Here is the latest batch of questions and answers for your reading pleasure.

I really should have thought of some better innuendos considering this is the XXXth post in the series. Ah well.

1) What do you think about this article about Dragonfly 44 being mostly made of dark matter ?

I've read some excellent articles in Scientific American but this isn't one of them.

2) How can the Universe be expanding if it's infinite ?

It isn't infinite, that's a silly idea.

3) Could Dragonfly 44 be full of Dyson spheres and that's why it's so faint ?

Yes, that's definitely the answer. You've solved it. Well done. Slow clap.

4) Are you very skeptical about Dragonfly 44 ?

Meh.

5) How do we know if a black hole is spinning ?

Measurements.

6) Yes, but tell us how you really feel about Dragonfly 44.

Sigh.

7) Why is a star's gravity stronger after it dies ?

Physics.

Follow the reluctant adventures in the life of a Welsh astrophysicist sent around the world for some reason, wherein I photograph potatoes and destroy galaxies in the name of science. And don't forget about my website, www.rhysy.net

Sunday, 28 August 2016

Saturday, 27 August 2016

My Dark Galaxy Is Darker Than Your Dark Galaxy

|

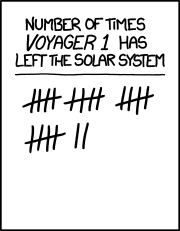

| From xkcd : So far Voyager 1 has 'left the Solar System' by passing through the termination shock three times, the heliopause twice, and once each through the heliosheath, heliosphere, heliodrome, auroral discontinuity, Heaviside layer, trans-Neptunian panic zone, magnetogap, US Census Bureau Solar System statistical boundary, Kuiper gauntlet, Oort void, and crystal sphere holding the fixed stars |

A galaxy called Dragonfly 44 is currently having its 15 minutes of fame in the media, sometimes described as a "new class of galaxy". It seems to have about the same mass as the Milky Way but a hundred times fewer stars. And don't get me wrong, it's a very interesting object indeed, and it's good thing it's getting so much press coverage. But while it may be helpful to sell this as the "first" such detection, in reality things are a bit more complicated than that. So without further ado, let's look at a short selection* of other really dark galaxies, some of them much more extreme than Dragonfly 44.

* This is by no means a complete list. For a reasonable attempt at a complete catalogue, see my recent paper, especially appendix B. I also already covered the Smith Cloud in some detail here and Keenan's Ring here .

1) HI1225+01

Sometimes known as the Giovanelli & Haynes cloud, after its discovers. This was detected way back in 1989 by sheer luck in an Arecibo survey, and was billed as the possible first detection of a "protogalaxy". The cloud is a bloody enormous band hydrogen around 650,000 light years across with the mass of around 4 billion suns. And it seemed to be rotating, too quickly to be held together by the mass of the gas alone. Like nearly all galaxies, it would need some unknown "dark matter" to keep it from flying apart.

Then things got complicated.

See that fuzzy blue patch near the top of the hydrogen ? That's a dwarf galaxy that was spotted soon after the gas was detected. So part of the cloud contains a more-or-less normal galaxy. Could the rest of the gas just be some sort of "tidal" feature of the gas, pulled out of the dwarf galaxy by the gravity of some other passing galaxy ? Unlikely. First, there's nothing else nearby that could have done this, and second, a galaxy as small as the dwarf shouldn't have anything like this much gas.

So while HI1225+01 is one of the first discoveries in this list, no-one really knows what it's a discovery of. We don't know for sure if the cloud is rotating or not. Some people think the southern part of the cloud could still be a dark galaxy in its own right. But no-one really knows.

2) Malin 1

| From Bad Astronomy, with another artist's impression of the Milky Way shown for scale. |

Overall, it's probably about as bright as normal spirals, but its area is around 100 times larger. In contrast, the gas density is about normal - it's only got a lot of gas because it's so bloody big. Which is weird, because gas density is normally a good measure of star formation. What's going on ? No-one knows. You couldn't call Malin 1 a dark galaxy, but it's obviously a very dim one and it's certainly an extremely strange object.

3) HIJASS J1021+ 6842 (great name, guys)

Those early discoveries of the 1980's were somewhat lucky. Few other dark or weirdly dim galaxy candidates turn up until the early 2000's, when new instruments made it possible to map the hydrogen sky as never before. These early surveys had very poor resolution and sensitivity compared to today's standards, but they did reveal a few weird objects. One such object turned up in the M81 galaxy group.

|

| Image from sky-map.org. |

|

| Image from helixgate.net. |

|

| Left : low resolution image from the discovery paper, showing the cloud connected to the (much brighter) IC 2754. Right : higher resolution image of the cloud itself, from a follow-up paper from 2005. |

4) GEMS_N3783_2

|

| From a 2006 paper. |

* And also, looking for hydrogen in this way is still a difficult, slow process. It will be many years - if not decades - before we're mapped the whole sky in this way.

It's not clear. I would say, "probably", but the original authors say, "probably not." There are a few other galaxies a bit closer, but they don't seem to be particularly disturbed, and the mass of gas in the cloud is rather large. Personally I don't think a tidal origin is very likely for this object. The authors main reason to reject this as a dark galaxy is that very few dark galaxy candidates are known... much fewer than models predict. But this is a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy !

In my opinion this is an under-rated dark galaxy candidate. The really intriguing thing is its velocity width (which can indicate rotation), which is a very respectable 100 km/s. As I've shown in great, great detail, it's really frickin' hard to form tidal debris with properties like this. A more reasonable objection is that the optical data of this region isn't very sensitive - so there could be a faint galaxy there after all, hiding in the noise of the image. Still, that would be not dissimilar to Dragonfly 44, 10 years before that discovery.

5) GRB060505comp

|

| From the 2015 discovery paper. The red contours show the gas. 19 kiloparsecs is about 62,000 light years. The grey ellipse shows the size of the telescope beam on the sky. |

But the authors of the paper don't think so. The closest they get is to note that given the sensitivity of the optical data, if this object does have any visible light at all it would be incredibly faint - thousands of times fainter than the Milky Way (or more) despite having about the same amount of gas. They favour that it's an infalling gas cloud, which isn't very helpful. Where has this cloud come from, and why do so few galaxies have associated clouds this massive ?

6) VIRGOHI21

Although I've covered VIRGOHI21 before (see also Robert Minchin's blog post) it's worth re-iterating because this still dominates search results for "first dark galaxy". It's a blob of hydrogen a bit smaller than the Milky Way but with perhaps a hundred times less gas, and no detectable stars whatsoever - despite incredibly sensitive observations with Hubble. If it's rotating it would be made up of at least 99.8% dark matter, with an extremely high line width of 200 km/s.

Long story short, again we don't know if the structure is really rotating or not. So is it a massive dark object which pulled that stream of hydrogen out of the spiral galaxy, or is it just tidal debris, with some other object pulling out the stream and causing the illusion of rotation ? We really don't know. Being inside a whole cluster of galaxies - not just a small group - this is a particularly complicated simulation. Based on the latest simulations (which I hope to publish later this year) I'd have a hard time picking the most likely explanation.

7) Crater 2

No pretty picture for this one because it was discovered by counting stars - it's so faint you can't even see it in the image if you know it's there. Which isn't all that unusual. Crater 2 is remarkable for its size in the Local Group (our patch of turf in the Universe), but we don't know how dark matter dominated it is yet.

8) The AGES Clouds

I've described these before in detail because they're my own research. Short summary : they're eight clouds of hydrogen of a few tens of millions of solar masses, with line widths of up to 180 km/s, floating around in the Virgo cluster. They're at least 300,000 light years from the nearest galaxy and (at most) the same size of the Milky Way (though they could also be smaller). We don't have a good explanation for these objects, but we're pretty confident they can't be tidal debris. Like most of these other candidates, they'd need more than 99% of their mass to be dark matter if they're really rotating as the measurements suggest they are.

9) VCC 1287

Now just to sow some extra confusion into the idea of which dark/dim galaxy candidate was the first, consider this pathetic smudge of starlight. VCC 1287 has been known since at least 1985, earlier than Malin 1 or HI1225+01 - but it was only earlier this year that its internal motions were measured. That found that it had far more dark matter than a typical galaxy of this size or brightness, being at least 99% dark matter but plausibly more like 99.99% (a more typical value might be 90%). It's quite a bit smaller than the Milky Way, having a diameter only about 15% as large. Unlike some of the other candidates it doesn't seem to have any gas at all.

This galaxy and the AGES clouds are all in the Virgo cluster, and all appear to have far more dark matter than expected given their mass of ordinary matter. Could there be a connection ? Could the gas-rich clouds have all their gas transformed into stars and become things like VCC 1287 ? Perhaps. The gas mass in the AGES clouds matches the stellar mass of VCC 1287 pretty well, as does the estimated dark matter mass in each system.

10) Like, all these hundreds of other objects

|

| From the press release about 800 ultra-diffuse galaxies in the Coma Cluster. |

So far these new discoveries have been in clusters. They can be as large as the Milky Way but a thousand times fainter. It's difficult to know how dark matter dominated they are - we need to measure their internal motions to properly estimate how much dark matter they contain, and that's very difficult because they're so faint. But given that they'd apparently survived inside a cluster without being torn apart, estimates said they've be made of at least 99% dark matter. And that's what Dragonfly 44 appears to be confirming.

Conclusions

So is Dragonfly 44 really the first of a new class of galaxy ? Not really. Various sorts of incredibly dim galaxies have been known for many years. Some might be purely gas and dark matter with no stars at all, others appear to have no gas in whatsoever, while a very few are very gas rich but have just a few stars too. Many of the pure gas candidates remain controversial - people seem to have this odd bias against believing that gas clouds can endure without forming any stars. Chuck in even just a few stars and it's, "ooooh, look at that faint galaxy"; without them they're all like, "that's just tidal debris". I'm not really sure why.

It's very hard to justify some of the statements in the Dragonfly 44 press release, even (especially) given the need for simplifications. It certainly isn't the first time a galaxy has been detected that needs dark matter to hold it together, because that's true of all galaxies ! Nor is it the first time a galaxy has been shown to have an unusually high dark matter content from its stars rather than gas, as VCC 1287 demonstrates. It's also not the first time the prospect of a really massive dim or dark galaxy has been raised, as we've seen.

But you might be wondering that maybe this is the first time something like this has been directly measured, and that's what all the fuss is about. Well, maybe - but it's far from clear that's the case. Never mind the press releases, in the original paper the authors say :

...in our study the total halo mass is an extrapolation of the measured mass by a factor of ∼ 100. A more robust and less model-dependent conclusion is that the dark matter mass within r = 4.6 kpc is similar to the dark matter mass of the Milky Way within the same radius.So is this galaxy massive or not ? We don't know. The problem is that we can directly measure (assuming our theory of gravity is correct) the mass only where we have something to measure the motion, i.e. stars. But we don't know how much further the dark matter extends - the only way to measure that would be through gravitational lensing, which is tricky to do. Currently the total mass estimate is based on the results of numerical simulations, so I would treat the result with some caution. And for those very few other "ultra diffuse" galaxies for which a mass estimate is possible, it seems that most of them are dwarves rather than giants*.

* Also, one oddity struck me while comparing the VCC 1287 and Dragonfly 44 papers. In the VCC 1287 paper, the authors say they can use the total number of observed globular clusters to estimate the total mass. In the the Dragonfly 44 paper they use the same trick, but seem to think it only tells them about the enclosed mass at that radius - which is very much lower than their highest mass estimate. It's not clear to me what's going on here.

Let's assume that the high mass estimates are correct though. How important would this be ? Well, from the Dragonfly 44 article in the Washington Post :

On the one hand yes, on the other no. I'd have said that there were more than enough problems with galaxy formation theory to give anyone pause for thought, as the above examples should illustrate. Does Dragonfly 44 change this ? Sort of, maybe. It was already clear that we don't really understand how the gas gets turned into stars very well at all, as we've seen in several examples. Dragonfly 44 takes things further : now it seems we don't understand how normal matter gets into dark matter halos in the first place too."We thought that that ratio of matter to dark matter was something we understood. We thought the formation of stars was kind of related to how much dark matter there is, and Dragonfly 44 kind of turns that idea on its head," he continued."It means we don’t understand, kind of fundamentally, how galaxy formation works."

But... we knew that already ! As I've written about a great many times previously, observations don't show anything like as many galaxy as models predict. What Dragonfly 44 does mean though, possibly, is that the nature of the problem is worse than we thought. Significantly so.

The thing is, if these new discoveries are all dwarves, that doesn't solve the missing galaxy problem because they're aren't nearly enough of them. But it opens the door to a solution : if so many dwarves form just a few stars, maybe lots more form none at all. Yay ! We also know that some of the missing galaxies are so big there's no way they should be able to avoid forming stars. The D44 mass, if correct, would mean that at least some of them do form a very few stars. But why ? Why should some objects form a thousand times more stars than others despite having the same total mass and being in the same environment ? And worse... are there giant dark matter halos out there without any stars at all ?

That's the point. Dark galaxies were thought to be a way to solve the missing galaxy problem, but then that was only thought to apply to the smallest objects - and later, a few which were a bit bigger. There wasn't ever a problem of missing galaxies as large as the Milky Way - although there were clearly problems with star formation, at least the number of galaxies observed was roughly in line with the simulations. But now D44 indicates there might be a problem where we never knew there was one. Maybe there are now large numbers of massive galaxies out there our models didn't predict at all. If that's really the case, it could be very scary and exciting all at once.

Sunday, 21 August 2016

Ask An Astronomer Anything At All About Astronomy (XXIX)

Endless questions ! Surely by now we've covered everything ? No ? Fine...

1) Could Sagittarius A* be a white hole ?

Hah ! No chance. Dream on, loser.

2) Could the Big Bang be a white hole ?

Yes, but it could also be a magical wizard.

3) Is the most spherical planet the one that's the most massive ?

That's right, it's yo momma.

4) Why didn't the light from the Big Bang pass us by as the Universe expanded ?

Because we smell terrible.

5) Is the "total energy of the Universe is zero" statement a bit of creative accounting ?

I'd say so.

6) If Andromeda were to go nova, how much would it affect the Milky Way ?

That's un-possible.

7) Why do you want physics to be broken ?

I dunno, why do you want your face to be broken ?

8) What's the truth behind Nibiru ?

IT'S ALL TRUE ! ALL OF IT ! EVEN THE PARTS THAT CONTRADICT THE OTHER PARTS ! WE IS ALL GONNA DIIIIIE !!!!

9) Could Venus not be having a super-greenhouse effect but just cooling down from some recent catastrophe ?

I dunno, but defining "recent" and "catastrophe" would help.

10) How can we improve communications to robotic spacecraft ?

By shouting more loudly from a taller hill.

Also I made a correction to one previous answer :

Q : If black holes and white holes have the same gravity, doesn't that mean they're the same thing ?

My original answer was that whites hole have anti-gravity. This is completely wrong. They're actually time-reversed black holes, apparently. The answer to the question is that no, they're not the same thing but only because general relativity is bloody complicated. I won't pretend to understand the details, so I'll be rather more careful with white hole questions in future.

Added some more information to another previous question :

Q : Could rogue stars be parts of mostly dark matter galaxies ?

It seems that some people think so. Personally I'm skeptical - it would be extremely hard to prove that these isolated stars are really embedded in dark matter halos since you can't measure a rotation curve for just a few stars. Which means the idea is very hard to disprove, and when you start allowing ideas that can't be disproven you're in very dangerous territory. I don't say it's impossible, but I'd need further convincing.

1) Could Sagittarius A* be a white hole ?

Hah ! No chance. Dream on, loser.

2) Could the Big Bang be a white hole ?

Yes, but it could also be a magical wizard.

3) Is the most spherical planet the one that's the most massive ?

That's right, it's yo momma.

4) Why didn't the light from the Big Bang pass us by as the Universe expanded ?

Because we smell terrible.

5) Is the "total energy of the Universe is zero" statement a bit of creative accounting ?

I'd say so.

6) If Andromeda were to go nova, how much would it affect the Milky Way ?

That's un-possible.

7) Why do you want physics to be broken ?

I dunno, why do you want your face to be broken ?

8) What's the truth behind Nibiru ?

IT'S ALL TRUE ! ALL OF IT ! EVEN THE PARTS THAT CONTRADICT THE OTHER PARTS ! WE IS ALL GONNA DIIIIIE !!!!

9) Could Venus not be having a super-greenhouse effect but just cooling down from some recent catastrophe ?

I dunno, but defining "recent" and "catastrophe" would help.

10) How can we improve communications to robotic spacecraft ?

By shouting more loudly from a taller hill.

Also I made a correction to one previous answer :

Q : If black holes and white holes have the same gravity, doesn't that mean they're the same thing ?

My original answer was that whites hole have anti-gravity. This is completely wrong. They're actually time-reversed black holes, apparently. The answer to the question is that no, they're not the same thing but only because general relativity is bloody complicated. I won't pretend to understand the details, so I'll be rather more careful with white hole questions in future.

Added some more information to another previous question :

Q : Could rogue stars be parts of mostly dark matter galaxies ?

It seems that some people think so. Personally I'm skeptical - it would be extremely hard to prove that these isolated stars are really embedded in dark matter halos since you can't measure a rotation curve for just a few stars. Which means the idea is very hard to disprove, and when you start allowing ideas that can't be disproven you're in very dangerous territory. I don't say it's impossible, but I'd need further convincing.

Sunday, 14 August 2016

Beowulf

Adaptations of the epic Anglo-Saxon tale of Beowulf are plentiful, possibly because few of them are any good. ITV's latest effluent entry isn't worth speaking of any further, but it did prompt me to complete a long-standing item on my to do list and read the original poem.

Well, I say original. Of course I can't read Old English so I went for a modern translation. However, my online searches seemed to find two versions : colloquial prose or truly archaic poetry that could only be called "modern English" because of the vocabulary. I want something in the middle. As a poem it simply does not work in modern English (scholar's opinions be damned) : line breaks appear entirely at random, and there's no rhythm to the sentences. But the language ! It's as beautiful as anything Shakespeare or Homer ever came up with.

I opted to take as light a touch as possible. It certainly won't please everyone, but that's not the point - I want something that I can read, and if anyone else enjoys it that's a bonus.

First, I removed those infuriating line breaks. I then had to create paragraphs because a wall of pure text is just awful. I also had to edit the punctuation, particularly commas. I don't know if it was the fault of the original poet, the translator, or both, but the original, poem has commas placed, more or, less at random, and far too often. I tried to do this only where I thought it absolutely necessary. Occasionally, I replaced some of the commas with hyphens to more correctly structure the sentence in prose form. Sometimes commas were replaced with "and" because it's just better that way. I also removed a lot of semicolons, as the original translation seems to have been written by someone who forgot they weren't writing Turbo Pascal.

The poet was wont to reverse the usual adjective-noun structure, so that a hardy warrior becomes a warrior hardy. Most of the time this is used to tremendous poetic effect. On a few occasions, however, I deemed it necessary to revert to the modern convention : an "atheling excellent" just doesn't make any sense in modern English. On even fewer occasions whole sentences sounded simply too much like Yoda-speak, and really quite ugly. The poet surely did not intend this, so very occasionally I edited the structure of whole sentences. This usually happens when the description of a character suddenly follows after what it is they've done (or even in the middle of a sentence describing what they're doing), which is distractingly confusing.

Words too I tried to preserve wherever possible, but I did make a few changes I found necessary (obviously, American spellings have been replaced with the correct British versions). Hrothgar cannot be called, "helmet of the Scyldings", because that sounds bloody daft : he's now their chieftain or king. One major change I did make was to replace "Geats" with "Weders", since I simply don't like the sound of, "Geats". It sounds too much like a goat-sheep hybrid. Historians probably won't be happy, but never mind.

A lesser replacement was to change "worm" to "wyrm" as I think the latter is more normally understood to refer to a dragon. "Beer hall" became "mead hall", again appealing the standard modern expectations of the Viking era. "Henchman" became various different words because it has far too many James Bond villainous connotations for modern use. "Recks" became "heeds" because the word works equally well and is more readily understood. "Gripe" usually became "grip" since the modern meaning is too different. "Hied" became "hurried". "Welkin" becomes either "sky" or "heaven". "Wyrd" became "fate" or "destiny". "Swan-road" became "whale-road" because it's found in alternative translations and sounds infinitely better. "Bale" usually becomes "bane", because bale is usually taken to mean a bale of hay (or a group of turtles, though that's not a very likely interpretation*). "Bairn" became "son" or "child", because bairn is no longer used outside Scotland. Wherever possible, replacement words were chosen to preserve the alliteration. And while I've mostly kept things like, "o'er", "o'erwhelming" was just too much for me.

* Or so you might think. Their are scholars out there - and I swear I'm not making this up - who genuinely interpret passages of the text to mean that Beowulf spent a lot of time killing walruses and even hippos. So why not frequent attacks by vicious turtles too ? Or great fires made out of turtles if we take 'balefire' literally ? Skip to page 15 for my thoughts on this.

I inserted a few missing words too : "messenger, I" became, "messenger, am I" which is hopefully not too Yodaish when read in the proper context. A minor change from the original text I'm using was to remove double hyphens and the colon/hyphen combination. Simpler formatting works just as well.

I've also kept the original notes that were present in the online text, but I've added a few of my own as well. Some notes have been removed entirely because they're pointless, while others have been edited. My own notes and the edits are clearly labelled.

Well, that's it. Start the appropriate soundtrack and go and read it !

But is it any good ?

What ? Oh, yes, I suppose I should say something about this while we're here. Yes, it is good, otherwise I would have given up the effort. But it's not really anything has sophisticated as Homer or Shakespeare except in terms of the aesthetics of the language. Characters are all (pretty much) zero-dimensional archetypes. Beowulf is a good Viking warrior who solves most of his problems by hitting things very hard, which he can easily do because he has the strength of ten men, thirty women, and at least three thousand hamsters. His men love him because he always does the right thing. Grendel is evil because that's just what Grendel is. The dragon is a big (15m, so about the size of a dinosaur) scary flying reptile that breathes fire and hoards gold, and that's it. Tolkein's Smaug would make short work of his literary ancestor. On the other hand, Smaug would never have existed without these much earlier stories.

But that's the thing, of course. Beowulf was written 1000-1300 years ago in Dark Age England - or possibly earlier with the single surviving manuscript being a transcription. This was not a time when people were into characters with complex moral ambiguity. Try reading the stories of the Mabinogion, for example, which Wikipedia describes as "fine quality storytelling". They're not. They're awful, full of characters who make no sense with random superhero abilities. Beowulf at least tells a self-consistent story of a brave hero slaying a demon, who then goes on to rule his people justly.

What it does have more in common with very contemporary stories is the need for backstories. It didn't work then, and generally it doesn't work now. Instead of telling a simple linear tale, every so often a character will talk at length about some other past battle, usually totally irrelevant to the current events. This is particularly confusing given the language - it's not always easy to tell where the story-within-a-story ends and we get back to the main tale.

But whatever weaknesses the language has to modern ears, its strengths are infinitely greater. This is poetry, after all.

| The Thirteenth Warrior, movie version of the Eaters of the Dead, is an under-rated adaptation with an epic soundtrack. |

Themselves had seen me from slaughter come blood-flecked from foes, where five I bound, and that wild brood worsted. In the waves I slew nicors by night, in need and peril avenging the Weders, whose woe they sought - crushing the grim ones. Grendel now, that monster cruel, be mine to quell in single battle !It quickly became clear that in order to have the Beowulf I wanted to read I was going to have to do it myself. What I want is something that has the beautiful language of the poem but reads more like prose. I don't want something that's full verse, nor reads as fluidly as modern prose. I want a challenging read, but not a struggle. It should feel old and archaic, but it doesn't have to be unintelligible.

I opted to take as light a touch as possible. It certainly won't please everyone, but that's not the point - I want something that I can read, and if anyone else enjoys it that's a bonus.

First, I removed those infuriating line breaks. I then had to create paragraphs because a wall of pure text is just awful. I also had to edit the punctuation, particularly commas. I don't know if it was the fault of the original poet, the translator, or both, but the original, poem has commas placed, more or, less at random, and far too often. I tried to do this only where I thought it absolutely necessary. Occasionally, I replaced some of the commas with hyphens to more correctly structure the sentence in prose form. Sometimes commas were replaced with "and" because it's just better that way. I also removed a lot of semicolons, as the original translation seems to have been written by someone who forgot they weren't writing Turbo Pascal.

The poet was wont to reverse the usual adjective-noun structure, so that a hardy warrior becomes a warrior hardy. Most of the time this is used to tremendous poetic effect. On a few occasions, however, I deemed it necessary to revert to the modern convention : an "atheling excellent" just doesn't make any sense in modern English. On even fewer occasions whole sentences sounded simply too much like Yoda-speak, and really quite ugly. The poet surely did not intend this, so very occasionally I edited the structure of whole sentences. This usually happens when the description of a character suddenly follows after what it is they've done (or even in the middle of a sentence describing what they're doing), which is distractingly confusing.

Words too I tried to preserve wherever possible, but I did make a few changes I found necessary (obviously, American spellings have been replaced with the correct British versions). Hrothgar cannot be called, "helmet of the Scyldings", because that sounds bloody daft : he's now their chieftain or king. One major change I did make was to replace "Geats" with "Weders", since I simply don't like the sound of, "Geats". It sounds too much like a goat-sheep hybrid. Historians probably won't be happy, but never mind.

A lesser replacement was to change "worm" to "wyrm" as I think the latter is more normally understood to refer to a dragon. "Beer hall" became "mead hall", again appealing the standard modern expectations of the Viking era. "Henchman" became various different words because it has far too many James Bond villainous connotations for modern use. "Recks" became "heeds" because the word works equally well and is more readily understood. "Gripe" usually became "grip" since the modern meaning is too different. "Hied" became "hurried". "Welkin" becomes either "sky" or "heaven". "Wyrd" became "fate" or "destiny". "Swan-road" became "whale-road" because it's found in alternative translations and sounds infinitely better. "Bale" usually becomes "bane", because bale is usually taken to mean a bale of hay (or a group of turtles, though that's not a very likely interpretation*). "Bairn" became "son" or "child", because bairn is no longer used outside Scotland. Wherever possible, replacement words were chosen to preserve the alliteration. And while I've mostly kept things like, "o'er", "o'erwhelming" was just too much for me.

* Or so you might think. Their are scholars out there - and I swear I'm not making this up - who genuinely interpret passages of the text to mean that Beowulf spent a lot of time killing walruses and even hippos. So why not frequent attacks by vicious turtles too ? Or great fires made out of turtles if we take 'balefire' literally ? Skip to page 15 for my thoughts on this.

I inserted a few missing words too : "messenger, I" became, "messenger, am I" which is hopefully not too Yodaish when read in the proper context. A minor change from the original text I'm using was to remove double hyphens and the colon/hyphen combination. Simpler formatting works just as well.

I've also kept the original notes that were present in the online text, but I've added a few of my own as well. Some notes have been removed entirely because they're pointless, while others have been edited. My own notes and the edits are clearly labelled.

Well, that's it. Start the appropriate soundtrack and go and read it !

But is it any good ?

| Artwork from the interweb. |

But that's the thing, of course. Beowulf was written 1000-1300 years ago in Dark Age England - or possibly earlier with the single surviving manuscript being a transcription. This was not a time when people were into characters with complex moral ambiguity. Try reading the stories of the Mabinogion, for example, which Wikipedia describes as "fine quality storytelling". They're not. They're awful, full of characters who make no sense with random superhero abilities. Beowulf at least tells a self-consistent story of a brave hero slaying a demon, who then goes on to rule his people justly.

What it does have more in common with very contemporary stories is the need for backstories. It didn't work then, and generally it doesn't work now. Instead of telling a simple linear tale, every so often a character will talk at length about some other past battle, usually totally irrelevant to the current events. This is particularly confusing given the language - it's not always easy to tell where the story-within-a-story ends and we get back to the main tale.

But whatever weaknesses the language has to modern ears, its strengths are infinitely greater. This is poetry, after all.

So yes, it's very good, if you like melodramatic language. Which I do. Don't read it expecting some great complex work that will give you deep insight into the English character. It isn't and it won't. What it is is a work of entertainment. Bugger any deeper analysis, it's just a bloody good read.Then flamed up to heaven the fiercest of death-fires, roared o'er the hillock, heads all were melted, gashes burst, and blood gushed out from bites of the body. Balefire devoured, as the greediest spirit, those spared not by war out of either folk : their flower was gone.

EDIT : Some years after doing this, I discovered Tolkien's magnificent essay explaining why Beowulf is indeed actually very sophisticated, in its own way. You can read my analysis of his analysis here.

Ask An Astronomer Anything At All About Astronomy (XXVIII)

Let there be questions ! And let there also be answers both sarcastic and true !

1) Are black holes doorways to another dimension ?

No.

2) How can we see the inner and outer planets at the same time ?

Because celestial mechanics, that's how.

3) How small a fraction of the deuterium was created during Big Bang Nucelosynthesis ?

All of it.

4) How about that spiral arms are density waves theory, eh ?

Yeah, it's great.

5) Which planets are the most and least spherical ?

Your mum.

6) Do solar winds keep star systems clear of dark matter ?

Dark matter isn't scared of no stupid stars.

1) Are black holes doorways to another dimension ?

No.

2) How can we see the inner and outer planets at the same time ?

Because celestial mechanics, that's how.

3) How small a fraction of the deuterium was created during Big Bang Nucelosynthesis ?

All of it.

4) How about that spiral arms are density waves theory, eh ?

Yeah, it's great.

5) Which planets are the most and least spherical ?

Your mum.

6) Do solar winds keep star systems clear of dark matter ?

Dark matter isn't scared of no stupid stars.

Sunday, 7 August 2016

Ask An Astronomer Anything At All About Astronomy (XXVII)

Questions, questions, questions...

1) Is the Orion drive really stupid ?

Only as stupid as your ugly face.

2) What's going on with Tabby's Star ?

Many things.

3) Shouldn't Dyson spheres be resistant to heat and hard to detect ?

No.

4) Could the ISS catch an astronaut if their tether broke ?

No.

5) Could the dimming of Tabby's Star be due to comets or sunspots ?

I dunno. Maybe.

1) Is the Orion drive really stupid ?

Only as stupid as your ugly face.

2) What's going on with Tabby's Star ?

Many things.

3) Shouldn't Dyson spheres be resistant to heat and hard to detect ?

No.

4) Could the ISS catch an astronaut if their tether broke ?

No.

5) Could the dimming of Tabby's Star be due to comets or sunspots ?

I dunno. Maybe.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)