Marine Le Pen, right-wing French nutter, was recently "uninvited" to a technology conference. Nicola Sturgeon, leftist leader of Scotland, is boycotting an event featuring badly-groomed nutcase Steve Bannon. Predictably enough, these choices triggered concerns that they might provoke a sort-of variant of the notorious backfire effect, in which an attempt at persuasion causes someone to hold more strongly to their original opinion. The hope is that by banning a speaker, they have less of a platform from which to attract supporters and less legitimacy; the fear was that the ban would attract more attention than if they were allowed to attend. Similar claims and concerns beset every incident of "no platforming".

The backfire and Streisand effects are distinctly different : the backfire effect is when an argument causes or strengthens the opposite belief it was intended to, while the Streisand effect is when restricting speech attracts unwanted attention. Both share the common feature of being an effect opposite to the intention, and while not the same they are not mutually exclusive either. Both relate to the moral principles and effectiveness of attempts to control the flow of information.

This is the first of three posts in which I'll concentrate on the effectiveness. In particular, under what circumstances do bans successfully prevent the flow of information and when do they have the opposite effect ? When they backfire, do they cause a wider spread of information or does it only strengthen existing belief, or both ? Or neither ? When does exposing a viewpoint only harm its supporters, and under what conditions does it help normalise the idea and help it spread further ?

In this first introductory post, I'll concentrate on persuading individuals and the effects that arguments can have on them in isolation. In particular I'll give some extreme examples to illustrate the main point : that it's not the ideas themselves which matter, it's their conditions which govern whether they will attract unwanted attention or simply fall on deaf ears. In the second I'll summarise the more general, typical causes of successful and unsuccessful persuasion. Finally in the third I'll examine the flow of information in groups and why this isn't as simple as the persuasive techniques used between individuals. Although there are plenty of links to my own musings, for the most part I've tried to make this one into more of a compendium of findings from actual psychological studies.

So, let's begin.

When the backfire effect doesn't happen

The backfire effect is so popular on the internet that sometimes one gets the impression it's an inviolable law of nature that can never be avoided. Let's start by knocking that one on the head and start with some simple hypothetical examples that may lead us to more general trends.

Do you always decide to believe the opposite of what anyone says under any circumstances ? Or is your sense of morbid curiosity always inflamed whenever someone tells you not to do something ? Of course not. If your dear old mum tells you it's raining outside, you don't insist that it must be sunny. And you definitely won't insist on continuing to believe that it's sunny if she was proven correct on checking. That level of irrationality is very rare indeed. Even if you already thought that it was sunny - say you'd looked outside yourself a few minutes ago - what this new information will generally cause is not, I'd say, active disbelief, but simple, momentary confusion. You probably won't even feel inclined to check at all : you'll accept it without question, on trust. In fact you won't even care.

Or suppose some lunatic claimed to have discovered a goose that laid

* It's an under-appreciated fact that most things people say on the internet do not go viral. The overwhelmingly vast majority of discussions remain extremely limited and don't propagate in the slightest. Or maybe it's just me being reeeeally boring... ?

** Not to be confused with the Magical Moose, of course.

So in this example the backfire effect would occur, but it would obviously be the lunatic who was distrusted, not the media. Why ? Because anyone with an ounce of rational judgement can instantly say that the madman's claim is far more probable to be nonsense, and thus they would lower their trust level of the lunatic and possibly even increase their trust in the media (if they had reported it, they'd have been criticised as being gutter press - "give us some real news !"). Only other lunatics would behave in the opposite way. There would be no Streisand effect at all, and no backfire effect on the media.

Or to put it another way, people have access to multiple sources of information. Shouting about a bitcoin-laying goose is in such absolute contradiction to all of those other sources - science, direct observation, etc. - that it couldn't be believed by anyone rational.

Now imagine that the media decided to actively report on the fact that they weren't reporting a story. "Nope, there's definitely nothing interesting about ol' farmer Bob, he's just a crazy old coot." Well, if there's nothing interesting, why in the world are they even reporting it ? Suddenly I really wanna know who farmer Bob is and why they're not reporting on him ! An active, promoted ban is like having evidence of absence (there must have been something to search for, something that can be absent), which is very different from a complete lack of reporting, which is more like having absence of evidence.

Yet while this will certainly draw attention to the issue that it wouldn't have otherwise had, and it might sow distrust in the media, it still definitely won't cause more people to become more receptive to the possibility of magical geese who weren't receptive anyway. Oh, it'll cause more people to believe in magical geese, yes, but only by reaching a greater a number of plonkers than the case of pure non-reporting. It won't make anyone the slightest bit more susceptible to believing nonsense. There's a big difference between spreading information and causing belief, and an even bigger difference between making people hold rational conclusions and them actually being capable of rational judgement.

And the thing about actively-reported bans is that these effects are largely temporary anyway, because few of them stay actively reported for very long. Stories about people being unwelcome in certain venues tend to last about a day or two in the media but rarely longer than that because they quickly become uninteresting non-stories. Only very rarely does this ever seem to cause a viral story with mass attention it wouldn't have otherwise received. Novelty would seem to be an important factor - usually when a speaker is barred, we already know the gist of what they would have said, whereas with information - books, music, academic papers - curiosity is inflamed. The Streisand effect seems to be more related to what they wanted to say than who was trying to say it.

All this presumes both that most people are basically rational and that the media are trusted. The situation is completely different if there's a chronic culture of media untrustworthiness : if the media are not trusted, then nothing they say can be believed. And how can you have people behaving rationally and believing rational things if they have no coherent, reliable information to assess ? You can't. Isolated examples of nonsense simply cause the inherently irrational to more fully develop their own irrationality; in contrast an endemic culture of reporting gibberish inevitably has the entirely different effect of actually making people irrational. You cannot have a rational society without trusted information.

|

| Which is why, given the chronically irrational state of British politics, there's a non-negligible chance I'll be voting for these guys at the next election. |

We also know that there are entirely ethical persuasive techniques that give measurable, significant increases in appropriate responses that don't use or cause the backfire effect at all. And there are methods of argument that are specifically designed to avoid the backfire effect. More on these in part two.

At least one study has gone to the extreme and claimed that the backfire effect actually never happens. #Irony, because that surely encourages believers in the backfire effect to believe in it more strongly... it's most likely an overstatement, but the study was quite careful so we shouldn't dismiss it out of hand. It suggests, I think, further evidence that it's not inevitable, and may depend much more strongly on how the counter-arguments are framed than we might have guessed. The broader social context - e.g. current global affairs - and raw factual content may play only minor influential roles. Stating the blunt facts is not enough in itself to cause a backfire, even if they have obvious, emotional consequences. Rather it's about how those statements are presented and in what context : who says them, how they make the other side feel, and what alternatives are available.

When the backfire effect does happen

The backfire effect may not be ubiquitous, but it's hardly a rarity. Think of the last time you heard a politician speak, and I bet there's a fair chance you ended up believing the opposite of what they intended - unless you already agreed with them. Or better yet, not an actual politician but a political activist : someone trying to promote belief in broad ideologies, not necessarily specific policies.

The backfire effect happens largely when you already dislike something : either that specific piece of information, or, perhaps more interestingly, you have other reasons to be predisposed to disliking a new idea. There's also a very important distinction between disliking the source and disliking what it says. For example, I loathe Gizmodo's sanctimonious reviews of apolitical products, e.g. movies, but they tend to make me hate Gizmodo itself more than they ever make me hate whatever it is they're reviewing.

|

| It doesn't always react like this to all new concepts, of course. |

Even more subtle, you might hate an argument but that doesn't necessarily mean you don't accept it. The acceptance level and emotional approval of an idea are surely correlated, but they're not the same thing. I mean, Doctor Who is wonderful and all, but it's not a documentary. I might accept its moral teachings but reject its wibbly-wobbly, pseudo-weudoy "science". Or I might reject that it has any applicability to the real world at all, including its moral commentary, but still find it entertaining. Political satire provides another case of enjoyable lies that attempt to reveal deeper truths.

Perhaps the simplest case might be when you've already formed a firm conclusion about something and then you encounter a counter-argument. Depending on the amount of effort it's taken for you to reach your conclusion, and especially if you're emotionally invested in it, the opposing view may not go down well. But even here there are subtleties - again, it might just cause you to dislike the source, not believe any more strongly in your view. And even that might be temporary : when you just casually read something you think is stupid on the internet, you can simply say, "that's stupid", move on, and that mildly unpleasant incident might not even persist in your long-term memory at all. Things you dislike can thus have no impact whatsoever.

There are a couple of possibilities which might cause a genuine strengthening of your belief. The argument itself may do this, depending on how it's framed : saying, "all Doctor Who fans are stupid" isn't going to stop anyone from watching Doctor Who, and might even make them enjoy it more : it induces a group identity, they will now make their Doctor Who fandom a - slightly - more important part of their identity. Or it may simply press the wrong buttons, using emotional rhetoric ("Daleks are shite !") for people who want hard data ("Daleks only exterminate 24.2% of people they interact with !"), or vice-versa, only using hard data for people who need an emotional component. Or it may use ideas and evidence the opponent is already convinced aren't true, automatically giving them reasons to be suspicious. Or perhaps the supporting reasoning is fine but only the final conclusion isn't compatible with their existing beliefs, or at least isn't presented as such. There are indeed very many ways in which a persuasive technique can go wrong, with large variations between individuals*. Unfortunately, one man's compelling argument is another's pointless and deluded ranting.

* Witness the success of targeted advertising, with the significant caveat that advertising isn't terribly effective so improvements aren't necessarily that difficult.

A more interesting failure may occur with rebuttals. One important lesson from school debates (and indeed the above links), where we often had to argue positions opposite to what we initially thought, was that this emotional attachment does cause a true shift in stance. Getting people to argue for something gives them a sense of ownership; it becomes part of their identity (not necessarily a very important one, but it doesn't have to be). Counter-arguments are then registered by the brain in the same way as attacks, even if the argument wasn't personal at all. While it surely helps to avoid saying that the other guy is a stinky goat-fondling loser whose mother was a cactus, that's not always enough. Mere argument with the issue itself is subconsciously perceived as an attack whether we intend it as such or not (though in a carefully managed situation explicitly framed as a debate, this is not necessarily the case).

And we're not always on our own either - we may be part of a group. Feedback plays an important role. If people praise us for what we say, we're more likely to believe it. So if we're receiving praise from "our side", and criticism from those smelly losers, then even the carefully-stated, well-reasoned statements of the other side may struggle in vain and cause us to dig our heels in deeper. This is perhaps why certain philosophers preferred to debate people one-on-one or in small groups, never en masse.

Note the key difference between changing a strength of belief (making you hate Doctor Who even more than you already do) and changing the stance (making who hate Doctor Who when you previously liked it). Techniques to cause both effects are not necessarily the same : insulting members of different groups isn't going to cause them to like you, but it may strengthen the bonds within your own group. Most political memes, on that basis, seem to make a massive error by trying to rally support, seeking to motivate the existing troops rather than gain new recruits. More on that in the other posts.

Who do you trust ?

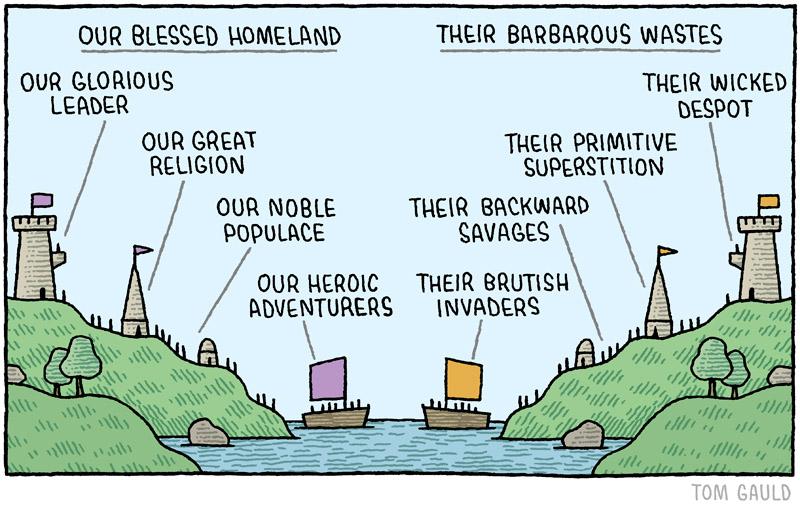

So while hating the source doesn't automatically lead to disbelieving an argument, it can eventually have an even stronger effect. One possibility is, as mentioned, that we don't trust anything at all, becoming pretty much entirely irrational about everything. Another is that we fall victim to extreme tribalism, entering what some people call an echo chamber, an epistemic bubble, or what I like to call a bias spiral.

When you despise a source strongly enough, you may be capable of hearing their arguments but not really listening to them. Every vile word that comes out of their whore mouth is processed not as legitimate information, but wholly as evidence of their partisan bias. If they give you evidence - even really good, objective evidence - that counters your belief, you may see it only as a further indication of their own ideological ensnarement. This is both a manifestation of and route to absolutist thinking, where you already know the facts so any contradictory statements are simply evidence that the other side is lying, stupid, or themselves trapped in their own cult-like filter bubble. You have in effect become inoculated against opposing ideas, and can listen to them freely but with little chance of them ever making any difference. Everything the opposition says can have a backfire effect. Which isn't good.

|

| Not listening is bad enough, but perverting evidence is much worse. |

That's a really extreme case, of course. A more common, lesser manifestation is activist thinking : at some point, we all want to convince others of something because we genuinely believe we're right. Someone who is on an active campaign of persuasion isn't themselves very receptive to persuasion. They've made it their mission to change everyone else's mind, so psychologically it will be extremely difficult for them to admit they're wrong. Techniques here have to be slow and subtle, gradually undermining the reasons for their conclusion but never letting them suspect this threatens the conclusion itself; gradually getting them to find ways to undermine their own idea rather than telling them they're a nutcase (even if they are).

Which of course raises the issue of how to judge if someone is crazy, and the even more complex issue of how to decide what's true (which for obvious reasons I'm largely avoiding). One fascinating idea is that you should examine their metaknowledge : ask them how many people agree or disagree with them. The most informed people who have investigated ideas in the most depth don't just know about one option, but have broad knowledge of the alternatives as well. And this means they have the most accurate knowledge of how many people believe which idea, which is something that can be reliably and directly measured.

So if you're looking for someone to trust, look for someone with accurate metaknowledge; if you want to judge which idea is correct, look not just at the broad expert consensus but the consensus of the experts with the best metaknowledge. For example most Flat Earthers are probably aware they're a minority, but most of them will assess this far less accurately than genuine astrophysicists.

This won't be perfect. Science isn't a done deal, because that is simply not how it works. All you can do is judge which theory is most likely to be correct given the present state of knowledge. Understanding of group knowledge is a good guide to this - but of course, it has its own flaws.

Persuasion also requires time. Of course when we do enter into activist mode, as we occasionally must, we all hope that we'll argue with people and convince them in short order, landing some "killer argument" that they can't possibly disagree with. This is a laudable hope, but it may not be a reasonable expectation. Instead, presume that the best result you'll achieve is to plant the seed of doubt. Arguing for uncertainty first gives that seed a chance to germinate later. We'll look at some of the reasons for this in parts two and three.

Summary

People are weird and complicated. They don't have buttons you can press to get whatever result you want. But there do seem to be some plausible, useful guidelines. In general you can't just say, "go over there !", but you might be able to steer them in the direction you want them to do. For instance, consider the extremes :

- If you tell someone who trusts and respects you some information that doesn't conflict with their ideologies, is consistent with their existing ideas and expectations, only adds incrementally to what they already know, makes them happy, is trivial to verify, and you say it in a nice, respectful way, then there's very little chance of it backfiring. The worst you can expect is that they might go and check it for themselves, if it's something that excites their curiosity. They won't even do this if they don't care about it.

- If someone despises you and thinks you're an idiot, and you come along with some idea that's completely at variance with their established beliefs, requires a huge conceptual shift in their understanding, makes them angry, makes them start arguing but really requires expert analysis to check properly, and you garnish it with insults, then this is almost certain to backfire. At the very least, it's ridiculously unlikely to persuade them of anything, and might just cause them to hate you even more. If they didn't care about it before, they may start to do so now. And if it's something they already care about, curiosity will be of no help : they might start to further rationalise their position rather than examine it.

|

| Of course, if it turns out they're actually more like Spock, then you'll have to change tactics. |

And we've also seen that there's an important distinction between your opinion of the source and your opinion of the idea. The two are interrelated, but in a complex way. Arguments you dislike cause you to distrust a source, and vice-versa. It really should come as absolutely no surprise to anyone that if you get people to listen to opposing political opinions, i.e. people they don't like saying things they don't like, they become more polarised, not less. It's nothing to do with people just not listening to the other side, that's not it at all. Although people do sometimes attack straw men, in my experience this claim is massively over-used. More typically, it's precisely because they've already listened to the other side that they decided they don't like them, so further contact isn't going to be of any help.

Yet in other circumstances the opposite happens. The conditions in which people trust the evidence presented are not entirely straightforward : more on that in part two.

While I'll look at how information flows in groups in part three, we've already seen how attracting attention to an idea is largely a matter of curiosity. I've claimed that this means the Streisand effect occurs during a botched attempt to hide information. No-platforming efforts seldom cause prolonged mass interest, except perhaps to those who weren't familiar with the speaker anyway, whereas banning, say, a new music track has often caused sales to spike. Reporting the ban inflames curiosity even further, whereas just not mentioning it all can be much more successful. Banning is more likely to cause believers to harden their position than it is to create new believers.

Superinjunctions, a law forbidding the reporting of (say) a crime, the alleged criminals, and the superinjunction itself, are perhaps the worst case : even a tiny failure, a minuscule leak, will send curiosity levels soaring because so much information is hidden. It's not really the people involved that excites curiosity, it's what they said and did.

I'll end with a personal example. Back in 2016 there were rumours that a British celebrity was involved in a sex scandal. Nothing unusual about that, except that the British media were forbidden from reporting any details at all. Had they just told us it was Elton John, I wouldn't have cared an iota. But they didn't, so I specifically trawled the internet just for the point of finding out who it was. I still didn't care about either the issue itself, or even who it was, really (at most I was mildly curious), I just wanted to see if I could overcome the "ban". It wasn't, I have to say, entirely easy, but it wasn't impossible either. At first the difficulty became a motivation to continue, though after a while it began to seem like a motivation to stop. However, had I been a bit less motivated (or just busier), or had the search been just a little harder, the super-injunction could have succeeded.

More of that in part three. Next time I'll look in more detail at how techniques of persuasion work, and how while people can sometimes be extremely easy to convince, at other times they are impossibly stubborn. Knowing persuasive techniques can help, but sometimes it's better to step back and not enter the discussion at all.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Due to a small but consistent influx of spam, comments will now be checked before publishing. Only egregious spam/illegal/racist crap will be disapproved, everything else will be published.