As far as the idea that scientists like conformity goes, that's just wrong. Wrongity wrongity wrong wrong wrong wrong wrong. Wrong.

The media is awash with "scientists make breakthrough discovery !" articles, which I've also already railed against here. But, nonetheless, scientists do like discoveries. That's what science is for. And you can't make a discovery, by definition, which isn't in some way new. But you can make discoveries which are expected (boring, but useful) as opposed to those which are unexpected (exciting, but confusing).

Do scientists hate excitement and originality ?

|

| Source. |

|

| I want an extension for Chrome that replaces the "aliens" dude with this image. |

* I'm linking to that newspaper and not any particular story on the grounds that it's a safe bet the headline won't be genuinely exciting. At the time of writing, it reads, "FELLAINI SENT ME PICTURES OF HIS TACKLE !".

The "alien megastructures" are currently only an idea, not a discovery. They are one explanation, others haven't been ruled out yet. Hence the media gets excited, while scientists react more like this :

|

| Let's not lose sight of the fact, though, that many of these exciting "discoveries" are proposed by scientists, which ought to knock the closed-minded charge on the head. |

BICEP2 provides another great example. Here, scientists were looking for a signature of inflation, a very mainstream idea, infinitely more so than aliens building Dyson spheres. Yet when it was proposed that this had been found, the scientific community reacted with strong skepticism - and later this very important mainstream "discovery" turned out to be mistaken. It's a wonderful case of skepticism at its best, questioning even things which agree with mainstream theory. So no, we don't just attack findings which disagree with the consensus. We attack the consensus itself as a matter of course - that's why it's the consensus !

The reason all this matters is because whenever something is presented as a "discovery" when it actually isn't, or when at least equally valid explanations aren't discussed or are marginalised, it makes scientists dismissing the alternatives look like they're doing so because it doesn't fit with the cosy "false consensus" world view. Clickbaiting has a lot to answer for. But then, "Promising new target for SETI" doesn't sound as exciting as "OMG ALIENS !"

But what about when unconventional discoveries turn out to be correct ?

|

| There's not much evidence that Lord Kelvin really said, "X-rays will prove to be a hoax", but they were found by accident. |

More recently, no-one had any reason to think that dark energy existed. Then along came the results of two supernovae surveys, and suddenly we found that the expansion of the Universe was accelerating. Again, mainstream science changed its mind, even though none of our theories gave an obvious explanation for the cause of the acceleration. And in this case, despite still not knowing why the acceleration is happening, the discovery led to the award of a Nobel Prize - which is a pretty clear sign of excitement, in my book.

The idea that scientists don't like non-conformity is like saying that we don't want a revolution, that we somehow think that breakthrough discoveries are a bad thing. But discoveries are the name of the game, so this is basically saying that scientists hate their job. If you've ever talked to a scientist for more than five minutes, I very much doubt you'll agree that this is the case.

It's not that we hate exciting discoveries. It's that we hate getting excited about things which aren't true. Everyone wants to make a name for themselves by making a killer breakthrough (see BICEP2 above), but no-one wants to be remembered as the moron who gave way to premature publication (also see BICEP2 above).

Still, while I think the above dismisses any notion that we don't like excitement or unconventional discoveries, I haven't really addressed the charge that we prefer discoveries which agree with existing ideas. Maybe breakthrough discoveries aren't being entirely shot down, just suppressed and held back longer than they should be.

Well, OK, if scientists don't hate excitement, do they at least prefer to be dull ?

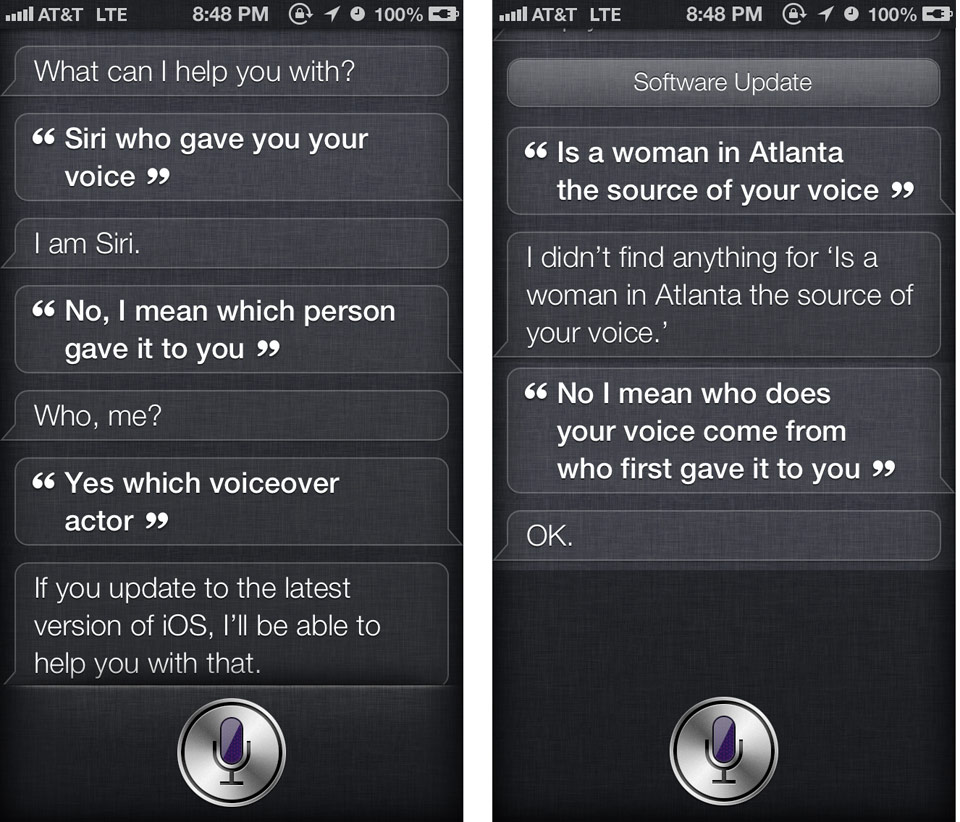

No, but it's good practise not be over-enthusiastic. Science is a slow, careful, and often tedious process. The big breakthroughs are undeniably exciting, but much rarer than the day-to-day process of research. We don't have Star Trek level computers yet. We can't just say, "Computer, run a simulation of solar flares with the observed magnitudes of all flares detected in the last 100 years and compute the probability of disruption to satellite communications in the next six months." The best we've got in terms of automatic language recognition is Siri, and she's not very helpful.

No, we've got to actually look through old records for the data, decide on the best sort of simulation to run, apply for time on a supercomputer to run it, investigate the vulnerabilities of satellites to electronic disruption, etc. etc. etc. for ourselves. Computers are a long way off from replacing researchers.

Science is dull by necessity. Without doing all that work, you can't get to the exciting results. We prefer exciting results which are true, but it's only by doing all those dull tasks, and making all those boring, expected discoveries, that we stand any chance of being sure we've found an exciting result when something interesting crops up. You can't know what's unusual without first knowing what's normal. And you do have to take a certain satisfaction in doing rather a lot of repetitive tasks, otherwise the process would be unbearable.

I personally have long since lost count of the number of times I thought I'd seen something really interesting in a data cube, only to find that it was either a mistake I'd made or a problem with the data itself. 95% of these never even made it to the stage of "I should check with someone else" because I was able to dismiss them very quickly. It wasn't particularly rewarding, but it's a necessary part of the process.

No-one ever gets excited when a paper that's nothing but a catalogue of detections comes out. It's simply that it's not possible to get to the excitement without doing the gruelling legwork. Real science is not much like movie science.

In short, if science appears to be boring and conformal, that's because science is hard. This relates closely to the clickbaiting articles I mentioned earlier : there is a widespread misconception that science is only interesting when it's exciting. The most notable, prominent exception in the mainstream media to this is David Attenborough. The man could easily hold my attention for a full hour talking about nothing except the mating habits of snails, and I'd be absolutely riveted. Yet at no point would I ever feel the urge to leap from my seat, punch the air and shout, "YEEEAH ! SNAIL SEX IS MORE AWESOME THAN SALMA HAYEK WATER SKIING WITH NINJAS AND LASER KITTEN SHARKS !".

Soo... you're saying the false consensus idea is just wrong then ?

Thus far the idea of a false consensus looks to be on very shaky ground. Science is often dull and conformal, but only as a means to the exciting breakthrough discoveries which are possible. Revolutions that completely overturn long-standing theories certainly do happen, just rarely. That's because : 1) We want to be sure we're correct because we hate wrong conclusions; 2) A theory that lasts a long time has stood up to a lot of tests, making it (by definition) a very good theory and therefore harder to disprove; 3) The process of doing science is long and tedious.

I say forget trying to make people excited about science all the time, because it isn't usually exciting. Get them interested instead.

Which is not to say it isn't sometimes very exciting indeed.

The perception that we're all trying to agree with each other largely rests on the media constantly promoting things which are exciting but not true as though they were true, which results in scientists having to repeatedly explain why they're not true, making us look like we disagree because we don't like it.

Aren't you being a bit idealistic ?

So far I've painted a very rosy picture. In the real world, scientists are fallible human beings. They lie, cheat, steal, fornicate, drink, take drugs, rape, murder, create weapons of mass destruction, become assassins, vote for the Conservative party, listen to Celine Dion, and use their enemies skulls as drinking cups. Well... probably not that last one. And apart from the WMD bit, you could say the same for people of any vocation.

As with discrimination in any situation, the question to ask is : does this really represent a wider problem ? Are we seeing a flaw in the system, or just flawed individuals ?

The above is a wonderful piece of satire, but it does emphasise a mood among certain elements that the climate consensus must, somehow, despite all the robustness of the scientific method, either be wrong or just not really exist.

When I encounter reasonable people on the internet, and explain to them what I do and my personal experiences of the scientific method, they sometimes respond with something along the lines on, "Well, of course I didn't mean you, Rhys. I meant that lot. Those darn climate scientists. They're not allowed to publish anything that disagrees with their precious theory."

If that's so, then it's completely at odds with my own experience of the scientific process. I know a number of people personally who hold and publish results which are radically different to the mainstream (some are well-respected figures, some are... not). I'm also aware that human failings do cause problems with the scientific method : sometimes paper referees are overly-harsh, sometimes they will let shoddy work through on a nod if a famous name is on the author list.

(You will have to forgive me, but for obvious reasons I'm not going to name names.)

But the allegation of a false consensus is wholly different. That's saying that almost everyone, everywhere, in every institute, refuses to publish something because they think that either a) it won't get past the referee; b) if it does get past the referee, it will damage their reputation; c) never even considers the possibility / hates the idea in the first place because they're so darn closed-minded.

Options A and B are swiftly dealt with : not every publication is peer reviewed. Conference "proceedings" (the written summary of a conference) are rarely reviewed, and even when they are the review process is not supposed to be as strict as for a regular journal. Consequently they're often much more readable, but not as detailed or as reliable, than regular publications - but I've never seen a proceeding article that differed radically from the reviewed version*. As for option B : nah, also silly, I know plenty of people who don't give a hoot about their reputation - even at the expense of their funding.

* And I'll add that even in refereed articles, you can generally say whatever you like as long as you make it clear when you're speculating.

Option C, however, is more serious - because I do know people who are so closed-minded that they refuse to consider certain ideas. That includes people who are so ultra-mainstream they think we've basically got everything licked and laugh in the face of alternatives, and people who are so anti-mainstream they think their silly pet theory has trumped Einstein. Individual scientists are certainly capable of being dogmatic.

But the idea that the system as a whole is so closed is pure nonsense. MOND isn't a mainstream theory, but papers get published on it all the time (26 papers so far this year with MOND in the title). No less a mainstream institution than the Monthly Notices of the Royal Freakin' Astronomical Society has published papers on cyclic extinction events (an idea that's been controversial for thirty years or so), at least two papers about dark matter causing the untimely demise of the dinosaurs, and recently one has been submitted about aliens building megastructures around that star. And the equally respected Astrophysical Journal published one this year about looking for Dyson spheres via the Tully-Fisher relation, for crying out loud.

|

| Maybe it was a passing Dyson sphere, deflected by the dark matter in the galactic disc, that disturbed the Oort cloud and sent in the comet that killed the dinosaurs. Yeah. |

* I was lectured by his even more controversial collaborator Chandra Wickramasinghe.

Obviously I write everything with the bias of an astronomer. I can't do anything else. All I can say is that if climate scientists really are behaving as their detractors allege, then they are acting in a way that's preposterously alien to me.

(As far as media excitement is to blame, it works both ways for climate change. Without being a climate scientist, experience of this process in astronomy tells me to be way both of scientists claiming they've solved everything through a natural mechanism, and of those claiming we're all going to die by 2050 due to methane eruptions and there's absolutely nothing we can do about it)

Didn't you say you were worried about a false consensus ? It sounds like you think it's almost impossible.

Indeed. So why do I say that there's any truth at all in the allegation of a false consensus ? Three reasons :

1) Big science

|

| CERN played an important role in the invention of the internet (which alone more than justifies the money spent on it), but only as a spin-off, not as a direct result of the research being done. |

Of course not all big facilities operate in the same way. Instruments like the LHC are designed to do a few specific tasks by enormous groups of people. Telescopes are generally run as observatories which are operated and maintained by a single largeish group, but usually used by dozens of much smaller external groups who have no vested interest in that particular facility, theory or even subject (Arecibo does everything from the atmosphere to distant galaxies; ALMA looks not just at molecular gas in other galaxies but also the Sun).

Big, open-time telescopes (which anyone can apply to use) are a great example of combining the power of big instruments with the creativity and flexibility of small groups. Sometimes we also need large, dedicated facilities to test single specific ideas - the trick is not to let those facilities dominate the world of science. For more on this, see this essay by noted "I love dark matter !" astronomer Simon White.

2) Publish or perish

Assessing people by their number of publications makes very little sense (disclaimer, I'm biased). Not all papers are created equal; no individual is ever perfectly objective and everyone makes mistakes. But worse, if your career depends on publishing as much as possible, you're innately encouraged to write mediocre papers that the journals can't refuse to publish but which don't actually advance science in the slightest. It may look great on paper if you've got twenty papers but it doesn't mean a thing if they're all crap.

Perhaps we need a new publication system which recognises that yes, pretty much all research needs to be published, but differentiates between style and content more precisely. Cataloguing observations is essential, but is a fundamentally different task to inferring what they mean. Currently authors options are either a) a regular journal or b) publishing in the overly-prestigious Nature or Science. There's not much middle ground. Maybe there should be more. We don't necessarily need more journals, just more sections within journals to differentiate content.

3) Science by grant

If you're a tenured professor, you yourself can do pretty much whatever research you want. At the postdoctoral level this is rarer : you're often expected to work only on a specific project*. Frequently this is because your source of funding comes not directly from your research institute or university, but an external grant agency. Your hands are tied; if you come up with a brilliant idea that's nothing to do with what you work on, you probably won't have time to pursue it because your funding doesn't permit it.

* I'm not, though as a student I didn't have time to write my own galaxy-finding code so I did it during some late-night observations. It worked pretty well, and became an important part of the resulting publication and thesis. As a postdoc, I initially didn't have time to work on my data-viewing code, so I did it at home when I was bored. Eventually it became a paper in its own right. Sometimes discoveries happen when you're most free to play around without fear of failure.

Which sucks. Professors tend to spend a lot of time teaching, managing students, and writing grant applications to hire new staff. They fit whatever research they can in around this. Consequently we have this strange system where the ones doing most of the work are the ones least free to innovate, and the ones doing the least frontline research have the most experience. The solution ? End the grant system. Give more money to universities to hire staff as they see fit. Trust in scientists to do their job and don't tie their hands by external agencies.

The grant system isn't exactly causing a false consensus, because it doesn't enforce finding only specific conclusions. But it does limit thinking and stifle innovation, which is false consensuses' ugly cousin.

Conclusions

If there is any scientific discipline in which the public might legitimately say, "well you would say that wouldn't you, you're a scientist", it is not astronomy. There are so many examples both past and present of astronomers throwing out crazy ideas and getting them published that the idea of a false consensus looks absurd. So if you throw out an idea and every astronomer shoots it down, here's a thought : maybe it really is just because your idea is bonkers.

But even in astronomy we've seen how there can be flaws in the system. Astronomy has always been a big science, nothing wrong with that provided things are managed correctly. All we need to avoid on that front is relying exclusively on huge research teams, which are ill-suited to innovation. The publication and grant cultures are more damaging.

To some extent these problems are a result of trying to quantify the unquantifiable. You can't put a number on how good a scientist someone is, and it's a mistake to try. If you've written a lot of papers, that means you're good at writing papers. It tells you nothing about the quality of the work. And yes, I have an example in mind of a famous group who do publish some genuinely outstanding research but a lot more mediocre stuff as well, though I'm not going to name names.

The grant system is similarly a result of trying to do science like it's a business : this person shall work on project X, this one on project Y, we shall all be in work 9-5, we'll never take coffee breaks, etc., the most important thing is that we have productive output, gotta keep the taxpayers happy. But running a scientific institute in this way (as some would like) is ultimately self-defeating. Allowing people to work how and when they choose and publish when they want to publish does not mean you can't evaluate their performance, but it does mean that you can't reduce them to their number of publications.

Science and the arts have something in common : to do either of them well, you need to innovate, to think creatively. You can't force new ideas by chaining someone to a desk. You can't guarantee that they'll happen at all, but you can encourage them through getting people to talk to each other, by fostering a free-thinking, informal atmosphere. Most importantly of all, they need to feel free to fail, to pursue crazy ideas that might take months and end up being useless. To really innovate, you need to take risks. Grant-based research, which expects this many results about this project, is not suitable for this.

Those societies in which seriousness, tradition, conformity and adherence to long-established - often god-prescribed - ways of doing things are the strictly enforced rule, have always been the majority across time and throughout the world.... To them, change is always suspect and usually damnable, and they hardly ever contribute to human development. By contrast, social, artistic and scientific progress as well as technological advance are most evident where the ruling culture and ideology give men and women permission to play, whether with ideas, beliefs, principles or materials. And where playful science changes people's understanding of the way the physical world works, political change, even revolution, is rarely far behind.

- Paul Kriwaczek, BabylonTo summarise then, here are a few ways to avoid a false consensus and demonstrate this to the public :

- Be more interesting and less exciting. The media desperately need to learn that the most exciting solution is not usually the correct one, nor the one favoured by the majority - and those two facts are not unrelated. False excitement is at least partly to blame for this image of the false consensus / closed-minded attitude.

- Do more outreach. That's always good advice. In particular ram it down people's throats that the findings of science are evidence-based and provisional. Tell people about the methods, not just the results.

- Teach people about statistics in primary school. When a few scientists dissent from the prevailing opinion or make controversial statements, that does not automatically make everyone else wrong or even more likely to be wrong.

- Emphasise controversies where they do exist. They are an asset to science, not a danger.

- Don't rely exclusively on large teams at big facilities. Smaller groups are much more flexible and innovative.

- End the "publish or perish" culture. More publications does not guarantee better science is being done, and can in fact lead to exactly the opposite.

- End the grant-based funding process. To be innovative, scientists must be free to take real risks, to pursue projects with no guarantee of success. They must be free to play, to try things on a whim for no other reason than to see what will happen, not because some bureaucrat thought it would look good to tick a box on a form.

Some older folk like me Rhys rember Climate Gate, so for instance when I saw Michael Manns article in the Guardian Earlier I do have to bite my tongue ( Hockey Stick and Climategate). That said I have just read his Rosby Wave paper and its very interesting. Now Things effecting the Upper atmosphere, and gulf stream ? is that your line of country. I know that Pirs Corbyn has his own take on the SOlar and interstellar phenopmena effecting Earths CLimate and weather, he does a presentation with a floppy string draped around a blow up globe, very good value it is too.https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/aug/28/climate-change-hurricane-harvey-more-deadly

ReplyDeleteCorbyn.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6R26PXRrgds

Climate Gate. A Sample.

http://letthemconfectsweeterlies.blogspot.se/2017/03/climate-gate-getting-deeper-into-detail.html

Many thanks. For me it was useful.

ReplyDeleteThank you for this post.This is very interesting information for me.

ReplyDelete