very much harder to get away with. Readers would not desire it, ergo newspapers wouldn't sell it. Is this a pipe dream ? Well it's certainly not easy.

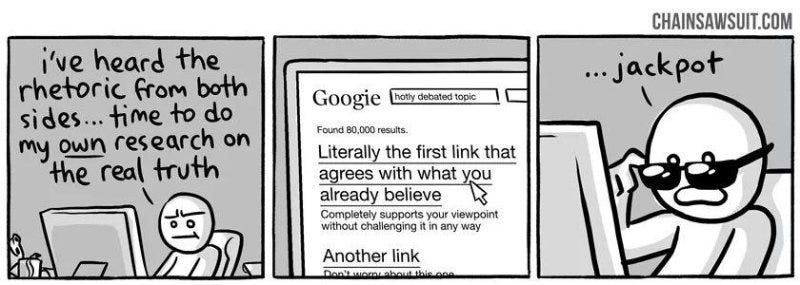

I've previously given examples of how this can be done, which on the surface don't seem all that difficult. Teach people about basic statistics so they understand the way numbers can be abused, to think about the wider context in which every piece of information fits, and not to leap to conclusions. Teach them to understand or at least search for the deeper meaning in complex literature so they won't take everything at face value. Use real-world examples of adverts to show them directly how they're being manipulated; compare headlines from different sources on the same story to give them different perspectives. Get students to debate with each other and get them to empathise with opposing points of view. Teach them about how science arrived at its conclusions and not just what those conclusions are. Try to get them to honestly understand how they themselves came to their own opinions. Teach them about self-examination and bias extensively, because so many people seem to think that anyone holding an opposing viewpoint must be biased, as though that automatically made them wrong and excused the need for any sort of actual debate.

The idea of citizenship lessons is also floated around from time to time. I'd be in favour of some version of these : earlier calls (I think it was Gordon Brown) for teaching "British values" struck me as nothing more than propaganda, however, the latest incarnation may be a much better idea. Teach people how laws are enabled - the complexities of the process, what the government can and can't do without consulting parliament or the people, exactly what "free speech" really means legally (because an awful lot of people really don't seem to understand this at all). Teaching them what their civil rights are and how government works is hardly propaganda, and might just help them understand the real difference between legitimate protest and sour grapes.

Teaching these things is easy, just as teaching facts is easy. The difficulty is that remembering facts is easy - remembering how to apply modes of thinking is not. This is why I advocate more emphasis on these methods in the humanities classes rather than the sciences, because to most people examining the news is far more relatable than examining how a rocket works. It wouldn't hurt to teach children these things in a way that's practical to their own lives either, because there's not a lot you can do about politics when you're too young to vote.

More importantly than what is taught is not so much how it's being taught as who is teaching. A good teacher can make any lesson interesting, but such people are few and far between. To inspire a genuine love of learning, and not simply to give children tools to win arguments about cats with strangers on the internet, is going to necessitate making such people the norm rather than the exception. And these things have to continue throughout the full duration of compulsory education, regularly, not just in the occasional one-off lessons.

Conclusions

I understand why you'd want more scientists in politics, but that would, at best, just be treating the symptom. The deeper underlying cause is that we have irrational rulers because we have an irrational society. All in all, it's remarkable that the partisan political system works as well as it does... but that's because it's designed to work with our human failings - to compensate for those who are more interested in winning the argument than in being right. Like any system, it has its limits. If the politicians never tell the truth about anything, it can't correct for that. But if they always tell the truth then it can't process this either, because it demands voters be given a choice when sometimes the facts do not permit one. The system takes the flawed, irrational nature of its participants as a given; it does not seek to change the nature of the beast.

So you can't elect scientists into the current system and expect things to improve. Rather the system and its existing incumbents will ensure that the newcomers are perceived as partisan and actually become partisan themselves. This removes a vital source of independent fact-checking, resulting in the loss of an essential check on the system that keeps it in its precarious balance. It will greatly exacerbate criticism of science and the critics will be justified, because science will no longer be about knowledge for knowledge's sake. Scientists care about integrity in part because the system in which they work is unlike the political system : it fosters and rewards that integrity. Scientists are not especially noble or virtuous creatures; you ask too much of them to remain objective in a system designed to burn away all objectivity.

That is why the usefulness of science is greatest when it remains beyond politics. Mix the two and both will suffer.

No, if you want to improve society, you must look at the wider issues. Most certainly it would be a good idea if the rulers acted based on reliable information. To do that we undoubtedly need educated rulers (though not necessarily experts) but also educated voters. Without the latter you won't elect sensible rulers - not ever. And when you do have educated voters electing sensible rulers, you'll need to change the governmental system, otherwise it will keep on doing what it's designed to do : making enemies. Except now it will be making an enemy of the truth.

Getting the electorate to be more rational obviously isn't easy. The reforms I've suggested to the media and the education system certainly won't lead to a Utopia or even a secure, stable system. At best they would have given the other sides the edge in the Brexit/Trump vote. Because even when people are well-educated and well-off, they don't necessarily act rationally. Trump voters were not particularly impoverished or poorly educated. Tory voters include the very wealthy with (supposedly) literally the best education money can by - but for some people it's not enough to be on top, they must also squash those at the bottom. Others - seemingly intelligent people - even sincerely believe that their policies that hurt the less fortunate or discriminate against foreigners are genuinely morally good.

It is absolutely essential to recognise the strength of the inherent irrational nature of the human condition, even if it's impossible to fully apprehend it. This is why you cannot simply give people more information or more rational leaders and expect to get a more rational society as a result; ideologies are not so lightly thrown aside. Which is why the fight for rational thought must, ironically, be a battle for hearts as well as minds. And it must be fought in the classrooms from nursery school upwards, not just by teaching science and maths but in all aspects of education, as a core, guiding principle of the entire system.

The naive say that changing but a single aspect of the body politic - the rulers, the ruled, or the ruling system - is sufficient to remake the world or will itself bring about reform of the other factors. The cynic understands that this is not so, but believes that change is impossible - that you cannot change the nature of the beast. Those standing in the middle ground say that only without attempting change is change certainly impossible. For if we cannot achieve a true Nirvana, a paradise free of violence and suffering of all kinds, perhaps we can yet build a world free of the worst aspects of ourselves. A world in which the petty, the spiteful, the hateful Trumps and Hitlers and Farages cannot exploit the violence and fear of the voters, but are themselves terrified of it.

Sunday, 29 January 2017

Ask An Astronomer Anything At All About Astronomy (XXXI)

The first AAAAAAAA of 2017 ! Well not really, because most of the world is in a state of panic right now so screaming loudly is an understandable response. It's the first batch of astronomy questions here though, and at the rate things are going it might be the last. Still, with about 275 answered to date, maybe there'll be time to make it to the big 300...

Since it's been a good long while since I did one of these, here's a reminder to new readers that the actual answers to the questions are in the links. It's not just me being snarky.

1) How fast could an Orion drive spaceship get to Mars ?

Not as fast as your mum.

2) Do all astronomical instruments have the same contrast range ?

No.

3) Could frame dragging account for recent observations explaining away dark matter ?

No.

4) What would happen if dark matter started absorbing light ?

All the lights would go out and kittens would explode.

5) What could we do to detect dark matter if we had infinite energy and resources ?

EVERYTHING. It would involve a lot of cackling.

6) What about this press release on ram pressure stripping being due to dark matter ?

It's wrong.

7) Once all the stars go out, will all the hot gas around galaxies start collapsing and form more stars ?

Eventually yes. We'll be dead by then though.

8) Could there be dark matter halos which are really just normal matter that's not doing anything ?

No.

9) Do most models of dark matter have it as self-interacting ?

Nah.

10) Would you consider Callisto and Hyperion to be planets if they were orbiting the Sun ?

Callisto yes, Hyperion no.

11) Would self-interacting dark matter be just like a gas ?

No.

Since it's been a good long while since I did one of these, here's a reminder to new readers that the actual answers to the questions are in the links. It's not just me being snarky.

1) How fast could an Orion drive spaceship get to Mars ?

Not as fast as your mum.

2) Do all astronomical instruments have the same contrast range ?

No.

3) Could frame dragging account for recent observations explaining away dark matter ?

No.

4) What would happen if dark matter started absorbing light ?

All the lights would go out and kittens would explode.

5) What could we do to detect dark matter if we had infinite energy and resources ?

EVERYTHING. It would involve a lot of cackling.

6) What about this press release on ram pressure stripping being due to dark matter ?

It's wrong.

7) Once all the stars go out, will all the hot gas around galaxies start collapsing and form more stars ?

Eventually yes. We'll be dead by then though.

8) Could there be dark matter halos which are really just normal matter that's not doing anything ?

No.

9) Do most models of dark matter have it as self-interacting ?

Nah.

10) Would you consider Callisto and Hyperion to be planets if they were orbiting the Sun ?

Callisto yes, Hyperion no.

11) Would self-interacting dark matter be just like a gas ?

No.

Sunday, 22 January 2017

Check Out My Kinky Curves

As usual, I'm following up my latest paper with a human-readable blog post. In this one I examine yet again why some clouds of gas in the Virgo cluster might be starless "dark galaxies" and how we can distinguish them from gas clouds ripped out of normal galaxies during close encounters. I also explore just why it's seriously crazily unlikely that some clouds are just interaction debris, with the help of several dogs and a lot of long kinky streams.

What are these "galaxy" thingies, anyway ?

Galaxies come in all shapes and sizes. Some are spectacular....

...while others are deadly dull.

Both of these images mainly show you the stars. You can also see some of their gas and dust, but not all, because gas and dust shine at different wavelengths than you can see with an ordinary telescope. What you can't see at all is the dark matter. The reason we think dark matter is there is from looking at the motions of the stars and gas - they're going too fast to be held together by their own mass, so there must* be something else holding them together that we can't see.

* I'm simplifying massively here, in an effort to keep this post shorter than War & Peace.

From the measurements, dark matter typically makes up 90% of the mass of a galaxy. There's far more dark matter than normal matter in the Universe. To the dark matter, stars are unimportant. If every star in the galaxy exploded, the dark matter cloud (or "halo") holding them in their orbits wouldn't notice. So could there be "dark galaxies" in the Universe made entirely of dark matter ?

Well, maybe. If they did exist they'd solve a major problem in astrophysics : cosmological models get the structure of the Universe right, but they predict around ten times as many galaxies as observed (most of these "missing galaxies" should be small companions of larger galaxies). If most of these didn't contain stars that would solve the problem pretty neatly.

Real dark galaxies wouldn't need some terrifying stellar Armageddon to explain why they're dark. It could be that some dark halos just never accumulated enough gas to from any stars (or at least too few for us to detect), or the first supernovae may have blasted all the gas out and prevented further star formation. So there are at least vaguely-plausible reasons why these things both should and could exist.

But do they ? Perhaps. If they contain no gas and stars at all then they'd be bloody hard to find, but it's possible they have just a little bit of gas - enough for us to detect, but not so much that they'd form (m)any stars. They'd be discs of gas rotating just like normal galaxies, but optically dark. The only way to see them would be with a radio telescope, which can detect the gas from its own emission.

Do dark galaxies really exist or are you just making this up because galaxies without stars is just a bloody daft idea

Actually, over the years quite a few candidate dark galaxies have been detected. The ones I'm most interested in are - because of my massive ego, obviously - the ones I found in my thesis project, a survey of the Virgo cluster. They seem to fit the bill pretty well : they (apparently) rotate as quickly as massive galaxies (about 100 km/s) but they have just a little bit of gas and no stars whatsoever - nothing else. The only way they could avoid flying apart is if they were embedded in dark matter halos, because their detectable gas mass is very small while their rotation speed is very fast. I'll call them the AGES clouds from here on in, since they were found with the Arecibo Galaxy Environment Survey.

So what's the problem ? If they were far away from any other galaxies, it would be very tempting to declare Game Over - dark galaxies found, cosmology problem solved, tea and biscuits for all, huzzah ! But they're not so isolated. A galaxy cluster is a realm of chaos, with thousands of galaxies flying past each other like bees on crack. These encounters can rip gas out of galaxies and leave bits of hydrogen fluff lying around all over the place.

It's possible that some or all of these dark hydrogen clouds are just "tidal debris" from galaxy interactions, with the messy encounters creating the illusion of rotation. We don't really measure rotation directly, just how fast the material is moving along our line of sight. Unfortunately our observations aren't very high resolution - we only get one pixel per cloud*. So we don't know how big the gas clouds are either, just their maximum size.

*When we have higher resolution observations of normal galaxies, we invariably find that this "velocity width" measurement really does correspond to rotation.

Previous papers have claimed that it's entirely possible to produce things that look like galaxies but are actually nothing of the sort. Instead of stable, long-lived rotating objects, they're actually short-lived objects in the process of disintegrating and we've just happened to catch them at a bad moment right before they fly apart.

Those results seem to hold pretty well for large objects. Unfortunately a lot of people seem to have read the older results and decided that they can also explain smaller ones. Regular readers will remember that we've previously found pretty strong evidence against that. It's easy to get a large change of velocity (that is, to fake the appearance of rotation) across a large feature, but much harder to get the same change across smaller ones. Specifically, it's damn near impossible to make objects as small as the AGES Virgo clouds with velocity widths anywhere near as high as their measured 100-200 km/s.

Are you really, really sure these clouds aren't just tidal debris ?

Our previous simulations dropped a long gas stream into a model of a galaxy cluster so we could watch the luckless thing get harassed into itty-bitty pieces by the cluster's gravity. This time we've gone one better and dropped a simulated galaxy into the cluster, so we can watch the stream's formation as well as what happens to the parent galaxy. Much more realistic (but technically harder to do and slower to compute, which is why we didn't do it originally).

Just like last time, we dropped our galaxy on a whole bunch of different trajectories (26) to make sure we didn't just happen to select one unusual path where the galaxy got obliterated or something daft like that. But we didn't just pick any-old galaxy to drop through the cluster, oh no. The target galaxy was modelled after this rather photogenic spiral :

And you might well think, "that galaxy is a bit funny-looking, why did you choose that one ?". And you'd be right - that prominent spiral arm is rather unusual. It's an even more peculiar galaxy when you look at its gas. In fact, M99 is something of a celebrity in dark galaxy circles because there's a long gas stream coming off it, which contains the infamous VIRGOHI21 :

VIRGOHI21 is the densest part of the gas stream, and it's broadly similar to the other Virgo clouds (about the same gas mass and "rotation" speed) except for that long stream. So you might well now be convinced that NGC 4254 is a very weird galaxy indeed. Well, it is and it isn't. Its stars have a bit of a funny shape and it's got this weird gas stream. Even ignoring the gas stream, its gas disc is a bit lop-sided too, and it's very gas rich : in fact it has just about as much gas as a galaxy this size is ever likely to have.

And yet... it's not that odd. The overall distribution of stars is quite normal, as is the gas in the disc. It's a galaxy that got up on the wrong side of bed one morning and forgot to shower, not a total monstrous freak of nature that should have been killed at birth. Crucially, since it's got an awful lot of gas in the disc (and since that gas disc looks more-or-less normal), if you didn't know about the gas stream you'd never suspect it once had even more gas than it does now. If anything you'd wonder if maybe some interaction had given it extra gas, not ripped some of its gas away from it.

So there are two natural but mutually exclusive interpretations of NGC 4254 : it's pretty normal if you only consider its overall gas and star contents within the disc, or it's really weird if you look at its precise stellar distribution and the long gas stream. That's an interesting circle to square.

All this makes NGC 4254 a great target galaxy, which is why earlier studies used it as a target too. Our model starts off with an idealised version : we create smooth discs of gas and stars which have the same overall distribution, but don't reproduce the one-armed spiral. We also tried varying the gas content and distribution, as well as the mass of the dark matter since that's not so well-determined from the observations. Then we drop this into our galaxy cluster and see if the interactions reproduce any of those peculiar features, or things resembling the isolated clouds. Our cluster includes 400 other galaxies but only as simple point-masses : we don't model their gas and stars (that's far too computationally demanding), just their gravitational effects on the target.

So using M99 as our target may seem odd initially, but actually it lets us tackle several questions all at once :

1) Can we produce isolated gas clouds that look like dark galaxies by harassing a fairly normal spiral galaxy ?

2) What about fake dark galaxies in streams like VIRGOHI21 and the other strange features specific to the M99 system ?

3) Do the properties of the spiral galaxy make a big difference ?

Feel free to skip the next section if you want to get straight to the answers. Keep reading if it want to put these results in a bit more context.

Interlude : The Unnecessary Prequel

Time for a little backstory. One thing the referee and a slightly irate co-author made me tone down in the published paper was the criticism of the previous models. Originally the paper went into great detail about this, and while this was a bit excessive, I still would have preferred to state a few things more explicitly. Well, now I can ! And I will. Watch me.

Until we started re-investigating this, there were basically two explanations for the VIRGOHI21 system :

1) A simulation of Davies 2008 showed that if VIRGOHI21 was a giant dark galaxy, it could have created the stream largely from its own gas as it flew past M99. This could also explain the one prominent spiral arm. Unfortunately this model put VIRGOHI21 very much at the end of the gas stream, not in the middle as is actually the case. Bugger.

2) A simulation by Duc & Bournaud 2008 in which a normal galaxy tears gas out of M99, and VIRGOHI21 is just a kink in the stream rather than a dark galaxy. The "kink" is in the sense that the velocity of the gas changes very sharply as you go from the stream to VIRGOHI21 itself, rather than the stream suddenly changing direction.

But there are several problems with this second (much more popular) option. As mentioned, the gas content of M99 is pretty high, and its distribution is quite normal - which to my mind is strong evidence that the gas didn't come from M99, even without knowing what the true origin was. We can even quantify this, and although there isn't all that much gas in the stream, there's enough that if it had come from the spiral galaxy that would have made it truly exceptionally gas rich.

And yet long gas streams are very rare. So it's still entirely sensible to postulate that maybe this is indeed what happened : an unusually gas-rich galaxy had an encounter which tore off the gas into this long stream. An unusual explanation for an unusual object is not a daft idea by any means.

But VIRGOHI21 isn't just part of the stream which is a little bit denser than the rest : not only is it quite a lot denser, the velocity structure makes a very sharp "kink" - a sudden change, not a smooth one. Despite claims to the contrary, previous models actually have great difficulty reproducing this feature (more on that in a minute). They can make the long gas stream, sure, but not the feature that marked it out as weird in the first place. Long streams with smooth velocity changes are completely normal and therefore boring.

And the Duc model had other debatable points - nothing outrageous, but things that would be cause for concern. Their model of M99 had it being not only exceptionally gas rich (fair enough if you think the gas really did originate in the galaxy) but with a really weird gas distribution that's not at all typical of a spiral galaxy. They also gave it the absolute minimum amount of dark matter conceivable based on the observations of how fast the galaxy spins.

It's perfectly possible the target galaxy was weird. But this model has a weird galaxy also having a weird encounter, which makes it very unlikely indeed. A weird explanation for a weird object is fine... but don't forget, we also have those quite similar clouds from AGES. So, arguably, VIRGOHI21 isn't that unusual after all. And the conditions of the target galaxy in the Duc model made it so that it was as vulnerable to gas removal as possible - yet still the model did not reproduce the distinctive velocity kink.

Given all this, it seemed to be a good idea to re-visit the Duc model. Not precisely, because setting up a situation which could give a really good match to the M99/VIRGOHI21 system (as Duc did) is tricky and really another project. Instead, we wanted to see if features like that velocity kink (and the AGES clouds) would be more common using a galaxy like Duc's than our preferred "normal" version of M99.

Here I have to say that the referee, although otherwise a level-headed individual, did something I found quite irritating. In an earlier draft I had a (too) long paragraph quoting papers where people had seen the Duc results and decided (in no uncertain terms) that that meant, decisively, that all dark galaxy candidates could be explained as tidal debris. I pointed out in the paper that the success of one model does not preclude the success of others; the referee said this shouldn't be mentioned since any scientists should know this - despite the evidence of the papers where this was clearly not the case at all. Then in a later draft I pointed out the Davies model, which got the odd response that these new results "convincingly exclude" that hypothesis. That's a bit bizarre, because they most certainly don't do anything of the sort ! We didn't examine the Davies model in any way, so how can these results possible have any bearing on them ? Answer : they can't.

Without further ado, then, here's what the new results actually say.

So what happened ?

I expect you'd like to actually see some of the simulations, wouldn't you ? Well, here you go !

This isn't all of them, but visually they all look something like these. Have a look in the appendix if you want to see every one of the little buggers, but it's when you run the numbers you find out the interesting stuff.

1) Isolated clouds

The results were almost identical to our previous simulations. Isolated clouds up to the size of those seen in Virgo are really common in our simulations, but only at low velocity widths (< 50 km/s). They're pretty rare at higher widths (50 - 100 km/s) and utterly negligible at the high widths we're interested in (the real clouds are ~150 km/s). Harassment can certainly tear up a stream into itty-bitty pieces, but it does a lousy job of making it look like the ittiest-bittiest pieces are rotating. Works quite well for larger pieces, mind you.

2) Fake dark galaxies in streams

Maybe !

In fact our simulations reproduced the kinky velocity curves much better than the Duc model. The figure below compares the real VIRGOHI21, the Duc model, and ours.

Ours is clearly much kinkier than Duc's, though it's easy to understand why people might look at Duc's result and say, "sure, it's not quite kinky enough, but it's pretty close". I was expecting to have to come up with some way to measure exactly how kinky the streams were - thereby inventing a "kinkiness" parameter, but fortunately for me (and unfortunately for those with a sense of humour) this turned out to be unnecessary. Really kinky streams like the one on the right turned out to be so common there's not really any point in measuring them.

In some ways it's easy to see why our streams are so kinky (joke over, I promise) : we have 400 interacting galaxies, Duc had just two. But does this mean we can now explain VIRGOHI21 ? The referee thought so, despite my abject protestations. In fact I don't think we can. Our simulations were certainly kinky enough, but that's about it. They didn't reproduce that one prominent spiral arm, or the lop-sided gas disc, and again that model would require the galaxy to be really exceptionally gas rich. And the disparity between the gas and the stars, with that prominent spiral arm seen only in the distribution of stars and not the gas... well that's just odd.

OK, maybe that was the case. But the sharp kinks tend to be quite short-lived features, so what are the chances that we're seeing an intrinsically unusual galaxy during a very unusual phase of its evolution ? I don't know, but they're not high.

3) Does it matter what the galaxy was like ?

Sort of. OK, a lot. Well... not really. It depends what you're interested in.

We used three different initial galaxies : one is very similar to Duc's (lots of very extended gas and not so much dark matter), one is what we believe is the best match to the observations of M99, and the third is as massive as M99 can possibly be given the observational limits.

Using our standard model - which we believe is closest to the real M99 - we got a gas disc which remained pretty similar to the observations but sometimes had long gas streams pulled out of it. The gas distribution remained very similar to what it was like at the start, i.e. just like the observations.

Using our Duc-like model, which had less dark matter but more gas that was more extended, we got rather more gas stripping, as we'd expect. It tended to lose about the right amount of gas, so by the end the galaxy had about the same gas content as the real M99. But the distribution of gas was all wrong, and never resembled what we see in reality.

Both the standard and Duc-like models gave similar results for fake dark galaxies : kinky streams are very common, but isolated AGES-like clouds are rarer than an albino dodo.

Our most massive model was so massive it basically sat there like a lemon and didn't do anything. Sending it flying through 400 galaxies was like throwing peanuts at a rhinoceros.

Conclusions

We can also say that some features in hydrogen gas streams could well be just due to galaxy interactions - the appearance of rotation can be faked. But does this mean that VIRGOHI21 is itself now definitively not a dark galaxy after all ? Not by a long shot. The "kinky" interpretation doesn't explain all the features of the system, and the alternative hypothesis that it's a dark galaxy hasn't been explored in nearly as much detail. So it's still entirely possible that might do a better job of explaining where all that extra gas came from and why M99 is generally funny-looking. The success of one model does not preclude the success of another !

Likewise, while some clouds are almost certainly tidal debris, we can be equally confident that some are not. It's hardly a revelation that some clouds are debris - it would be positively bonkers to suggest otherwise - but what's more interesting is we can quantify which ones are probably debris and for which ones this explanation looks a bit silly. High velocity width features can be easily formed in streams but not in isolated clouds.

We can also answer why this is. Our simulations showed that clouds are always born in long streams. Small gas clouds are never torn out of galaxies directly. So the only way you can make a small isolated cloud is by ripping up a stream. But... high velocity width features are intrinsically more difficult to detect, so if you can detect something that's ~200 km/s wide you'll also be able to detect the lower-width rest of the stream as well, almost by definition. And high-width features are also the shortest lived, since they're flying apart. To disperse the rest of the stream while keeping the highest-width features as isolated clouds is bloody difficult : the dark galaxy hypothesis seems far more likely. And we already showed that dark galaxies could reproduce the observations very well in these cases.

The above points might make you question why we needed a simulation for this. In principle, yes, we could have deduced them from pure theory. But it's very much easier when you can actually watch it happen. Moreover, the model lets us quantify things far more precisely - especially the rate at which the clouds are produced, which can't be predicted without a simulation.

What's next ? Good news, everyone ! We have another 200 hours of Arecibo time awarded to do another survey area in Vrigo so with any luck we'll find more clouds. That will give us much better information about where they are in the cluster, if they're generally near to other galaxies and if their velocity widths are always so high. And we have 16 hours of time on the VLA to get better resolution observations, so we'll have a very much better idea of whether these things are rotating or not. Lastly, we have more simulations in preparation to test even more hypothesis about the origins and evolution of the clouds. It may take a while, but we'll get to the bottom of this eventually...

What are these "galaxy" thingies, anyway ?

Galaxies come in all shapes and sizes. Some are spectacular....

...while others are deadly dull.

Both of these images mainly show you the stars. You can also see some of their gas and dust, but not all, because gas and dust shine at different wavelengths than you can see with an ordinary telescope. What you can't see at all is the dark matter. The reason we think dark matter is there is from looking at the motions of the stars and gas - they're going too fast to be held together by their own mass, so there must* be something else holding them together that we can't see.

* I'm simplifying massively here, in an effort to keep this post shorter than War & Peace.

From the measurements, dark matter typically makes up 90% of the mass of a galaxy. There's far more dark matter than normal matter in the Universe. To the dark matter, stars are unimportant. If every star in the galaxy exploded, the dark matter cloud (or "halo") holding them in their orbits wouldn't notice. So could there be "dark galaxies" in the Universe made entirely of dark matter ?

| An old image of mine, symbolically depicting a dark galaxy against a galaxy cluster full of hot gas. In fact the standard models says that dark galaxies should be smooth, boring spheroids without nice spiral arms like in a proper galaxy. |

Real dark galaxies wouldn't need some terrifying stellar Armageddon to explain why they're dark. It could be that some dark halos just never accumulated enough gas to from any stars (or at least too few for us to detect), or the first supernovae may have blasted all the gas out and prevented further star formation. So there are at least vaguely-plausible reasons why these things both should and could exist.

But do they ? Perhaps. If they contain no gas and stars at all then they'd be bloody hard to find, but it's possible they have just a little bit of gas - enough for us to detect, but not so much that they'd form (m)any stars. They'd be discs of gas rotating just like normal galaxies, but optically dark. The only way to see them would be with a radio telescope, which can detect the gas from its own emission.

| It never hurts to remind people that a) radio telescopes make images, they generally do not "listen" to the sky; b) the sky would look completely different if we could see the neutral hydrogen gas in our Galaxy, as in the above example. |

Do dark galaxies really exist or are you just making this up because galaxies without stars is just a bloody daft idea

Actually, over the years quite a few candidate dark galaxies have been detected. The ones I'm most interested in are - because of my massive ego, obviously - the ones I found in my thesis project, a survey of the Virgo cluster. They seem to fit the bill pretty well : they (apparently) rotate as quickly as massive galaxies (about 100 km/s) but they have just a little bit of gas and no stars whatsoever - nothing else. The only way they could avoid flying apart is if they were embedded in dark matter halos, because their detectable gas mass is very small while their rotation speed is very fast. I'll call them the AGES clouds from here on in, since they were found with the Arecibo Galaxy Environment Survey.

So what's the problem ? If they were far away from any other galaxies, it would be very tempting to declare Game Over - dark galaxies found, cosmology problem solved, tea and biscuits for all, huzzah ! But they're not so isolated. A galaxy cluster is a realm of chaos, with thousands of galaxies flying past each other like bees on crack. These encounters can rip gas out of galaxies and leave bits of hydrogen fluff lying around all over the place.

|

| Dog owners will know what I'm talking about. |

*When we have higher resolution observations of normal galaxies, we invariably find that this "velocity width" measurement really does correspond to rotation.

Previous papers have claimed that it's entirely possible to produce things that look like galaxies but are actually nothing of the sort. Instead of stable, long-lived rotating objects, they're actually short-lived objects in the process of disintegrating and we've just happened to catch them at a bad moment right before they fly apart.

Those results seem to hold pretty well for large objects. Unfortunately a lot of people seem to have read the older results and decided that they can also explain smaller ones. Regular readers will remember that we've previously found pretty strong evidence against that. It's easy to get a large change of velocity (that is, to fake the appearance of rotation) across a large feature, but much harder to get the same change across smaller ones. Specifically, it's damn near impossible to make objects as small as the AGES Virgo clouds with velocity widths anywhere near as high as their measured 100-200 km/s.

Are you really, really sure these clouds aren't just tidal debris ?

Our previous simulations dropped a long gas stream into a model of a galaxy cluster so we could watch the luckless thing get harassed into itty-bitty pieces by the cluster's gravity. This time we've gone one better and dropped a simulated galaxy into the cluster, so we can watch the stream's formation as well as what happens to the parent galaxy. Much more realistic (but technically harder to do and slower to compute, which is why we didn't do it originally).

Just like last time, we dropped our galaxy on a whole bunch of different trajectories (26) to make sure we didn't just happen to select one unusual path where the galaxy got obliterated or something daft like that. But we didn't just pick any-old galaxy to drop through the cluster, oh no. The target galaxy was modelled after this rather photogenic spiral :

|

| M99, a.k.a. NGC 4254 (do forgive me if I switch between the names), as seen in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. |

|

| Comparison of the optical and gas data. If you look closely, you can see hints of a longer gas stream above VIRGOHI21. |

And yet... it's not that odd. The overall distribution of stars is quite normal, as is the gas in the disc. It's a galaxy that got up on the wrong side of bed one morning and forgot to shower, not a total monstrous freak of nature that should have been killed at birth. Crucially, since it's got an awful lot of gas in the disc (and since that gas disc looks more-or-less normal), if you didn't know about the gas stream you'd never suspect it once had even more gas than it does now. If anything you'd wonder if maybe some interaction had given it extra gas, not ripped some of its gas away from it.

So there are two natural but mutually exclusive interpretations of NGC 4254 : it's pretty normal if you only consider its overall gas and star contents within the disc, or it's really weird if you look at its precise stellar distribution and the long gas stream. That's an interesting circle to square.

All this makes NGC 4254 a great target galaxy, which is why earlier studies used it as a target too. Our model starts off with an idealised version : we create smooth discs of gas and stars which have the same overall distribution, but don't reproduce the one-armed spiral. We also tried varying the gas content and distribution, as well as the mass of the dark matter since that's not so well-determined from the observations. Then we drop this into our galaxy cluster and see if the interactions reproduce any of those peculiar features, or things resembling the isolated clouds. Our cluster includes 400 other galaxies but only as simple point-masses : we don't model their gas and stars (that's far too computationally demanding), just their gravitational effects on the target.

So using M99 as our target may seem odd initially, but actually it lets us tackle several questions all at once :

1) Can we produce isolated gas clouds that look like dark galaxies by harassing a fairly normal spiral galaxy ?

2) What about fake dark galaxies in streams like VIRGOHI21 and the other strange features specific to the M99 system ?

3) Do the properties of the spiral galaxy make a big difference ?

Feel free to skip the next section if you want to get straight to the answers. Keep reading if it want to put these results in a bit more context.

Interlude : The Unnecessary Prequel

Time for a little backstory. One thing the referee and a slightly irate co-author made me tone down in the published paper was the criticism of the previous models. Originally the paper went into great detail about this, and while this was a bit excessive, I still would have preferred to state a few things more explicitly. Well, now I can ! And I will. Watch me.

Until we started re-investigating this, there were basically two explanations for the VIRGOHI21 system :

1) A simulation of Davies 2008 showed that if VIRGOHI21 was a giant dark galaxy, it could have created the stream largely from its own gas as it flew past M99. This could also explain the one prominent spiral arm. Unfortunately this model put VIRGOHI21 very much at the end of the gas stream, not in the middle as is actually the case. Bugger.

2) A simulation by Duc & Bournaud 2008 in which a normal galaxy tears gas out of M99, and VIRGOHI21 is just a kink in the stream rather than a dark galaxy. The "kink" is in the sense that the velocity of the gas changes very sharply as you go from the stream to VIRGOHI21 itself, rather than the stream suddenly changing direction.