At last, it's time to finish this series on Tolkien by trying to answer the biggest questions of all. We've moved from the scales of individual objects, peoples, the landscape, and the very world itself. We've seen the influence of Tolkien's moral beliefs at work at every stage, a complex and astoundingly well-crafted use of symbolism and metaphor that embodies some very fundamental beliefs, giving physical shape to our fears and hopes. Now we must consider things on a truly global scale and beyond : Arda as a planet and its place in the cosmos.

5) Cosmos

World Enough : The Shape of Arda

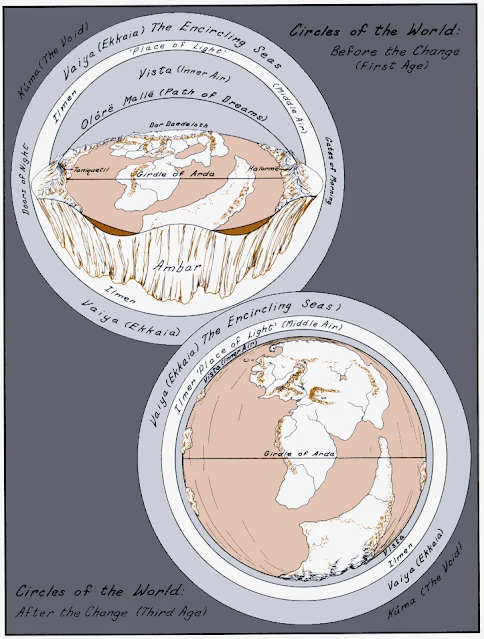

I've heard that the changeable nature of the shape of the world is due to editorial changes by Christopher Tolkien, and that J. R. R. said later that it should always have been round. But no matter, I very much like the way this is depicted in the final published version of The Silmarillion : it is fully consistent with a story of the world becoming less mythical and more real.

Initially, Arda is flat. The geometry therefore seems simple enough : there are continents in an ocean, and you can literally sail to heaven and return. However, in The Atlas, Fonstad notes that Tolkien's maps even of the Third Age depict the world as though it was flat when it was clearly supposed to be round. She notes that in the phrase :

...it was globed amid the Void, and it was sustained therein, but was not of it.

There is an apparent contradiction, which is resolved by Arda's ability to be both round and flat. A further dilemma is that Tolkien did not appear to take into account the projection effects of mapping a round world to a flat sheet, so that as a professional cartographer, she finds, "The only reasonable solution is to map his maps – treating the his round world as if it were flat. Then Middle Earth will appear to us as it did to Tolkien."

But this we can safely attribute to something as mundane as Tolkien not being concerned with geometric precision; whether the shortest path between Gondor and Hobbiton is a straight line or a curve makes no difference to the narrative. I also think that "globed" in the above quote just means "enclosed in" rather than "it was round and inside the void".

Much more interestingly, Fonstad also notes that Tolkien's use of "the encircling seas" and other boundaries of the world do not appear to reflect ordinary physical boundaries. When Melkor destroyed the Lamps, the Valar are forced to relocate :

Therefore they departed from Middle-earth and went to the Land of Aman, the westernmost of all lands upon the borders of the world; for its west shores looked upon the Outer Sea, that is called by the Elves Ekkaia, encircling the Kingdom of Arda. How wide is that sea none know but the Valar; and beyond it are the Walls of the Night.

Later the Númenóreans embark on long voyages :

...from the darkness of the North to the heats of the South, and beyond the South to the Nether Darkness; and they came even into the inner seas, and sailed about Middle-earth and glimpsed from their high prows the Gates of Morning in the East.

Fonstad notes that the "encircling seas" should not be taken literally. Her depiction of the state of affairs needs to be considered carefully :

Prior to the change, the usage of the phrase, "Circles of the World" referred not to a planetary spherical shape, but rather to the physical outer limits or "confines". The maps and diagrams in The Shaping of Middle Earth, "The Ambarkanta" all confirm this interpretation.

The removal of Valinor seems to support this. Its removal is not quite a discrete process, first becoming less and less clearly visible from Númenór before its final excision. Tolkien here piles myths atop myths :

For Ilúvatar cast back the Great Seas west of Middle-earth, and the Empty Lands east of it, and new lands and new seas were made; and the world was diminished, for Valinor and Eressëa were taken from it into the realm of hidden things.

Although I've seen the word "diminished" taken literally to mean the world becoming smaller, clearly this also means that Arda is reduced in quality, deprived of Valinor as if one lost something precious. Yet while the physical connection from Middle Earth to Valinor is severed, the path between the two is not wholly lost :

Thus in after days, what by the voyages of ships, what by lore and starcraft, the kings of Men knew that the world was indeed made round, and yet the Eldar were permitted still to depart and to come to the Ancient West and to Avallónë, if they would. Therefore the loremasters of Men said that a Straight Road must still be, for those that were permitted to find it.

I imagine such a voyage looking very much as depicted in Amazon's The Rings of Power : an ordinary sailing ship approaching some formless light. Travellers would not experience the sea changing beneath them until, perhaps, they ascended to Valinor itself. The notion of a Straight Road, which Fonstad draws as a simple arrow, is not to be taken as some sort of interstellar aqueduct, not a Rainbow Bridge as in the Thor movies.

|

| It very specifically does not look like this. |

Tolkien's own description I take as firmly as metaphorical :

And they taught that, while the new world fell away, the old road and the path of the memory of the West still went on, as it were a mighty bridge invisible that passed through the air of breath and of flight (which were bent now as the world was bent), and traversed Ilmen which flesh unaided cannot endure, until it came to Tol Eressëa, the Lonely Isle, and maybe even beyond, to Valinor, where the Valar still dwell and watch the unfolding of the story of the world.

I don't think distant observers would see the ship being drawn up into heaven nor there being some physical channel of water through which it would go. At some point the ship would no longer be visible, but what they'd see is probably best left to ambiguity. Often in The Silmarillion and elsewhere, Tolkien himself appears to be uncertain, or wishes the reader to be uncertain, because once again, a tale can't have a legendary quality if it's known with total clarity. And so it is with later voyages to Valinor long after its removal :

And tales and rumours arose along the shores of the sea concerning mariners and men forlorn upon the water who, by some fate or grace or favour of the Valar, had entered in upon the Straight Way and seen the face of the world sink below them, and so had come to the lamplit quays of Avallónë, or verily to the last beaches on the margin of Aman, and there had looked upon the White Mountain, dreadful and beautiful, before they died.

And Time : The Sun and Moon

|

| Tilion and Arien, respectively guardians of the Moon and Sun, as depicted on DeviantArt. |

The loss of Valinor again shows the world becoming less mythological and ever-more materialistic. The Straight Road persists until at least the Third Age, but as it is not a physical "Road", perhaps its existence continues indefinitely. With the mention of "Avalon" and Tolkien saying that Númenór becomes known in later days as Atlantis, both being myths recorded in actual history, it seems that Tolkien clearly sets his vision in reality. The Atlas quotes him from an interview :

"If you really want to know what Middle Earth is based on, it's my wonder and delight in the Earth as it is, particularly the natural earth."

And in Appendix D of The Lord of the Rings he is even more direct :

The year no doubt was of the same length, for long ago as those times are now reckoned in years and lives of men, they were not very remote according to the memory of the Earth.

So while I've also heard it said that Tolkien later decided Middle Earth was not to be a mythology of Europe, as is popularly supposed, I tend to discount this. Of course he doesn't mean to suggest these events actually happened (!), but the fiction is clearly set within our world. Whether this means we can really call it high fantasy or not I leave to extreme pedants - go on, knock yourselves out.

But how remote, how long ago exactly ? This is left unsaid. Thousands of years at least, tens or hundreds of thousands quite possibly, millions at the outset, but surely not more than a few million. It may be interesting to put Tolkien's publications in the context of the changing scientific estimates of the age of the Earth, from tens of millions of years at the beginning of the twentieth century to the modern value of 4.5 billion years by the time of the publication of The Lord of the Rings. How widespread these findings were in the general public, and whether or not Tolkien himself knew or cared, I don't know.

Fortunately Tolkienian cosmology is explicitly mythological and not intended as a literal description as with full-blown Creationism. In The Silmarillion, the Sun and Moon are created from the last blooms of the Two Trees :

The flower and the fruit Yavanna gave to Aulë, and Manwë hallowed them, and Aulë and his people made vessels to hold them and preserve their radiance: as is said in the Narsilion, the Song of the Sun and Moon. These vessels the Valar gave to Varda, that they might become lamps of heaven, outshining the ancient stars, being nearer to Arda; and she gave them power to traverse the lower regions of Ilmen, and set them to voyage upon appointed courses above the girdle of the Earth from the West unto the East and to return.

Isil the Sheen the Vanyar of old named the Moon, flower of Telperion in Valinor; and Anar the Fire-golden, fruit of Laurelin, they named the Sun. But the Noldor named them also Rána, the Wayward, and Vása, the Heart of Fire, that awakens and consumes; for the Sun was set as a sign for the awakening of Men and the waning of the Elves, but the Moon cherishes their memory.

These two "lamps of heaven" are attended on their "islands" by two sapient beings. As with other lights they fill Morgoth with fear, who assaults them but their blinding majesty is too powerful. Essentially in order to prevent the possibility of an intrasolar traffic-jam, they coordinate their movements together so that Middle Earth experiences the full range of conditions from true darkness to twilight to full daylight. Likewise their movements about the sky have both explicit purpose and intentional design. This is high myth. Furthermore, they provide evidence that even when Arda was "flat", we should not take this too literally, or at the least it isn't a thin disc :

Tilion tarried seldom in Valinor, but more often would pass swiftly over the western land, over Avathar, or Araman, or Valinor, and plunge in the chasm beyond the Outer Sea, pursuing his way alone amid the grots and caverns at the roots of Arda. There he would often wander long, and late would return.

Which continues to suggest something more symbolic to the whole structure of Eä than the literal flying turtles and elephants of the Discworld. For one thing a "chasm" beyond the sea doesn't make much sense. For another, how deep to the "grots and caverns at the roots" go ? As with sailing off into the sea, it seems unlikely to have a distinct edge. There exists in Eä a flat land of Arda which is normal and comprehensible, but it's set within a realm not based on any physics, or even geometry.

What does all this have to do with time ? Well, the lights of the Sun and Moon are obviously used for marking time, but they recall the earlier era of the Two Trees :

Each day of the Valar in Aman contained twelve hours, and ended with the second mingling of the lights, in which Laurelin was waning but Telperion was waxing. But the light that was spilled from the trees endured long, ere it was taken up into the airs or sank down into the earth; and the dews of Telperion and the rain that fell from Laurelin Varda hoarded in great vats like shining lakes, that were to all the land of the Valar as wells of water and of light. Thus began the Days of the Bliss of Valinor; and thus began also the Count of Time.

Time itself begins with the Trees and their waxing and waning. Or so it seems, because here things are bordering on incomprehensible, I think intentionally so. Battles have already been lost and won before the Trees, change is a part of Arda from its inception. How does this proceed without Time ?

Answer : it just does.

Tolkien does not attempt to answer this directly, as Pratchett does in Discworld : Death's domain is one in which there is no time, but some sort of "duration" that allows characters to move around, think, sleep, fry puddings and so on all without aging in the real world. Tolkien instead completely avoids the issue. Much is left unsaid of the creation of the world :

So began their great labours in wastes unmeasured and unexplored, and in ages uncounted and forgotten, until in the Deeps of Time and in the midst of the vast halls of Eä there came to be that hour and that place where was made the habitation of the Children of Ilúvatar.

The Innumerable Stars

|

| Varda, Queen of the Stars, described as "beautiful" by Tolkien which this artist has rightfully taken to mean, "having prominent cleavage and being all sparkly". |

And amid all the splendours of the World, its vast halls and spaces, and its wheeling fires, Ilúvatar chose a place for their habitation in the Deeps of Time and in the midst of the innumerable stars. And this habitation might seem a little thing to those who consider only the majesty of the Ainur, and not their terrible sharpness; as who should take the whole field of Arda for the foundation of a pillar and so raise it until the cone of its summit were more bitter than a needle; or who consider only the immeasurable vastness of the World, which still the Ainur are shaping, and not the minute precision to which they shape all things therein.

I fade the colour of the text here because it seems to be the description gets vaguer and weirder as it goes on. If it even has a meaning at all, I have no idea what it is. I surmise that either old J. R. R. had been at some quite special pipe-weed a bit too much that evening, or we have more intentional ambiguities. Indeed The Silmarillion does not describe Varda's creation of the first stars except very briefly in later passing. But it does describe how she creates additional stars for the birth of the Elves :

Then Varda went forth from the council, and she looked out from the height of Taniquetil, and beheld the darkness of Middle-earth beneath the innumerable stars, faint and far. Then she began a great labour, greatest of all the works of the Valar since their coming into Arda. She took the silver dews from the vats of Telperion, and therewith she made new stars and brighter against the coming of the Firstborn. And high in the north as a challenge to Melkor she set the crown of seven mighty stars to swing, Valacirca, the Sickle of the Valar and sign of doom.

The Elves become known as the Children of the Stars.

By the starlit mere of Cuiviénen, Water of Awakening, they rose from the sleep of Ilúvatar; and while they dwelt yet silent by Cuiviénen their eyes beheld first of all things the stars of heaven. Therefore they have ever loved the starlight, and have revered Varda Elentári above all the Valar.

The importance of the beauty of the stars, indestructible and incorruptible, remains a fixed constant right through to the final journey of the Hobbits into Mordor :

Far above the Ephel Du´ath in the West the night-sky was still dim and pale. There, peeping among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high up in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and hope returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty for ever beyond its reach.

So when Gandalf describes how the line of kings in Gondor failed :

Childless lords sat in aged halls musing on heraldry; in secret chambers withered men compounded strong elixirs, or in high cold towers asked questions of the stars.

We should not take this as meaning that Gondor fell from grace because of a pathological obsession with astronomy ! Indeed, Larsen describes in Unfinished Tales that there was at least one "good and wise" Númenórean king who was a competent astronomer. Given also the importance of starlight to the Elves, of moonlight to revealing dwarven letters, it would seem that "questions of the stars" only means "unanswerable and useless". Definitely not literally astronomy, then*.

* I know what you're thinking, and you can shut your ugly mouth.

Instead, the beauty of the stars is amongst the purest form of all in Tolkien's mythology. The "sickle" stars, presumably the Plough, prophesy Morgoth's ultimate downfall, but one particular "star" deserves special mention.

The Evening Star

When Morgoth has seemingly overrun all of Middle Earth, Eärendil, a mortal man, sails west with a Silmaril in a desperate attempt to seek the help of the Valar. And they answer him, which surprises Morgoth, who assumes he's already won :

For to him that is pitiless the deeds of pity are ever strange and beyond reckoning.

All the same, the divine nature of the Valar remains inscrutable. Yet in this instance they answer Eärendil's prayers and then some, sending forth in the War of Wrath the greatest host ever assembled that obliterates Morgoth and (nearly) all his servants. But Eärendil has ventured into a realm that is forbidden to mortals. Recognising that without their assistance all is lost, yet beholden to the doom of men, the Valar... compromise. Eärendil and his wife are granted a choice, to become immortal Elves or remain as mortals. They choose the former.

But they took Vingilot, and hallowed it, and bore it away through Valinor to the uttermost rim of the world; and there it passed through the Door of Night and was lifted up even into the oceans of heaven. Now fair and marvellous was that vessel made, and it was filled with a wavering flame, pure and bright; and Eärendil the Mariner sat at the helm, glistening with dust of elven-gems, and the Silmaril was bound upon his brow. Far he journeyed in that ship, even into the starless voids; but most often was he seen at morning or at evening, glimmering in sunrise or sunset, as he came back to Valinor from voyages beyond the confines of the world.

This is pretty obviously Venus. But whereas in Greco-Roman mythology Venus is a sexy oyster, Tolkien has something altogether more dramatic in mind. While "beauty" has strongly feminine connotations, this is not always the case. For the goodness of his deeds and his self-sacrifice, Eärendil too has this sort of true beauty which acts almost like a living force.

Or in other words, Tolkien has him fight a mountain-sized dragon.

|

| Some fan art, like this one, is a lot better than others. |

So sudden and ruinous was the onset of that dreadful fleet that the host of the Valar was driven back, for the coming of the dragons was with great thunder, and lightning, and a tempest of fire. But Eärendil came, shining with white flame, and about Vingilot were gathered all the great birds of heaven and Thorondor was their captain, and there was battle in the air all the day and through a dark night of doubt. Before the rising of the sun Eärendil slew Ancalagon the Black, the mightiest of the dragonhost, and cast him from the sky; and he fell upon the towers of Thangorodrim, and they were broken in his ruin.

There is simply no way to resolve this with what we know of Venus. According to Larsen's essay, Tolkien was careful to pay attention to such details as getting the correct phase of the Moon when referring to characters who are well-separated but with events happening at the same time. Yet just as the actual Moon is only a lump of rock, Venus is the closest place to hell that we've ever discovered. Sometimes Tolkien was wont to get petty, irrelevant details right, and sometimes happy to throw them all to the wind and write something based purely on emotion. The lights of the Moon and Venus feel like something pure and beautiful so Tolkien grants them corresponding roles, shaping their characters accordingly.

If Eärendil and his Silmaril are so potent as to become a star in the sky, something of this is captured by the Elves in the Phial of Galadriel. Though it isn't mentioned much, the Phial has the power to counter even the corruption of the One Ring :

Cold and hard it seemed as his grip closed on it: the phial of Galadriel, so long treasured, and almost forgotten till that hour. As he touched it, for a while all thought of the Ring was banished from his mind.

Later of course its power against Shelob is revealed more directly :

For a moment it glimmered, faint as a rising star struggling in heavy earthward mists, and then as its power waxed, and hope grew in Frodo’s mind, it began to burn, and kindled to a silver flame, a minute heart of dazzling light, as though Eärendil had himself come down from the high sunset paths with the last Silmaril upon his brow. The darkness receded from it, until it seemed to shine in the centre of a globe of airy crystal, and the hand that held it sparkled with white fire.

The effect of the Phial upon Shelob is very much like that of a cross to a vampire, warding off evil rather than actively injuring it. The Phial is of course only the faintest echo of a Silmaril, whose power was incomparably greater. Nevertheless, the power of the stars is as elsewhere in Tolkien the power of light against the dark. Evil flourishes in the darkness and is diminished by light and truth. While Eärendil with a full Silmaril can fight a vast and terrible dragon, Frodo's fight with a Shelob draws on the same principles : light against the dark, goodness against malevolence, the power of a star in miniature rendered against the horror of a creature from the darkest void. Tolkien sets the power of mythical, cosmological-scale symbolism into ordinary sized, seemingly everyday objects.

The Void : Ungoliant and Melkor

Of all the realms that can be described as in any sense "physical", the Void would seem to be much the largest. Beyond the Door of Night, beyond the Encircling Seas, lies the uttermost outer darkness. As a space it is little described. Arda is "sustained therein, but was not of it" which I take to mean something like how the world is suspended in (but not created from) space. It could also perhaps mean the Void has a wholly different nature to Arda, not just in its substance but in its emotional quality.

There is little information to draw on. References to the Void are few – all I can offer is a bad joke by Sabine Hossenfenlder, who notes that time is money, and money is the root of all evil. So I suppose the Void, being the abode of evil, must be subject to time at least... ahem.

Anyway, what few references to the Void are given are almost entirely related to demonic beings of terrible power. Of those, the uber-spider Ungoliant makes Shelob look like the sort of minor pest that even the most arachnophobic could safely escort outside in a jam jar. Her origin is kept mysterious but strongly hinted at :

Beneath the sheer walls of the mountains and the cold dark sea, the shadows were deepest and thickest in the world; and there in Avathar, secret and unknown, Ungoliant had made her abode. The Eldar knew not whence she came; but some have said that in ages long before she descended from the darkness that lies about Arda, when Melkor first looked down in envy upon the Kingdom of Manwë, and that in the beginning she was one of those that he corrupted to his service.

|

| Artwork by "bostonflows" from DeviantArt. |

This mysterious origin makes Ungoliant is one of the most intriguing creatures of all. Does she exist prior to Middle Earth or even Arda itself ? If so, why does Ilúvatar create her ? Or is his power and domain not actually limitless ? Does Melkor actually create her in some way ? Again, there are no more than the most tentative of hints :

He had gone often alone into the void places seeking the Imperishable Flame; for desire grew hot within him to bring into Being things of his own, and it seemed to him that Ilúvatar took no thought for the Void, and he was impatient of its emptiness. Yet he found not the Fire, for it is with Ilúvatar.

Which seems to mean that the "imperishable flame" (the Secret Fire that Gandalf refers to in his fight with the Balrog) is the soul, the mind, which only Eru can bestow. Melkor would clearly like to create entities all of his own, but is only ever able to corrupt and never to create. That said, some sort of creatures may have existed in the Void through the Song (coming up next), so she may have been originally good or at least neutral. In that case the Void itself would not be evil. There is nothing intrinsically bad about darkness, after all, the elves love the stars and these cannot be seen in the bright light of day. But darkness quickly becomes the domain of all evil things.

Even so, in contradiction to the weight of evidence that it's mind and intention that shape their surroundings in Arda, on these larger scales things might just be different. As Melkor slips from mere discontent to outright evil, he is described as "grown dark as the Night of the Void". Ungoliant spins webs of darkness and an "Unlight", which is not merely darkness as the absence of light, but darkness as a thing in itself. Perhaps this sort of true darkness is analogous to the "true beauty" possessed by some of the Elves, a thing which is itself a force itself in the world, or at least flows forth from creatures pure in heart – or in this case purely evil at heart. But even so, this sort of darkness still doesn't seem to make people evil : it remains the case that the truly evil can make the darkness rather than the other way around.

Ungoliant presents other, more pragmatic challenges. While Morgoth is the source of ultimate malice, Ungoliant at one point outgrows her master's strength and power. Given Morgoth's nature as one of the Ainur, second only to Eru (God) himself, this seems an impossibility. What apparently happens (according to Google) is that Morgoth over-exerts himself on his mission to destroy the Trees, while Ungoliant gains the power of the Silmarils. So this state of affairs is likely temporary, and Ungoliant's demise is not described. She appears to succumb to entirely natural causes, Tolkien blending myth and materialism once again : Melkor diminishing to Morgoth, Ungoliant to an otherworldly but mortal spider lurking in the Valley of Dreadful Death. Even the most formidable darkness cannot endure forever.

Morgoth himself is eventually cast out :

Morgoth himself the Valar thrust through the Door of Night beyond the Walls of the World, into the Timeless Void; and a guard is set for ever on those walls, and Eärendil keeps watch upon the ramparts of the sky. Yet the lies that Melkor, the mighty and accursed, Morgoth Bauglir, the Power of Terror and of Hate, sowed in the hearts of Elves and Men are a seed that does not die and cannot be destroyed; and ever and anon it sprouts anew, and will bear dark fruit even unto the latest days.

Just as Tolkien has aspects of totally evil and totally good, but more often things are far less clear, so it is here with the fundamental nature of the creatures themselves. Ungoliant seems to have arisen in the void but, though at one point surpassing her master in strength, eventually dies in mortality. Morgoth, though he gradually diminishes from an elemental force to a "dark Lord, tall and terrible" who can even be injured by ordinary blades, never wholly loses his Secret Fire. He remains at his core a supernatural Valar.

|

| Melkor in his elemental Valar form. |

Curiously, Melkor's evolution appears to be circular. He begins as an elemental, primordial symbol of hate, fear, evil and lies, then degrades into Morgoth, a powerful yet very physical being, a Dark Lord atop a Dark Throne. At the end, his defeat transforms him back into something more closely resembling his earlier incarnation. While the ending of the Quenta Silmarillion (above quote) could be read to mean only that Morgoth's lies persist his own demise, later in The Silmarillion it appears quite clear that Morgoth's will can still directly influence the minds residing in Middle Earth :

Thus it was that a shadow fell upon them: in which maybe the will of Morgoth was at work that still moved in the world. And the Númenóreans began to murmur, at first in their hearts, and then in open words, against the doom of Men, and most of all against the Ban which forbade them to sail into the West.

So the fulfilment of the myth may result in Morgoth as being potentially the source of all evil. Prior to his defeat there are numerous other cases of villainy which appears to have little enough to do with him, Elven "pride" (read : obstinate, bloody-minded, pig-headed self-righteous stubornness and stupidity) being a frequent source of disarray and degeneration. What happens afterwards is harder to say, with Sauron still at large until the end of the Third Age, and exactly how Morogth's will is able to transcend the Void, and to what degree, is not stated. But certainly there is a very clear implication here that the whole tale is ultimately an explanation, or at least a metaphor, for why evil exists in the world.

In The Beginning Was The Song

|

| AI-generated art, from here. |

We've seen already how songs and spells can shape the reality of Middle Earth : changing the seasons, overthrowing fortresses, bending the laws of chance, and contesting with the Dark Powers. In this final section we can see how such incantations can have much larger effects, back to the moment of Creation itself.

So at last we now turn to the final and most important example : the Song of Ilúvatar. Here at last is the answer to so many riddles, so many apparent contradictions. Tolkien, to his credit, did try to keep things self-consistent where necessary. This is a powerful aid to believability. But there are some aspects of Middle Earth which demand inconsistency and the utmost incompatibility with observable reality. Songs don't really bring down walls or bring forth flowers; words don't really affect the laws of chance... and of course the hell-planet Venus cannot really be a divine mariner who once brought down the greatest dragon in history.

The last is important. How can Tolkien be claim to writing a history of the world, even a mythological one, if it has such blatant untruths ? Only in part can this be explained through the myth giving way to the material. All the modern mountain ranges being formed by natural processes is not incompatible with the now-vanished ones of the distant past being created by other means. The problem is that the Sun and the Moon still exist, as of course do the stars, and we know what they are : it is not that we just can't see the divine pilots guiding them through the heavens, it's that observations are completely incompatible with Tolkien's explanations.

Okay, fine, we could say, "it's a metaphor". But that is super lame. We can do much better than that.

The Song provides the answer. The Silmarillion begins with an extended singing sequence in which Ilúvatar creates the Ainur as parts of himself :

There was Eru, the One, who in Arda is called Ilúvatar; and he made first the Ainur, the Holy Ones, that were the offspring of his thought, and they were with him before aught else was made... each comprehended only that part of the mind of Ilúvatar from which he came, and in the understanding of their brethren they grew but slowly.

Initially he teaches them only music and song, and for a while they have a lovely time all singing nicely together. But then Melkor decides that he's had it with all this music "like unto harps and lutes, and pipes and trumpets, and viols and organs" and decides he wants to play guitar instead. Or some such. Anyway, he decides to make his own disharmonious music "utterly at variance", which is "loud, and vain, and endlessly repeated; and it had little harmony, but rather a clamorous unison as of many trumpets braying upon a few notes."

So Ilúvatar responds with new and mightier music. Back and forth goes the cosmic jamming until at last Ilúvatar gets bored and tells them all to shut the hell up, bloody kids, I don't like music anyway...

Then Ilúvatar spoke, and he said: ‘Mighty are the Ainur, and mightiest among them is Melkor; but that he may know, and all the Ainur, that I am Ilúvatar, those things that ye have sung, I will show them forth, that ye may see what ye have done... And he showed to them a vision, giving to them sight where before was only hearing; and they saw a new World made visible before them, and it was globed amid the Void, and it was sustained therein, but was not of it. And as they looked and wondered this World began to unfold its history, and it seemed to them that it lived and grew. Ilúvatar said again: ‘Behold your Music! This is your minstrelsy; and each of you shall find contained herein, amid the design that I set before you, all those things which it may seem that he himself devised or added.’

Here is the crucial point. Arda is not made in response to the musical discord, it is the music from the very beginning. Eru and the Ainur (for that is their band name) made the world with song, but having only hearing, they know it only through sound. Everything that happens henceforth is only because the Ainur, who exist outside of time, are now bestowed with new senses with which to explore the fullness of their Creation.

The same is true of the Children of Ilúvatar. They are themselves part of the music. It is not that they have music or are moved by it, they are music.

Then again Ilúvatar arose, and the Ainur perceived that his countenance was stern; and he lifted up his right hand, and behold! a third theme grew amid the confusion, and it was unlike the others. For it seemed at first soft and sweet, a mere rippling of gentle sounds in delicate melodies; but it could not be quenched, and it took to itself power and profundity.

For the Children of Ilúvatar were conceived by him alone; and they came with the third theme, and were not in the theme which Ilúvatar propounded at the beginning, and none of the Ainur had part in their making.

But Melkor spoke to them in secret of Mortal Men, seeing how the silence of the Valar might be twisted to evil. Little he knew yet concerning Men, for engrossed with his own thought in the Music he had paid small heed to the Third Theme of Ilúvatar.

Men, music, and ultimately the Ainur themselves – all are ultimately the thoughts of Ilúvatar. Likewise, when Aulë creates the dwarves, Ilúvatar chastises him :

‘Why hast thou done this? Why dost thou attempt a thing which thou knowest is beyond thy power and thy authority? For thou hast from me as a gift thy own being only, and no more; and therefore the creatures of thy hand and mind can live only by that being, moving when thou thinkest to move them, and if thy thought be elsewhere, standing idle.’

This is idealism, the notion that all of physical reality is ultimately part of the mind of God. This is a complex point which necessitates a short philosophical digression.

In materialism, which is the common assumption nowadays, we take it that we perceive reality directly. If we see and touch a chair, we assume this tells us something about the base level of reality. But of course, observations can always be improved and extended. Materialism therefore has a problem not dissimilar to the "god of the gaps" argument, that in routinely filling in any and all unknowns with the label "god", certain sorts of theism are unconvincing because they're always shifting the goalposts. This is equally true for materialism : what's the base level ? Chairs ? Wood ? Molecules ? Atoms ? Electrons ? Strings ? Quantum foam ?

There's no easy answer. The original Greek notion of atoms as indivisible has long been refuted, and so far we have no evidence that anything truly indivisible and irreducible actually exists. This would make materialism no better than the sort of theism it claims to refute.

Idealism is an attempt to avoid this. It says that there is a base level of reality, however incomprehensible, and that it's God. The argument goes that explaining mind as the product of matter is nigh-on impossible, whereas it's obvious that we can all imagine matter at will. By extension, a sufficiently superior being could imagine an entire, self-consistent Universe.

This isn't the place to get into the merits of idealism, materialism, neutral monism and the like; Decoherency is chock-full of such posts anyway. Rather the important point is that Tolkienian cosmology is clearly idealism. The Ainur are created as thoughts of Eru, who in turn have thoughts of their own. These are initially expressed as music and later revealed through the full suite of sensory apparatus. The dwarves may be moved directly by the will of Aulë, but this too is fundamentally a part of the mind of Eru.

The songs of Lúthien and the Oath of the Noldor link back to this cosmic-scale aspect of the process. They draw on the forces which shape reality itself, sometimes only in apparently small ways but nevertheless always part of this much greater whole. That's how the magic works, according to Tolkien. This is what's going on when Gandalf fights the Balrog : the very forces that shape the universe are condensed into one old man and a fiery monster. No wonder it's dramatic as hell.

And that's how Eärendil can be both a hellish planet and a divine dragon-fighting mariner. His song has changed, but it remains the same song, unified in Eru. Music too is only analogy, something easier for the reader to grasp. We can readily understand how a musical piece can change yet have some core identity that remains the same, even if defining that identity is something far more challenging. So Tolkienian cosmology is a Grand Unified Theory of an altogether different sort than in modern physics, but it's of the same scale of thinking. In idealism, all religions and all fictions and all science alike can be true.

Of course, this raises once more that ugly question : why does an all-knowing, all-powerful, all-loving God allow evil things to happen, especially to good people ?

Under idealism, one interpretation is that he doesn't. There is no external reality to God, it's all his thoughts : the protagonists may seem distinct from each other but this is, in essence, a problem of coordinate systems. Eru doesn't prevent the fall of Númenór any more than we might prevent ourselves imagining its fall : from Eru's perspective Númenór is no more an external "thing" than it is, literally, to ourselves. We know it has no physical manifestation, it's all just make-believe, so we freely imagine any catastrophe occurring, no matter how bleak it would be if that were real.

So it is to Eru. He has precisely no more reason to stop the ascendancy of Sauron than we do.

Another way to look at it would be that it's all just music. Why would Eru prevent himself from creating a bad tune ? The reality of a bad tune and the wrath of Morgoth are equally valid from his point of view. He experiences all of it in his fullness, he knows the suffering occurring because it's also intrinsic to him. It's not that he creates everything, it's that he is everything. And if he wants to undo everything, he can. It takes no effort on his part at all.

The difficulty with this would be that Eru ought to know that his "Children" think themselves distinct and experience suffering and woe in a way that he himself does not. From their perspective they experience things differently than Eru himself. So alas, idealism does not wholly rescue this dilemma, and we have to fall back on the earlier argument that some things are just beyond our comprehension. Perhaps, for the story at least, leaving some mystery is essential.

Afterword : Conclusions and Comparisons

|

| I rather like this depiction of Valinor as somewhere less structured, with only hints of ordinary objects here and there. |

Well, that was fun. But what have we learned ?

Tolkien's work is utterly drenched in metaphor. He gets almost irate in in denying that The Lord of the Rings is allegorical, probably because it isn't. The entire work itself is metaphorical, reaching much deeper themes than merely retelling World War II but with Bar-dur as Hitler's fortress and orcs as Nazi soldiers. Rather it's an attempt at examining the nature of good and evil themselves, and if there are similarities – even symbolic ones – with actual events, this should only be because good and evil have distinct, recognisable tendencies and follow common patterns.

Not that things in Middle Earth are as black and white as they're sometimes made out to be. Far from it.

It was Sam's first view of a battle of Men against Men, and he did not like it much. He was glad that he could not see the dead face. He wondered what the man's name was and where he came from; and if he was really evil of heart, or what lies or threats had led him on the long march from his home; and if he would not really rather have stayed there in peace – all in a flash of thought which was quickly driven from his mind.

The tales aren't simple stories about some good people fighting some other, ugly-looking bad people. No. They're truly mythological in scope, pathetic fallacy applied to the grandest of scales, where mind and intent infuse the very substance of reality itself. From such petty details as the composition and size of the Fellowship* to the whole structure of the Universe, every aspect of Tolkien's creation is infused with this morality.

* I like the answer in the above link quite a lot. Help shall come from the weak indeed, with the Fellowship deliberately not being a military strike force... it's half-composed of people too small to even wield a full-size sword for a very good reason, because the story is a morality tale, a myth, not a realistic fiction merely set in a magical world but one fundamentally governed by different principles.

Only in part can we say that the appeal is due to the simplicity of good versus evil. There is that aspect to Tolkien, there are some characters who are virtue and evil incarnate, and this definitely plays its part. But there are also plenty of ambiguities, a richness of the spectrum filling everything in between the two extremes. Not every ill deed is evil, every dark thought the work of Melkor, nor is every good act rewarded or every injustice punished. Sometimes what seems like luck is really fate, but sometimes it's just pure happenstance. Being good or evil in Tolkien's world is not a guarantee or success or failure. True, evil ultimately fails. But along the way it has plenty of victories and countless innocents die in the process. The Lord of the Rings is a satisfying culmination of the tale but it is by no means representative of the whole history, much of which is altogether darker.

Tolkien goes much deeper than this popular but simplistic black-and-white depiction, examining the nature of good and evil and giving them physical embodiment. He casts his characters on a stage far bigger than themselves, giving them emotive effects on their surroundings, powers which affect reality in a way that reflect our own direct feelings of what it's like to experience emotions.

Discworld

Years ago I wrote a piece about the anthropic principle based on part of The Science of Discworld. Pratchett and his co-authors did an outstanding job of describing why this is not the slightest bit mysterious. And in the Discworld series, Pratchett has his characters as largely a product of their environment, the very essence of understanding the anthropic principle : we are the way we are because the Universe is the way it is. There's no mystery in that it seems fine-tuned to allow us to exist, and indeed if that were the case we ought to expect a massively larger fraction of the Universe to be habitable, rather than being confined to the most miniscule slice of warm damp air on a tiny nondescript little rock.

I suggest here that Tolkien, as a Catholic, does the exact opposite to Pratchett. He has characters shape the world around them by virtue of their morality : goodness begets beauty (not the other way around), evil causes corruption, decay and loathsomeness. For Pratchett, mind is just something that happens to matter in certain configurations under certain conditions. For Tolkien, mind is the essence of the universe, and sufficiently powerful minds can access deeper layers of reality and gain direct control over it. And this is even true of their respective cosmologies. As such, the Discworld is a small mote of magic in an otherwise familiar universe of stars and galaxies, whereas for Tolkien, Arda is a kernel of normality in a universe based more on morality than on physics.

Tolkien's idealism may reconcile how his stories can be at times self-contradictory without needing to say that he made a simple error, but it does not solve every moral conundrum. Some level of ambiguity is essential for myth-making, but some questions are beyond human understanding. But he does present some moral teachings : the importance of helping the weak, the need to do the right thing no matter the risk and no matter the cost, the solace in the certainty of change, the need for mercy, pity, and compassion – things which are incomprehensibly alien to the evil.

And above all, the importance of lies. Morgoth wins battles only rarely, if ever, through sheer military might. Yes, the size of his armies and the physical strength of his soldiers does matter, but far more important is treachery. Morgoth's greatest strength by far, the weapon he invariable reaches for ahead of all others, is deceit. In battle after battle, Tolkien gives Morgoth, the ultimate source of evil, the victory only because he sows discord among his foes, corrupting some critical element to his cause at an opportune moment. Frank Herbert probably said it most concisely but this is surely something Tolkien endorsed :

Respect for the truth comes close to being the basis for all morality.

Which is delightfully ironic when set in a world that is explicitly one of pure fiction and make-believe.

Westeros

As to Game of Thrones, nothing in the cosmology therein approaches the careful construction of Tolkien; so far as I can tell, it's just a bunch of cynical people who ride dragons and fuck each other repeatedly*. There's not much in the way of symbolism or deeper moral tales about the nature of good and evil, though there's plenty about the human condition.

* Though not, sadly, at the same time.

For this reason I'm of the opinion (rare on the internet !) that the ending to Thrones was absolutely fine. I realised recently that some people disagree not so much because they thought the ending was bad as because they thought the beginning was far superior to what it was, much as people dislike the Matrix sequels. "It was so deep !" they say, and I'm left thinking, "huh ?", because it wasn't. I mean, yeah, there are some hints of some deeper thoughts, what with the White Walkers and the coming of night, or the nature of reality if you jack yourself in, but honestly, they aren't much developed.

Which is why I wasn't at all surprised or disappointed by the franchises developing the way they did, because that's always how they were going to go. Sure, they've a smattering of insight, sometimes very interestingly so. But ultimately, Thrones especially, they're not about cosmology. It just doesn't matter to the story at all, which in Westeros is all about the people. For George R. R. Martin the background is only ever scenery; for Tolkien, it's every bit as essential as the characters themselves, a living, vital part of the story.

Don't misunderstand me here. When I say that Thrones is all about cynical people fucking, I also mean that it's masterpiece of that genre. Within its own framework, it's incredibly well-constructed. It's a complex tale with characters you genuinely hate to love (because they die horribly) and love to hate (because they're cunts). I will give Martin 10/10 on that score, and by no means do I underestimate the difficulty of this achievement. It's a genuinely magnificent mixture of genres, but a myth it ain't.

The greatness of true myth

In the end, Westeros is fiction, not myth. Tolkien reaches higher. Myth provides not just mere description but also explanation, couched in symbolism and ambiguity. Tolkien's application of pathetic fallacy to the cosmological scales certainly achieves this, and that's a far, far more precious accomplishment than anything as mundane as "realism". His characters are complex in their own ways and for their own reasons, but precisely because of the mythological intentions, they are and should not be as realistic as those of of other, more grounded works.

I have tried to present things here roughly backwards to the order Tolkien gives them in. He tells a story of a world crystallising from song to substance, from mythic to material. On a first reading, the early parts especially are hard to fathom. By telling the tale backwards I have tried to resolve some of the grosser ambiguities, to show the "bones of the world" that Tolkien – according to The Atlas – asked us not to see. And so we shouldn't, if we want to preserve the mystery that is so essential for a good myth. But sometimes, the temptation to try to peek behind the curtain is just too great.

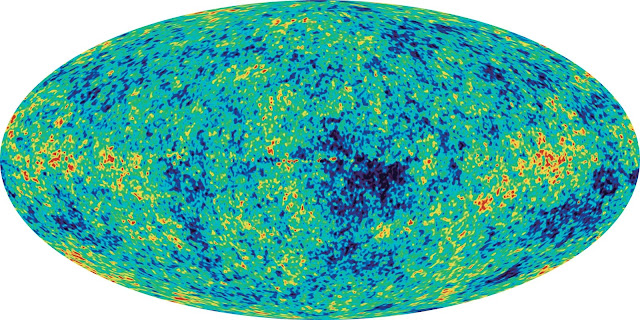

The final comparison I suppose I must make is modern cosmology. This, someone said, is "always on the edge of mysticism", which as an astronomer I cannot dispute. In terms of studying the evolution of the Universe and its general characteristics (the typical scale and structure of things, their ages, their likely future development) modern science is on very firm footing indeed. But when it comes back to the Creation event itself, there I think all our musings about creating particles from a vacuum, about whether physical laws are in some sense real things or merely descriptions of stuff that happens... all of that does stray into the mystical.

But perhaps not the mythical. Myth, I've said, has to provide an explanation, it has to apply at scale, it has to involve minds, and it has to contain ambiguity. Scientific cosmology really only does and can do the first two of these – if it started positing that the Universe was the result of intelligence or avoided quantitative rigour then it wouldn't be scientific at all. When we get back to the singularity, however (be that whether the Universe was at some point infinitely small or has existed forever, with both types of infinity being a sort of singularity), we find our capabilities collide head-on with reality. We meet something our language and perhaps our most basic mental capacities are unable to grasp, and so we reach inevitably for myth.

I said back in the introduction that Tolkien himself I do not hold faultless. And it must be said that he was somewhat hypocritical, in that his works were chock-full of revision after revision but he himself was an extreme purist when it came to adaptations changing even the most petty and irrelevant of details. But my analysis has been an attempt not to understand what Tolkien himself thought, but the effect his work had on me. That, I think, is the key part of the ambiguity of myth. It requires the reader to fill in part of the details with their own emotions, to take us to places that precise description cannot reach.

Pratchett said that human beings need fantasy to be human, that we need to believe things which aren't true. But perhaps more than needing to believe things in manifest contradiction to the observable facts, we need to believe things which no amount of observation can ever capture. We need fantasy to understand ourselves, to try and give shape to the unseen, feelings made flesh. And that is why, far from God being dead, in this modern scientific age of quantification and rationality, myth still, and will ever, continues to endure.