It's the rallying cry of the pseudoscientist : "Some even call me mad.... And why ? Because I dared to dream of my own race of atomic monsters, atomic supermen! with octagonal shaped bodies that suck blood..."

But it's also one of those very well-known facts that geniuses can come up with seemingly delusional ideas that are later recognised to be revolutionary breakthroughs. It's so well-known that there's even a catchy song about it.

Oh, I wasn't a bit concerned

For from hist'ry I had learned

How many, many times the worm had turned

They all laughed at Christopher Columbus when he said the world was round

They all laughed when Edison recorded sound

They all laughed at Wilbur and his brother when they said that man could fly

They told Marconi wireless was a phony, it's the same old cry

To an extent, this idea is useful - we should always remember that new ideas haven't always been well-received. Skeptical inquiry, attacking an idea to see if it survives, is precisely how the scientific consensus is established. But what some would have you believe, as in the above meme, is that all great revolutionaries were derided as loonies and crackpots - that their "fringe" ideas will one day be recognised for their true greatness and the establishment will have to eat a large helping of humble pie.

But did they really say all these true geniuses were mad ? Who said it ? Why ? How long did they persist before admitting they were wrong ? As far as the, "they said I was mad, but I'll show them !" crowd are concerned, these little details could be anything but. As we've seen, revolutions triggered entirely by lone geniuses are largely - if not entirely - mythical; while there is certainly a germ of truth here, the reality is much more nuanced. Geniuses don't make all their breakthroughs by themselves, revolutions don't really go from zero to paradigm shift overnight and their impact isn't immediately understood.

But did they really say all these true geniuses were mad ? Who said it ? Why ? How long did they persist before admitting they were wrong ? As far as the, "they said I was mad, but I'll show them !" crowd are concerned, these little details could be anything but. As we've seen, revolutions triggered entirely by lone geniuses are largely - if not entirely - mythical; while there is certainly a germ of truth here, the reality is much more nuanced. Geniuses don't make all their breakthroughs by themselves, revolutions don't really go from zero to paradigm shift overnight and their impact isn't immediately understood.

The myth of the lone genius makes for inspiring stories. Work hard, stay the course, and maybe you too can be the next Einstein. You're not wrong, everyone else is wrong. They're laughing at you ? Well, they did the same to Edison/Columbus/Wegener/etc. too, so that means you're probably a misunderstood genius as well. They're all just too proud to admit that they're wrong. Which is motivational and encouraging, but often it's also damaging and misleading.

|

| And I'm not a historian, so treat the rest of this post with great caution and do let me know if you spot any mistakes. |

Of course, scientific beliefs change with time because they're evidence-based and provisional. Few people ever suspect that we've got science well and truly licked, though, inevitably, there are always some people convinced that some particular aspect is completely done and dusted which later turns out to be fundamentally wrong. The question is one of degree : to what extent does the scientific community* act with an attitude of denial rather than skepticism when a new idea comes along ? Is there any truth to this at all, or is it a pure fiction invented by pseudoscientists to justify their half-baked quackery ?

* It's one thing for the lay public to laugh at ideas, and quite another for qualified experts. As the saying goes, the more you research, the crazier your sound to ignorant people. So in this case I'm going to largely ignore public opinion and concentrate only on the mood of the experts.

* It's one thing for the lay public to laugh at ideas, and quite another for qualified experts. As the saying goes, the more you research, the crazier your sound to ignorant people. So in this case I'm going to largely ignore public opinion and concentrate only on the mood of the experts.

This is a somewhat subtle notion which can't be readily quantified. First, there's a fine line between rational skepticism ("using what we know currently, let's try and disprove this idea") and denialism ("we already know enough to say that this is definitely not true and nothing will ever change that"). Even apparent deniers are sometimes just full of bluster and can end up changing their minds if sufficiently strong evidence is presented; true skeptics can sometimes be entirely rational but examine every minor detail to a ludicrous degree before accepting a new idea. Attitude is not something you can put a number on, so we'll have to look at - wherever possible - what it was people actually said.

Second, our brains are not Bayesian nets - we don't update our ideas immediately when new evidence is presented. It takes a while for entrenched beliefs to shift. It's one thing to yell, "you crazy loon !" at someone and then five minutes later say, "whoops, I was wrong, how about that", and quite another to engage in a systematic campaign of denial for a few decades. The thing is that even staunch denialism does make sense in some circumstances : at one point there was little or no evidence for a round Earth, so saying, "I think it's round, because the magic pixie told me so" should have been met with denial. Repeating the claim that the magic pixie said so wouldn't have made it any more likely to be correct.

So it's very important to consider what people were saying, how long they were saying it for, and whether they changed their minds for good reasons. All this already makes the notion that all good ideas were once dismissed as crazy to seem like, potentially, a gross over-simplification. All new ideas are rightly considered controversial - almost by definition - but are revolutionary ideas really dismissed as heresy ? Does the establishment really label all dissenters as cranks and crackpots, or just the genuine loonies ?

But did they even do that ? Did they really laugh at all these popular examples pseudoscientists drag up as examples of mainstream science refusing to listen to reason ? Were they treated as merely controversial - which is absolutely the proper way of doing science - or was there a more sinister form of dogmatism at work ? This is a topic I've covered many times before, but today I'll try a new approach of examining specific historical cases. I'll start with those in the first meme and move on to some suggested in a comment and add a few of my own for good measure.

1) Columbus

No, no, no, no, no ! This is a complete and total myth, which, shamefully, is still taught to schoolchildren today. No medieval scholar believed the Earth was flat - if you want to find a time when this belief was widespread among academia, you probably have to go back to a time before classical Greece. Not only that, but even Columbus' crew weren't afraid of such nonsense - indeed as sailors, they would have seen the classic proof that the Earth is round by watching ships slowly disappear below the horizon. This is one of the most pernicious of all the "medieval Christian stupidity" myths that has absolutely no basis in fact.

Well... almost none. It's of course possible that the common people had a different view from scholars and sailors, but the idea that the experts were all given a right good kicking up the intellectual backside by plucky Columbus is pure bunk.

EDIT : Interesting note in a comment - Columbus struggled to drum up funding because he was using an inaccurate value for the circumference of the Earth, which was too small. If he'd stated the correct value - which was known at the time - he'd probably never have gone, since he never could have survived such a long journey across the (apparently) open sea. So one may claim that Columbus was derided by experts but for perfectly sensible reasons - indeed, he never did reach India. No-one could possibly have known that America would get in the way and ruin the trip.

2) Bruno

We've met Bruno before and seen how his case has been twisted to fit an anti-religion agenda, whereas in fact things are much more complicated. At best, he appears to be an extremely rare case of a victim of an anti-science attitude among the Church. In all probability - there's some controversy over what he was actually burned for - it's far more likely that he was burned for a combination of a very bad attitude, plagiarising, and preaching unrelated religious heresies. In any case, he had absolutely no evidence for many of his beliefs, and though some of them did turn out to be correct, he was essentially little more than a mystic and a charlatan - hardly a martyr for science !

As I've said before, it's fine to use a magic pixie to give you ideas, but if your pixie doesn't tell you empirical ways to test those ideas, you need a better scientific advisor. More to the point, if your magic pixie tells you something that turns out to be correct, that does not necessarily vindicate your pixie's supernatural scientific techniques or even prove the existence of your supposed fairy godscientist. You can have ideas for whatever reason you like, but you have to test them in an objective, measurable, repeatable way. Bruno did nothing of the sort - right or wrong, he was still a crazy.

Obviously burning Bruno was a step that was a teensy-weensy bit too far, but if his ideas hadn't been dismissed, we'd also have to put up with people going on about planets made of shrubs and Nazi flying saucers living inside the hollow Sun... oh, God. I just made the fatal mistake of Googling that in case it was a genuine crackpot theory, and it is.

3) The Wright Brothers

This is rather outside my specialist area but it's very difficult to believe that they were "ridiculed and condemned for believing a machine could fly". In 1903 human flight had been a reality for at least 120 years since the Montgolfier brothers launched a balloon; there are reports of the Chinese using kites to lift people in the sixth century A.D. As for machines, the first steerable airships are reported from the late 18th century, while the first engine-powered airship took flight in 1852. Zepplins were already a thing by the time the Wright brothers were flying, and even the powered aeroplane didn't just come out of nowhere - experiments had been underway for many decades (and gliders for even longer). So the idea that the Wright brothers would have been ridiculed merely for proposing that a machine could fly is itself ridiculous. Yeah, I know, it's a meme, and memes are simplifications. But it's still wrong.

On the other hand, one can see why there might be rather more skepticism regarding the idea that heavier-than-air flight was the future, or that Wright's specific machine was such a wonderful revolution. Their first machines were extremely crude, it was not easy to envisage them being scaled up to anything resembling modern jet airliners. Certainly other experimenters were derided in the popular press due to catastrophic failures, yet even the then-famous Samuel Langely had managed to procure substantial government funding for his efforts. While it's true that the still-famous Lord Kelvin was very skeptical about flying machines*, a widespread opinion among experts that this was impossible looks rather unlikely.

* However I cannot find any reliable confirmation that he really said, "heavier than air flight is impossible", as is often quoted. That would have meant he denied the existence of birds, which is stupid. What he actually said was (somewhat) more moderate, albeit still strongly skeptical.

About the closest thing I can find to this is a quote from Scientific American, which is remarkably similar to a ClickHole article :

So although there might have been an element of media denial, it doesn't look like that was borne out in the opinion of mainstream experts. I couldn't find any evidence of the Wright brothers being ridiculed by aeronautical experts, and even if they were, that could easily be attributed to them being overly-secretive - and it was, of course, dramatically and totally overturned in the space of a few short years. And if you Google, "Wright brothers ridiculed", you find results dominated by pseudoscience and related posts : "they were ridiculed" appears to be something people say to justify their silly theories, not something that actually happened.

4) Vesalius

I know even less about this dude than the Wright brothers, so this is limited to purely internet-based fact checking. Vesalius was a 16th century anatomist who was among the first to re-check the claims of the Greek physician Galen, who, it's fair to say, was treated quite wrongly as an authority beyond question. Certainly dogmatic thinking is a very real thing, of which the near-veneration of Galen is akin to that of Aristotle or Ptolemy. But what happened when Vesalius dared challenge the thousand-year gospel of Galen ?

It seems that reactions were somewhat mixed. He did suffer attacks for some of his discoveries, but I could find only one source claiming that he was denounced as a "heretic and imposter" (an odd choice of word - who was he impersonating ?), which is a self-confessed unorthodox book claiming that there's a very simple cure for cancer. The author also denies HIV is a disease and that chemtrails are actually a thing, for god's sake. Similarly, this very clearly biased website implies that the Church was very strongly opposed to dissections and that Vesalius went on a pilgrimage to avoid the Inquisition, which is now refuted by most scholars.

More reliable sources note that while he was subject to some vicious, personal individual attacks for taking on Galen ("the insolent and ignorant slanderer who… treacherously attacked his teachers with violent mendacity and time and time again distorted the truth of nature"), unauthorised copies of his books became available extremely quickly - hardly a sign of ridicule !

So my naive verdict would be that this is again largely a myth. You can always find someone to ridicule anything, just like you always can find anyone to agree with anything. There seems to be little or no evidence that Vesalius suffered anything like widespread ridicule or accusations of heresy, though it's worth noting that dogmatic thinking was definitely occurring even so.

5) Harvey

Another web-based fact checking exercise. At last, this one appears to have a grain of truth in it. Harvey was a highly respected physician who attended to no less than two kings , but he did lose some support due to his findings on blood circulation. Exactly how much is difficult to say, but it seems something of a stretch to say he was "disgraced" as a physician. He never lost his head or even his job, and though support for his findings was mixed (being rather more popular in his native England), he seems to have gradually won more converts within his own lifetime. Even so, he was not happy with the treatment he received from some of his detractors :

6) Galileo

Everyone's standard go-to scientist for "proof" of the dogmatic evils of the Catholic Church. We've met him before, and it seems pretty clear to most modern historians that the case is rather more complicated than science vs. religion. However there was an element of this (much more so than with Bruno), particularly due to an unusually strict Inquisitor, but equally, his evidence for some claims was just not all that good. The idea of heliocentricism was genuinely scientifically controversial at the time - even Galileo himself implicitly acknowledged this, publishing ideas as a series of fictional debates (albeit one-sided ones).

Galileo did not shy away from courting controversy on other issues besides the more famous heliocentrism (read that link for a full description of how and why it became as controversial as it did - Galileo himself is probably partially to blame*). But was he widely dismissed as a crackpot ? There seems to be little evidence of that, though undoubtedly his ideas on heliocentrism were controversial. A perhaps appropriate modern analogy might be Fred Hoyle, who more or less everyone acknowledges as a great scientist despite being wrong about a lot of things. Galileo was right, but he didn't really have the evidence to convince everyone - though again, there certainly was an element of dogmatic religious thinking going on here.

* Galileo was a brilliant but complex man. Reportedly he liked engaging in "robust conversations" with anyone who disagreed with him, Church or no. For example although he corresponded with Kepler, he apparently mocked his (correct) idea about the Moon being responsible for tides, and just never responded when Kepler suggested that planetary orbits might be elliptical. On the other hand, this didn't stop him from recommending Kepler for a mathematics position ! This attitude, as I can attest from first-hand experience, is not so uncommon today - some professors only respect you once you start to fight back.

As far as the meme goes, Galileo was placed under house arrest, which is a bit different to being thrown in prison. Galileo didn't invent the idea of heliocentrism, nor were his predecessors even arrested for their ideas. So as to the direct implication of the meme that Galileo was arrested because heliocentrism was not tolerated - well it's just not that simple.

7) Everything That Can Be Invented...

Not exactly a case of an individual having a crazy-but-true theory, but still a classic example of scientific hubris. This popular quoteable quote does seem to be an urban legend - apparently originating not from a patent commissioner, but a joke in an 1899 issue of Punch magazine. But what of the other widely-reported idea that scientists near the end of the 19th century thought they'd basically got everything licked ?

There may be some truth to this. Wikipedia states that, in the last years of the 19th century, no-one would have believed that physics was not all it was cracked up to be :

8) Invention of Lasers

While the laser resulted in a Nobel prize for its inventors within just ten years, it does seem to have been met with very strong skepticism from extremely qualified experts. But not for very long. Wikipedia cites that one of the inventors was told it was impossible by scientists no less presitigious than Neils Bohr. Yet reading the source material, it's clear that it's hardly the case that they were widely dismissed as crackpots :

9) Radio Waves From Spaaaaaace !

Ummm.... no ? Plenty of scientists were expecting to find radio waves from space decades before this actually happened, though the precise apparatus required wasn't properly understood. However, it's true that the discovery of the ionosphere discouraged efforts, as it blocks long-wavelength radiation. It's also true that the eventual detection was serendipitous and didn't exactly have people dancing in the streets. Jansky himself did no further research* into radio astronomy, but the first dedicated radio telescope was built just a few years later. Even WWII didn't stop research completely, though things didn't really pick up until the 1950s.

* Jansky was working for a private company and there wasn't any obvious commercial application of his discovery. Things would almost certainly had been different if he'd been working at a university.

I can't find any evidence that anyone trying to start doing radio astronomy was ever ridiculed. I suppose it could be argued that people stopped looking for radio waves after the discovery of the ionosphere, but a) that's a bit different from calling people names and b) it could also have just been due to the technological limitations of the time (detecting emission at different wavelengths can require radically different instruments). At most, you could make a plausible argument that it took a while until the importance of radio astronomy was widely accepted.

10) Magnetic Fields in Galaxies

Given that so many of the fundamental breakthroughs in electromagnetism were made in the 19th century, it comes as no surprise to learn that efforts to detect magnetic fields in space were underway in the early 20th century. This, however, is much the most difficult of the topics to research - it's important, but nowhere near as revolutionary as the other topics. And unfortunately it's dominated by the "Electric Universe" crew. Unlike the political institution, this EU is not well-regarded in the scientific community - long story short, it's considered to be just plain wrong. EU advocates are essentially confined only to the internet, where they make all the usual, "they said I was mad ! scientists are dogmatic !" claims of any group of true believers the establishment has discredited.

I don't particularly want to go in to that. It's possibly something - eventually - for a future post, but right now we need to cut to the chase. The problem is that the discovery of a galactic-wide magnetic field was predicted by Hannes Alfvén in 1937, who is basically idolised by the EU community in much the same way that Tesla and Zwicky are sometimes worshipped by their fanboys elsewhere on the internet. This means that researching this comes up with all manner of websites bluntly stating things that just aren't true or can't be verified, e.g. that Alfvén predicted the filamentary structure of the Universe in 1963 (there's no record of this on ADS), that for some reason this "confounded" (well at least it's not "baffled"....) astrophysicists in 1991 (it was actually known by the early 1980's), that this "added to the woes of Big Bang cosmology" (it does nothing of the bloody sort !), or that mainstream astronomers think that black holes cause galaxies to spin - which we just don't, because that's stupid.

The only thing I can reliably determine here is that Alfvén was indeed a controversial figure. He won scholarships, professorships, and ultimately the Nobel prize - hardly the sign of being regarded as a crackpot - yet apparently he had difficulty publishing papers. Certainly his proposed alternative cosmology is derided as mad, because it is. Similarly, Halton Arp was both widely respected for his Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies but condemned for his bizarre ideas about redshift. But did Alfvén face ridicule specifically for proposing that galaxies have magnetic fields ? About the only thing I can find is that it was "generally disregarded" and, shamefully, when the fields were discovered his original proposal wasn't acknowledged. Alas, getting to the bottom of this requires a true science historian and a genuine expert in plasma physics.

11) You Will Not Go To Space Today

Rockets have been in use for more than 700 years, but it wasn't until the 20th century that they received any amount of serious theoretical and practical attention from scientists. American rocket pioneer Robert Goddard was, if not ridiculed by the establishment, certainly not taken entirely seriously and was indeed lambasted in the press. The problem, perhaps, was that for the bulk of their already long history, rockets had been pretty crappy - powerful and terrifying, but wildly inaccurate. Using them to travel anywhere must have seemed like trying to ride a tiger.

Goddard seems to have been able but reluctant to publish, at least in part due to trepidation about how this would be received by the scientific community. However, the media attacks were vicious and unjustified, famously (and totally erroneously) claiming that rockets can't work in space*. No scientist would ever have said such nonsense (Goddard published rebuttals in scientific journals), though there are plenty of idiots still claiming such tripe today, but dealing with a hostile media appears to have sent Goddard into hiding. Things did change in his lifetime, but slowly. It perhaps didn't help matters that one of the other great pioneers of American rocketry was an out-and-out fruitcake.

* Even worse was their assertion of Einstein and colleagues as a scientific elite authority - urrrgh !

Unfortunately, while it's trivial to find out what the ignorant press were saying, it's nigh-on impossible to find out what scientists were saying. Many articles mention criticism from other scientists, but actual quotes appear to be non-existent. Clearly the responses must have been mixed, because he was publishing papers and securing patents and funding (albeit at a modest level). Goddard appears to have been naturally shy, but dealing with criticism is fundamental to the scientific method - given the track record of rockets at that point, harsh criticism might well be expected.

Goddard produced a memorable quote to a reporter :

12) Death From Above

That rocks from space occasionally collide with the Earth is now such an absolute certainty that it's almost difficult to believe that at one point, the scientific establishment was having none of it. The problem is that impacts are so rare that it's incredibly unlikely a scientist would just happen to be in the right place at just the right time to witness such an event. Terrestrial meteor craters are not always easy to spot or to distinguish from volcanic craters, similarly volcanoes were invoked to explain lunar craters (never mind the bizarre alternative pseudoscientific theory of "world ice"). Meteor showers were once explained as being the results of volcanic explosions or even an atmospheric phenomena, until eventually a meteorite impact had such a large number of witnesses that it couldn't be discounted.

It's worth remembering that at the time, the existence of the asteroid belt was utterly unknown. Theories of the formation of the Solar System were still in their infancy (perhaps they still are); no-one could reliably predict the existence of countless small rocks floating around in space. In contrast, volcanoes were definitely a known thing, as was lightning. So a terrestrial/atmospheric origin was much more likely given the evidence at the time. Thomas Jefferson even said that he'd rather believe that a professor would lie than the idea that "stones would fall from heaven".

There doesn't seem to have been a single leading figure in the early days of the extraterrestrial meteor hypothesis - it was a slow, gradual accumulation of evidence. Although there were those who ridiculed the idea, overall, it seems to have been little more than ordinary, entirely legitimate skepticism. Widespread ridicule, once again, does not seem to have been much of a thing, and in the worst case it quickly faded as the evidence mounted.

13) The Big Bang

Oh, delicious irony. Pseudoscientists today just love to try and debunk the Big Bang, claiming (as mainstream scientists had once done) that it's nothing more than stealth Creationism. Yet it took many decades before the Big Bang was established as the mainstream viewpoint, and during that time things did indeed get ugly - with Fred Hoyle famously coining the very term, "Big Bang" as a pithy way to dismiss it*. Nowadays the Steady State theory belongs firmly in the realm of pseudoscience, though an unsteady state model might be feasible if you have an inexplicable desperation to avoid a "creation" event.

* He also said, "The reason why scientists like the "big bang" is because they are overshadowed by the Book of Genesis. It is deep within the psyche of most scientists to believe in the first page of Genesis", while simultaneously advocating something approaching the strong anthropic principle. It's fair to say that his views on science and religion were anything but simple.

So indeed the worm has decisively turned on this one. But was mainstream science being overly-dismissive of the idea ? Initially, probably not - if the only evidence was galaxy redshifts, it made sense to consider other options. But as the evidence gathered (an unavoidably slow process), the theory won more converts. There was certainly a strong element of prominent, public denial and even ridicule - but any argument that the main community had a persistent adherence to the older order doesn't stand up. Moreover, the instigator of the idea - Georges Lemaître - was on speaking terms with Einstein and Eddington, so the reception was very much "mixed", with not much hint of any one-sided derision of crackpottery.

14) Wegener

Alfred Wegener is someone I've long proposed should have a law akin to the more famous Godwin's Law - just as anyone mentioning Hitler instantly loses the argument, so should anyone comparing their theory to Wegener's ideas on continental drift. It's true that he was vindicated long after his death after being almost completely dismissed during his lifetime. It's also true that, although not a geologist, he presented a good deal of evidence in support of his theory.

Wegener appears to have been misunderstood for a variety of reasons. On the more positive side, he didn't speak good English so didn't defend his theory when aspects of it were misunderstood. He also didn't produce a satisfactory mechanism to explain it (though he did speculate along very promising lines), which for an idea this radical was a huge disadvantage. And other explanations seemed largely able to deal with the known problems without recourse to such a novel idea. The more negative aspect is that Wegener wasn't a geologist, and scientists don't always appreciate experts in other fields (i.e. non-experts) contradicting their ideas. The problem is that there's a very good reason for that : the non-experts are usually wrong !

Wegener, like Hitler, is an extreme case - it doesn't make a lot of sense to compare fringe ideas to Wegener any more than you should compare the EU to Nazi Germany. It's true that unlike Bruno, he had good evidence for his ideas - but he still had little clue about the mechanism. And while he was mocked for continental drift, it doesn't seem to have done his main career (as a polar researcher) much harm. Which is not so uncommon as you might think.

Conclusions

Scientific credibility, like most things, is a spectrum - ranging from mathematical certainties to absolute drivel. There isn't always a clear line between mainstream science, fringe ideas, and abject pseudoscience - but it's usually possible to differentiate between promising ideas and really stupid ones. By and large, ideas which have been extensively labelled by experts for prolonged periods as mad have tended to actually be mad.

Of course, science is a human endeavour subject to all the usual flaws, despite the many safeguards in place to minimise them. Yet in general, if you have to resort to saying, "I'll be vindicated one day !" then you've basically admitted you don't have enough evidence to support your claim. True, occasionally such claims are borne out - but the road of scientific progress is littered the corpses of far more such ideas that were simply wrong. Saying, "the establishment got it wrong once" in absolutely no way whatsoever implies that your terrible idea is somehow actually a good idea.

It's all very well to point out that the public and the media have unleashed scathing criticism on some ideas - that's pretty common, you're on very firm ground with that one. And not all that unexpected either, since the lay public are by definition not as qualified as experts. It's also useful to remember not to pay too much attention to the slings and arrows, because reality doesn't care what people think of it.

But if you want to claim that all the experts just aren't listening, the popular historical examples suggest that you're on very thin ice indeed. Many of these appear not to have happened at all - the experts never dismissed Columbus or the Wright brothers. Others are more complicated - some experts did react strongly, only to retract their objections later (in some cases in a matter of minutes), while often there's a strong element of the historian's fallacy at work : often the evidence just wasn't good enough, and the dismissal was nothing more than standard skeptical inquiry without which science would never get anywhere.

It's really, really hard to find any clear examples of widespread, prolonged expert dismissal that flies in the face of the evidence. Certainly individuals are wholly capable of this (Fred Hoyle being the classic example), while widespread prolonged dismissal by the press happens quite often (e.g. Robert Goddard, climate change). Wegener probably comes closest to this, but even he didn't really have a good mechanism to explain continental drift, so it's not quite the same as if the evidence was being ignored. As for Alfvén, that's a possibility - the problem is that since his sainthood by the Electric Universe lot, it's damned hard to find anything about him that isn't unequivocally biased. Possibly, like Wegener, he never made a determined effort to convince his detractors, or possibly his good ideas were drowned out by his unnecessarily radical alternative cosmology.

I hate this quote. The thing about skepticism is that you have to fight back. That's part of the point : to provoke debate, not suppress it. If, like Goddard and Wegener, you don't really try, no-one's ever going to believe you. Which is an unfortunate reality for those not prepared to fight their corner. You can have an idea as crazy as you like, but if you don't have evidence to support it and you don't try to defend it, there's no reason to expect people to believe it. If people dismiss you and you still believe it, keep trying to get new evidence. But if absolutely everyone is still against you, perhaps you're, well, just wrong ?

Pseudoscientists love to play the, "they laughed at all these guys" card. As we've seen, that's an over-simplification at best, and at worst it's just not true. It's also an admission of weak evidence, which means there's little reason to prefer their ideas to any others. Of course all new ideas are treated with skepticism and are often controversial, but that's trivial and hardly worth mentioning. But, as far as I can tell, the evidence for systematic, widespread expert denial appears to be very thin indeed. Even when dogmatic thinking was occurring, such as with the veneration of Galen and Aristotle*, once evidence began to be presented, opinions changed.

* It's very unlikely that such authority figures could dominate science again. Most genuine experts are well aware that even the leading names in their fields make mistakes, because it wouldn't be research if you knew what they were doing. Some people carry more weight than others, but no-one is beyond question. However for other ways in which freedom of thought can be stifled in modern academia, see this.

Still, I want to end on a a couple of caveats. First, a few months ago I came across an article which looked to be the Platonic ideal for the pseudoscientists : claims that mainstream academia had not only dismissed ideas of animal consciousness/intelligence for many years, but also dismissed researchers from their posts for going against the mainstream. It appeared to be well-cited and with numerous examples. Despite a great deal of searching I've been unable to find it again. If anyone out there has any idea which article I'm talking about, do get in touch.

Second though, I'm not a historian, and I found quite a lot of "absence of evidence" - people claim there was scientific criticism, but the original statements aren't available. So the truth of the matter might not be quite as one-sided as it appears. Still the point remains that it's important to understand who was doing the ridiculing, for how long, and whether they changed their mind. It's not enough to simply declare, "they said Columbus was mad !". For this to justify fringe ideas, their has to be a broad similarity, not a superficial one : a consistent, widespread dismissal of clear evidence by mainstream experts. As far as I can tell, this is a very rare thing indeed, whereas the failure of pseudoscience appears to be something close to absolute. The truth is like a lion in one important regard : it's big and fluffy and sometimes it bites you. Or something.

Even with these caveats I'm surprised at the strength of this result, the possible animal intelligence article notwithstanding. Although strongly-worded debates are part and parcel of changing the consensus, still, I expected to find at least a few cases where the bulk of the establishment had persistently ignored or condemned strong evidence - conservative thinking is an entirely natural human tendency. Yet there appears to be not a single case of someone initially seen as a crank who presented good evidence still being widely treated as a crank, even in the Middle Ages when science, faith and mysticism were intimately connected. Curiosity, open-mindedness, and a simple desire to learn are not so easy to suppress, nor, though it undoubtedly does happen, do either religious or scientific institutions inevitably act to enforce dogma. Maybe there's hope for us yet.

Second, our brains are not Bayesian nets - we don't update our ideas immediately when new evidence is presented. It takes a while for entrenched beliefs to shift. It's one thing to yell, "you crazy loon !" at someone and then five minutes later say, "whoops, I was wrong, how about that", and quite another to engage in a systematic campaign of denial for a few decades. The thing is that even staunch denialism does make sense in some circumstances : at one point there was little or no evidence for a round Earth, so saying, "I think it's round, because the magic pixie told me so" should have been met with denial. Repeating the claim that the magic pixie said so wouldn't have made it any more likely to be correct.

So it's very important to consider what people were saying, how long they were saying it for, and whether they changed their minds for good reasons. All this already makes the notion that all good ideas were once dismissed as crazy to seem like, potentially, a gross over-simplification. All new ideas are rightly considered controversial - almost by definition - but are revolutionary ideas really dismissed as heresy ? Does the establishment really label all dissenters as cranks and crackpots, or just the genuine loonies ?

But did they even do that ? Did they really laugh at all these popular examples pseudoscientists drag up as examples of mainstream science refusing to listen to reason ? Were they treated as merely controversial - which is absolutely the proper way of doing science - or was there a more sinister form of dogmatism at work ? This is a topic I've covered many times before, but today I'll try a new approach of examining specific historical cases. I'll start with those in the first meme and move on to some suggested in a comment and add a few of my own for good measure.

1) Columbus

No, no, no, no, no ! This is a complete and total myth, which, shamefully, is still taught to schoolchildren today. No medieval scholar believed the Earth was flat - if you want to find a time when this belief was widespread among academia, you probably have to go back to a time before classical Greece. Not only that, but even Columbus' crew weren't afraid of such nonsense - indeed as sailors, they would have seen the classic proof that the Earth is round by watching ships slowly disappear below the horizon. This is one of the most pernicious of all the "medieval Christian stupidity" myths that has absolutely no basis in fact.

Well... almost none. It's of course possible that the common people had a different view from scholars and sailors, but the idea that the experts were all given a right good kicking up the intellectual backside by plucky Columbus is pure bunk.

EDIT : Interesting note in a comment - Columbus struggled to drum up funding because he was using an inaccurate value for the circumference of the Earth, which was too small. If he'd stated the correct value - which was known at the time - he'd probably never have gone, since he never could have survived such a long journey across the (apparently) open sea. So one may claim that Columbus was derided by experts but for perfectly sensible reasons - indeed, he never did reach India. No-one could possibly have known that America would get in the way and ruin the trip.

2) Bruno

We've met Bruno before and seen how his case has been twisted to fit an anti-religion agenda, whereas in fact things are much more complicated. At best, he appears to be an extremely rare case of a victim of an anti-science attitude among the Church. In all probability - there's some controversy over what he was actually burned for - it's far more likely that he was burned for a combination of a very bad attitude, plagiarising, and preaching unrelated religious heresies. In any case, he had absolutely no evidence for many of his beliefs, and though some of them did turn out to be correct, he was essentially little more than a mystic and a charlatan - hardly a martyr for science !

As I've said before, it's fine to use a magic pixie to give you ideas, but if your pixie doesn't tell you empirical ways to test those ideas, you need a better scientific advisor. More to the point, if your magic pixie tells you something that turns out to be correct, that does not necessarily vindicate your pixie's supernatural scientific techniques or even prove the existence of your supposed fairy godscientist. You can have ideas for whatever reason you like, but you have to test them in an objective, measurable, repeatable way. Bruno did nothing of the sort - right or wrong, he was still a crazy.

Obviously burning Bruno was a step that was a teensy-weensy bit too far, but if his ideas hadn't been dismissed, we'd also have to put up with people going on about planets made of shrubs and Nazi flying saucers living inside the hollow Sun... oh, God. I just made the fatal mistake of Googling that in case it was a genuine crackpot theory, and it is.

3) The Wright Brothers

This is rather outside my specialist area but it's very difficult to believe that they were "ridiculed and condemned for believing a machine could fly". In 1903 human flight had been a reality for at least 120 years since the Montgolfier brothers launched a balloon; there are reports of the Chinese using kites to lift people in the sixth century A.D. As for machines, the first steerable airships are reported from the late 18th century, while the first engine-powered airship took flight in 1852. Zepplins were already a thing by the time the Wright brothers were flying, and even the powered aeroplane didn't just come out of nowhere - experiments had been underway for many decades (and gliders for even longer). So the idea that the Wright brothers would have been ridiculed merely for proposing that a machine could fly is itself ridiculous. Yeah, I know, it's a meme, and memes are simplifications. But it's still wrong.

On the other hand, one can see why there might be rather more skepticism regarding the idea that heavier-than-air flight was the future, or that Wright's specific machine was such a wonderful revolution. Their first machines were extremely crude, it was not easy to envisage them being scaled up to anything resembling modern jet airliners. Certainly other experimenters were derided in the popular press due to catastrophic failures, yet even the then-famous Samuel Langely had managed to procure substantial government funding for his efforts. While it's true that the still-famous Lord Kelvin was very skeptical about flying machines*, a widespread opinion among experts that this was impossible looks rather unlikely.

* However I cannot find any reliable confirmation that he really said, "heavier than air flight is impossible", as is often quoted. That would have meant he denied the existence of birds, which is stupid. What he actually said was (somewhat) more moderate, albeit still strongly skeptical.

About the closest thing I can find to this is a quote from Scientific American, which is remarkably similar to a ClickHole article :

Interestingly, there appear to be strongly conflicting reports as to how much publicity the Wrights generated and wanted. Forbes has it that they were publicity-shy, yet newspaper reports don't necessarily back this up; others have it that the press were skeptical about the possibility of powered heavier-than-air flight (though this didn't last long). The general opinion seems to be that they wanted to keep things under wrap until they had a solid financial plan, which ironically meant a lack of publicity that could have generated business interest.“If such sensational and tremendously important experiments are being conducted in a not very remote part of the country, on a subject in which almost everybody feels the most profound interest, is it possible to believe that the enterprising American reporter…would not have ascertained all about them and published…long ago?”

So although there might have been an element of media denial, it doesn't look like that was borne out in the opinion of mainstream experts. I couldn't find any evidence of the Wright brothers being ridiculed by aeronautical experts, and even if they were, that could easily be attributed to them being overly-secretive - and it was, of course, dramatically and totally overturned in the space of a few short years. And if you Google, "Wright brothers ridiculed", you find results dominated by pseudoscience and related posts : "they were ridiculed" appears to be something people say to justify their silly theories, not something that actually happened.

4) Vesalius

I know even less about this dude than the Wright brothers, so this is limited to purely internet-based fact checking. Vesalius was a 16th century anatomist who was among the first to re-check the claims of the Greek physician Galen, who, it's fair to say, was treated quite wrongly as an authority beyond question. Certainly dogmatic thinking is a very real thing, of which the near-veneration of Galen is akin to that of Aristotle or Ptolemy. But what happened when Vesalius dared challenge the thousand-year gospel of Galen ?

It seems that reactions were somewhat mixed. He did suffer attacks for some of his discoveries, but I could find only one source claiming that he was denounced as a "heretic and imposter" (an odd choice of word - who was he impersonating ?), which is a self-confessed unorthodox book claiming that there's a very simple cure for cancer. The author also denies HIV is a disease and that chemtrails are actually a thing, for god's sake. Similarly, this very clearly biased website implies that the Church was very strongly opposed to dissections and that Vesalius went on a pilgrimage to avoid the Inquisition, which is now refuted by most scholars.

More reliable sources note that while he was subject to some vicious, personal individual attacks for taking on Galen ("the insolent and ignorant slanderer who… treacherously attacked his teachers with violent mendacity and time and time again distorted the truth of nature"), unauthorised copies of his books became available extremely quickly - hardly a sign of ridicule !

So my naive verdict would be that this is again largely a myth. You can always find someone to ridicule anything, just like you always can find anyone to agree with anything. There seems to be little or no evidence that Vesalius suffered anything like widespread ridicule or accusations of heresy, though it's worth noting that dogmatic thinking was definitely occurring even so.

5) Harvey

Another web-based fact checking exercise. At last, this one appears to have a grain of truth in it. Harvey was a highly respected physician who attended to no less than two kings , but he did lose some support due to his findings on blood circulation. Exactly how much is difficult to say, but it seems something of a stretch to say he was "disgraced" as a physician. He never lost his head or even his job, and though support for his findings was mixed (being rather more popular in his native England), he seems to have gradually won more converts within his own lifetime. Even so, he was not happy with the treatment he received from some of his detractors :

"You know full well what a storm my former lucubrations raised. Much better is it oftentimes to grow wise at home and in private, than by publishing what you have amassed with infinite labour, to stir up tempests that may rob you of peace and quiet for the rest of your days."So it seems fair to say that Harvey was discredited by some experts, but it's very hard to say if this was the majority viewpoint or not. Could it have been a vocal minority that were hounding him ? Possibly. It would take a proper historian to answer this one, but it seems to me unlikely that he was widely regarded as a crank.

6) Galileo

Galileo did not shy away from courting controversy on other issues besides the more famous heliocentrism (read that link for a full description of how and why it became as controversial as it did - Galileo himself is probably partially to blame*). But was he widely dismissed as a crackpot ? There seems to be little evidence of that, though undoubtedly his ideas on heliocentrism were controversial. A perhaps appropriate modern analogy might be Fred Hoyle, who more or less everyone acknowledges as a great scientist despite being wrong about a lot of things. Galileo was right, but he didn't really have the evidence to convince everyone - though again, there certainly was an element of dogmatic religious thinking going on here.

* Galileo was a brilliant but complex man. Reportedly he liked engaging in "robust conversations" with anyone who disagreed with him, Church or no. For example although he corresponded with Kepler, he apparently mocked his (correct) idea about the Moon being responsible for tides, and just never responded when Kepler suggested that planetary orbits might be elliptical. On the other hand, this didn't stop him from recommending Kepler for a mathematics position ! This attitude, as I can attest from first-hand experience, is not so uncommon today - some professors only respect you once you start to fight back.

As far as the meme goes, Galileo was placed under house arrest, which is a bit different to being thrown in prison. Galileo didn't invent the idea of heliocentrism, nor were his predecessors even arrested for their ideas. So as to the direct implication of the meme that Galileo was arrested because heliocentrism was not tolerated - well it's just not that simple.

7) Everything That Can Be Invented...

Not exactly a case of an individual having a crazy-but-true theory, but still a classic example of scientific hubris. This popular quoteable quote does seem to be an urban legend - apparently originating not from a patent commissioner, but a joke in an 1899 issue of Punch magazine. But what of the other widely-reported idea that scientists near the end of the 19th century thought they'd basically got everything licked ?

There may be some truth to this. Wikipedia states that, in the last years of the 19th century, no-one would have believed that physics was not all it was cracked up to be :

So profound were these and other developments that it was generally accepted that all the important laws of physics had been discovered and that, henceforth, research would be concerned with clearing up minor problems and particularly with improvements of method and measurement.But was it really generally accepted ? Harder to say. This discussion thread gives arguments for and against; certainly there were examples of deep hubris, but the general mood is something much less easy to determine. Let's assume that really was the case. It didn't last very long - the few short years at the start of the 20th century saw long-held ideas saw an undisputed scientific revolution. Despite the magnitude and outlandish nature of his claims, few seem to have regarded Einstein as a crank. Controversial, sure - but that's not the same as dismissing someone as a crackpot, and it was hardly as though the scientific establishment wasn't prepared for new ideas.

8) Invention of Lasers

I described the maser and its performance. "But that is not possible," he [Bohr] exclaimed. I assured him it was... After I told him [von Neumann] about the maser and the purity of its frequency, he declared, "that can't be right !" But it was, I replied, and I told him it was already demonstrated... A younger physicist in the department, even after the first successful operation of the device, bet me a bottle of scotch that it was not doing what we said (he paid up).So a bit of a grilling from some experts. But by no means all.

Engineers... never had a hard time with the precise frequency the maser produced. They accepted as a matter of course that a maser oscillator might do what it did... Rabi and Kusch, themselves in a similar field, for this reason accepted the basic physics readily. But for some others, it was startling.And at least some of the doubters - and let's please also bear in mind that the inventors were able to publish papers and secure funding for their experiments - changed their minds very quickly when the physics was properly explained to them :

I am not sure I ever did convince Bohr... After I persisted, he said, "Oh, well, yes, maybe you are right," but my impression was that he was simply trying to be polite to a younger physicist. Von Neumann... wandered off and had another drink. In about 15 minutes he was back. "Yes, you're right," he snapped. Clearly, he had seen the point.So, widespread dismissal ? Hell no. Not a bit of it. It's true that they had some brief problems getting the paper published - but that seems to be only because they tried for a prestigious journal which had just published a supposedly similar paper (very prominent journals try to focus on novel ideas). Dismissed as cranks ? Laughed at ? Ridiculed ? Not in the slightest.

9) Radio Waves From Spaaaaaace !

Ummm.... no ? Plenty of scientists were expecting to find radio waves from space decades before this actually happened, though the precise apparatus required wasn't properly understood. However, it's true that the discovery of the ionosphere discouraged efforts, as it blocks long-wavelength radiation. It's also true that the eventual detection was serendipitous and didn't exactly have people dancing in the streets. Jansky himself did no further research* into radio astronomy, but the first dedicated radio telescope was built just a few years later. Even WWII didn't stop research completely, though things didn't really pick up until the 1950s.

* Jansky was working for a private company and there wasn't any obvious commercial application of his discovery. Things would almost certainly had been different if he'd been working at a university.

I can't find any evidence that anyone trying to start doing radio astronomy was ever ridiculed. I suppose it could be argued that people stopped looking for radio waves after the discovery of the ionosphere, but a) that's a bit different from calling people names and b) it could also have just been due to the technological limitations of the time (detecting emission at different wavelengths can require radically different instruments). At most, you could make a plausible argument that it took a while until the importance of radio astronomy was widely accepted.

10) Magnetic Fields in Galaxies

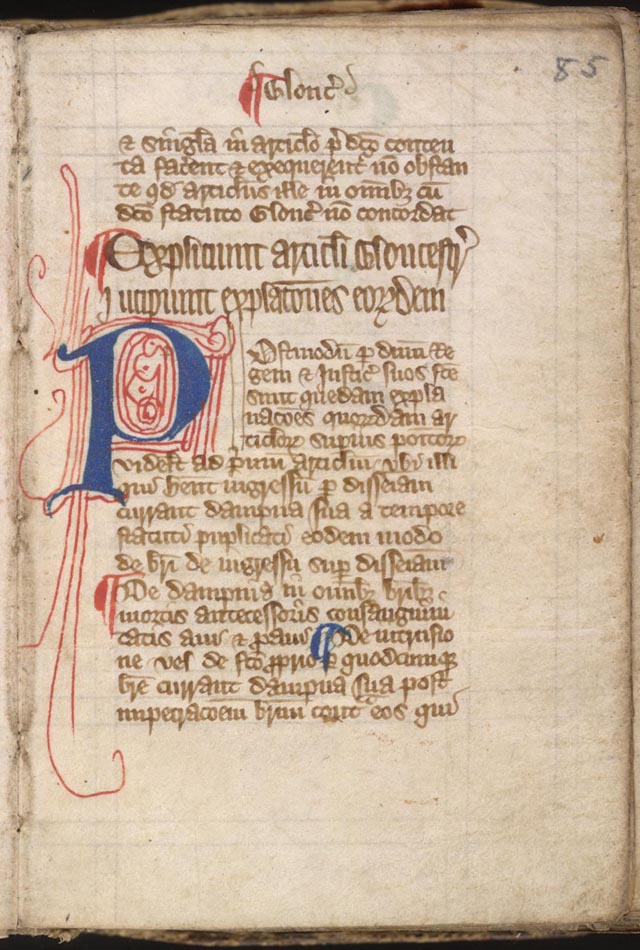

| The magnetic field in our own Galaxy. |

I don't particularly want to go in to that. It's possibly something - eventually - for a future post, but right now we need to cut to the chase. The problem is that the discovery of a galactic-wide magnetic field was predicted by Hannes Alfvén in 1937, who is basically idolised by the EU community in much the same way that Tesla and Zwicky are sometimes worshipped by their fanboys elsewhere on the internet. This means that researching this comes up with all manner of websites bluntly stating things that just aren't true or can't be verified, e.g. that Alfvén predicted the filamentary structure of the Universe in 1963 (there's no record of this on ADS), that for some reason this "confounded" (well at least it's not "baffled"....) astrophysicists in 1991 (it was actually known by the early 1980's), that this "added to the woes of Big Bang cosmology" (it does nothing of the bloody sort !), or that mainstream astronomers think that black holes cause galaxies to spin - which we just don't, because that's stupid.

The only thing I can reliably determine here is that Alfvén was indeed a controversial figure. He won scholarships, professorships, and ultimately the Nobel prize - hardly the sign of being regarded as a crackpot - yet apparently he had difficulty publishing papers. Certainly his proposed alternative cosmology is derided as mad, because it is. Similarly, Halton Arp was both widely respected for his Atlas of Peculiar Galaxies but condemned for his bizarre ideas about redshift. But did Alfvén face ridicule specifically for proposing that galaxies have magnetic fields ? About the only thing I can find is that it was "generally disregarded" and, shamefully, when the fields were discovered his original proposal wasn't acknowledged. Alas, getting to the bottom of this requires a true science historian and a genuine expert in plasma physics.

11) You Will Not Go To Space Today

Rockets have been in use for more than 700 years, but it wasn't until the 20th century that they received any amount of serious theoretical and practical attention from scientists. American rocket pioneer Robert Goddard was, if not ridiculed by the establishment, certainly not taken entirely seriously and was indeed lambasted in the press. The problem, perhaps, was that for the bulk of their already long history, rockets had been pretty crappy - powerful and terrifying, but wildly inaccurate. Using them to travel anywhere must have seemed like trying to ride a tiger.

Goddard seems to have been able but reluctant to publish, at least in part due to trepidation about how this would be received by the scientific community. However, the media attacks were vicious and unjustified, famously (and totally erroneously) claiming that rockets can't work in space*. No scientist would ever have said such nonsense (Goddard published rebuttals in scientific journals), though there are plenty of idiots still claiming such tripe today, but dealing with a hostile media appears to have sent Goddard into hiding. Things did change in his lifetime, but slowly. It perhaps didn't help matters that one of the other great pioneers of American rocketry was an out-and-out fruitcake.

* Even worse was their assertion of Einstein and colleagues as a scientific elite authority - urrrgh !

Unfortunately, while it's trivial to find out what the ignorant press were saying, it's nigh-on impossible to find out what scientists were saying. Many articles mention criticism from other scientists, but actual quotes appear to be non-existent. Clearly the responses must have been mixed, because he was publishing papers and securing patents and funding (albeit at a modest level). Goddard appears to have been naturally shy, but dealing with criticism is fundamental to the scientific method - given the track record of rockets at that point, harsh criticism might well be expected.

Goddard produced a memorable quote to a reporter :

Every vision is a joke until the first man accomplishes it; once realised, it becomes commonplace.While true, thus far it's not seeming very likely that every good idea seems like a joke to the expert community, although Goddard would surely have approved of the Ig Nobel Prizes. But however strong the criticism in the US, elsewhere in the world Goddard and his rockets were being taken very seriously indeed.

12) Death From Above

That rocks from space occasionally collide with the Earth is now such an absolute certainty that it's almost difficult to believe that at one point, the scientific establishment was having none of it. The problem is that impacts are so rare that it's incredibly unlikely a scientist would just happen to be in the right place at just the right time to witness such an event. Terrestrial meteor craters are not always easy to spot or to distinguish from volcanic craters, similarly volcanoes were invoked to explain lunar craters (never mind the bizarre alternative pseudoscientific theory of "world ice"). Meteor showers were once explained as being the results of volcanic explosions or even an atmospheric phenomena, until eventually a meteorite impact had such a large number of witnesses that it couldn't be discounted.

It's worth remembering that at the time, the existence of the asteroid belt was utterly unknown. Theories of the formation of the Solar System were still in their infancy (perhaps they still are); no-one could reliably predict the existence of countless small rocks floating around in space. In contrast, volcanoes were definitely a known thing, as was lightning. So a terrestrial/atmospheric origin was much more likely given the evidence at the time. Thomas Jefferson even said that he'd rather believe that a professor would lie than the idea that "stones would fall from heaven".

There doesn't seem to have been a single leading figure in the early days of the extraterrestrial meteor hypothesis - it was a slow, gradual accumulation of evidence. Although there were those who ridiculed the idea, overall, it seems to have been little more than ordinary, entirely legitimate skepticism. Widespread ridicule, once again, does not seem to have been much of a thing, and in the worst case it quickly faded as the evidence mounted.

13) The Big Bang

Oh, delicious irony. Pseudoscientists today just love to try and debunk the Big Bang, claiming (as mainstream scientists had once done) that it's nothing more than stealth Creationism. Yet it took many decades before the Big Bang was established as the mainstream viewpoint, and during that time things did indeed get ugly - with Fred Hoyle famously coining the very term, "Big Bang" as a pithy way to dismiss it*. Nowadays the Steady State theory belongs firmly in the realm of pseudoscience, though an unsteady state model might be feasible if you have an inexplicable desperation to avoid a "creation" event.

* He also said, "The reason why scientists like the "big bang" is because they are overshadowed by the Book of Genesis. It is deep within the psyche of most scientists to believe in the first page of Genesis", while simultaneously advocating something approaching the strong anthropic principle. It's fair to say that his views on science and religion were anything but simple.

So indeed the worm has decisively turned on this one. But was mainstream science being overly-dismissive of the idea ? Initially, probably not - if the only evidence was galaxy redshifts, it made sense to consider other options. But as the evidence gathered (an unavoidably slow process), the theory won more converts. There was certainly a strong element of prominent, public denial and even ridicule - but any argument that the main community had a persistent adherence to the older order doesn't stand up. Moreover, the instigator of the idea - Georges Lemaître - was on speaking terms with Einstein and Eddington, so the reception was very much "mixed", with not much hint of any one-sided derision of crackpottery.

14) Wegener

Alfred Wegener is someone I've long proposed should have a law akin to the more famous Godwin's Law - just as anyone mentioning Hitler instantly loses the argument, so should anyone comparing their theory to Wegener's ideas on continental drift. It's true that he was vindicated long after his death after being almost completely dismissed during his lifetime. It's also true that, although not a geologist, he presented a good deal of evidence in support of his theory.

Wegener appears to have been misunderstood for a variety of reasons. On the more positive side, he didn't speak good English so didn't defend his theory when aspects of it were misunderstood. He also didn't produce a satisfactory mechanism to explain it (though he did speculate along very promising lines), which for an idea this radical was a huge disadvantage. And other explanations seemed largely able to deal with the known problems without recourse to such a novel idea. The more negative aspect is that Wegener wasn't a geologist, and scientists don't always appreciate experts in other fields (i.e. non-experts) contradicting their ideas. The problem is that there's a very good reason for that : the non-experts are usually wrong !

Wegener, like Hitler, is an extreme case - it doesn't make a lot of sense to compare fringe ideas to Wegener any more than you should compare the EU to Nazi Germany. It's true that unlike Bruno, he had good evidence for his ideas - but he still had little clue about the mechanism. And while he was mocked for continental drift, it doesn't seem to have done his main career (as a polar researcher) much harm. Which is not so uncommon as you might think.

Conclusions

Scientific credibility, like most things, is a spectrum - ranging from mathematical certainties to absolute drivel. There isn't always a clear line between mainstream science, fringe ideas, and abject pseudoscience - but it's usually possible to differentiate between promising ideas and really stupid ones. By and large, ideas which have been extensively labelled by experts for prolonged periods as mad have tended to actually be mad.

Of course, science is a human endeavour subject to all the usual flaws, despite the many safeguards in place to minimise them. Yet in general, if you have to resort to saying, "I'll be vindicated one day !" then you've basically admitted you don't have enough evidence to support your claim. True, occasionally such claims are borne out - but the road of scientific progress is littered the corpses of far more such ideas that were simply wrong. Saying, "the establishment got it wrong once" in absolutely no way whatsoever implies that your terrible idea is somehow actually a good idea.

It's all very well to point out that the public and the media have unleashed scathing criticism on some ideas - that's pretty common, you're on very firm ground with that one. And not all that unexpected either, since the lay public are by definition not as qualified as experts. It's also useful to remember not to pay too much attention to the slings and arrows, because reality doesn't care what people think of it.

But if you want to claim that all the experts just aren't listening, the popular historical examples suggest that you're on very thin ice indeed. Many of these appear not to have happened at all - the experts never dismissed Columbus or the Wright brothers. Others are more complicated - some experts did react strongly, only to retract their objections later (in some cases in a matter of minutes), while often there's a strong element of the historian's fallacy at work : often the evidence just wasn't good enough, and the dismissal was nothing more than standard skeptical inquiry without which science would never get anywhere.

It's really, really hard to find any clear examples of widespread, prolonged expert dismissal that flies in the face of the evidence. Certainly individuals are wholly capable of this (Fred Hoyle being the classic example), while widespread prolonged dismissal by the press happens quite often (e.g. Robert Goddard, climate change). Wegener probably comes closest to this, but even he didn't really have a good mechanism to explain continental drift, so it's not quite the same as if the evidence was being ignored. As for Alfvén, that's a possibility - the problem is that since his sainthood by the Electric Universe lot, it's damned hard to find anything about him that isn't unequivocally biased. Possibly, like Wegener, he never made a determined effort to convince his detractors, or possibly his good ideas were drowned out by his unnecessarily radical alternative cosmology.

I hate this quote. The thing about skepticism is that you have to fight back. That's part of the point : to provoke debate, not suppress it. If, like Goddard and Wegener, you don't really try, no-one's ever going to believe you. Which is an unfortunate reality for those not prepared to fight their corner. You can have an idea as crazy as you like, but if you don't have evidence to support it and you don't try to defend it, there's no reason to expect people to believe it. If people dismiss you and you still believe it, keep trying to get new evidence. But if absolutely everyone is still against you, perhaps you're, well, just wrong ?

Pseudoscientists love to play the, "they laughed at all these guys" card. As we've seen, that's an over-simplification at best, and at worst it's just not true. It's also an admission of weak evidence, which means there's little reason to prefer their ideas to any others. Of course all new ideas are treated with skepticism and are often controversial, but that's trivial and hardly worth mentioning. But, as far as I can tell, the evidence for systematic, widespread expert denial appears to be very thin indeed. Even when dogmatic thinking was occurring, such as with the veneration of Galen and Aristotle*, once evidence began to be presented, opinions changed.

* It's very unlikely that such authority figures could dominate science again. Most genuine experts are well aware that even the leading names in their fields make mistakes, because it wouldn't be research if you knew what they were doing. Some people carry more weight than others, but no-one is beyond question. However for other ways in which freedom of thought can be stifled in modern academia, see this.

Still, I want to end on a a couple of caveats. First, a few months ago I came across an article which looked to be the Platonic ideal for the pseudoscientists : claims that mainstream academia had not only dismissed ideas of animal consciousness/intelligence for many years, but also dismissed researchers from their posts for going against the mainstream. It appeared to be well-cited and with numerous examples. Despite a great deal of searching I've been unable to find it again. If anyone out there has any idea which article I'm talking about, do get in touch.

Even with these caveats I'm surprised at the strength of this result, the possible animal intelligence article notwithstanding. Although strongly-worded debates are part and parcel of changing the consensus, still, I expected to find at least a few cases where the bulk of the establishment had persistently ignored or condemned strong evidence - conservative thinking is an entirely natural human tendency. Yet there appears to be not a single case of someone initially seen as a crank who presented good evidence still being widely treated as a crank, even in the Middle Ages when science, faith and mysticism were intimately connected. Curiosity, open-mindedness, and a simple desire to learn are not so easy to suppress, nor, though it undoubtedly does happen, do either religious or scientific institutions inevitably act to enforce dogma. Maybe there's hope for us yet.