Some words are well-known for meaning different things to scientists and the general public. "Theory" is supposedly one of those, "skeptical" is another. The reality is that even within science, these words are used in a multitude of different ways that's often context dependent. If I say to my colleagues, "it's only a theory", they will not shout at me for deriding the value of a hard-won scientific discovery - that is a purely fictitious idea manufactured by the internet. It's true that theory does have that special meaning, but it isn't used this way with any special rigour or even any rigour at all. Indeed, "theorist" is routinely used as a term for anyone who spends more time on ideas than observations, not someone who continuously constructs amazingly well-tested models.

"Bias" is a bit different. The common meaning is something like an unintended, unreasonable preference : "you're only being mean to my pet tortoise because he bit you once !". And indeed, if said tortoise hardly ever bites anyone, it wouldn't be reasonable to avoid them forever. But in science, a bias can not only be a good thing, it can be essential.

Science is biased ! Oh noes !

Suppose you wanted to discover a tortoises' favourite food. Well, that's easy, you just take your friend's tortoise, plonk down a load of stuff he likes to eat down and... no. That answer isn't even wrong, because the question was silly. You need to be more specific. Try : of all the available food in the house, what does Tim the tortoise like to eat best ? That question you can answer. Determining Tim's favourite food would, technically, involve Tim sampling every food on the planet - but limiting it to what's currently available is a solvable problem.

Which is no excuse to be an areshole whenever someone says their favourite food is "blah", because you bloody well know what favourite means in this context. Or at least you should. I had a friend who was annoyed whenever people said they didn't like rap music, as though they'd listened to all rap music. Which was a very unfair assumption. Obviously a) the statement usually just means, "I don't like all the rap music I've ever heard but it's self-evident that I can't really judge music I haven't heard, duuuuh !" and b) if there's something intrinsic about the style of monotone talking over music that annoys you, chances are you're not gonna like any rap music. Your inference that you don't like any and all rap music may not be 100% iron-clad certainty, but it's a perfectly reasonable extrapolation for everyday life. You're not "biased" against it, you genuinely don't like it.

But suppose you did want to discover the favourite food of the tortoise. Not just Tim but the general preference of all tortoises. OK, let's make this easier and restrict it to, say, the Magnificent Eurasian Tortoise, found all across Europe and Asia and known for its golden carapace and acute financial acumen. Now, if you wanted to find the favourite food of the tortoise in the wild, how should you choose a sample of tortoises to examine ? Should you look only at those in Europe which are easiest to catch ? Should you instead look at the more active tortoises of the Asian steppe, which can run away at tremendous speed and therefore eat more ? Should you only look at very young or old tortoises or a mixture of the two ?

| And should you limit your selection to tortoises with rocket packs ? |

The more specific your question, the more meaningful your answer. There might not be a favourite food of the species as a whole because its geographic distribution is so large - different tortoises eat different things depending on what's available. But tortoises might, conceivably, have subtle differences such that Asian tortoises genuinely prefer different foods to the European ones. You'd have to give them both samples of the other's food. And you'd have to try it with hatchlings and raise them over many decades then try swapping their food, to be sure they just hadn't got used to some foods in order to tell if it was really an innate, genetic difference or not. Complicated, isn't it ?

So what you do is deliberately bias your question and your sample to get a meaningful answer. You abandon your mad obsession with finding out what tortoises really like to eat and instead limit yourself to determining what they do eat in specific geographical regions at different ages. So you monitor a large sample of tortoises across Europe and Asia and record as much information about them as you can. Afterwards, you split your sample based on things like location, age, gender, and weight, and compare what they actually do eat with what they potentially could eat in each region. Only then can you begin to say useful (?) things like, "young tortoises in Europe mostly eat lettuce whereas those in Asia tend to prefer cabbage, but old tortoises all love carrots regardless of age, location or any other factor".

Had you gone charging in without any of this, you might have just picked a representative sample of tortoises - that is, one that consists of tortoises of all different sizes, ages and genders in roughly the same proportion as in the total population - and said something daft like, "the Magnificent Eurasian Tortoise's favourite food is cabbage." That might be the case overall if the whole population consists mainly of Asian tortoises of a certain age, say - in this case your "representative" sample is actually biased. You, in your thoughtless stupidity, have failed to account for the subtleties of statistical analysis.

The trick to getting a meaningful answer is not to eliminate bias, but to ask a specific question and bias the sample appropriately. It's very much easier to address, "what's the favourite food of young European tortoises ?" because you know exactly what sample you need; a representative sample of the entire tortoise population would give you completely the wrong answer. Bias can be essential.

Scientific bias can also be purely accidental. If didn't go and measure the tortoises yourself but were just given the raw data, you might choose to analyse a sample that inadvertently contained a bias you wouldn't have anticipated. For example if you were interested in what made tortoises obese you might select the fattest 10%, say. But if they all happened to come from the same geographical area, there might be a unique factor at work - so you'd never work out the true cause of tortoise obesity in most cases.

For these reasons, scientific bias is sometimes referred to as a selection bias or selection effect. It isn't necessarily good or bad and doesn't imply the researcher screwed up or wants to prove their pet theory. Those sorts of bias do happen in science, obviously, and that's what most people mean by bias in everyday conversation.

Everyday bias

Bias and discrimination isn't always unfair. Giving the job to the best people may be biased towards the most educated or the physically strongest, but that's hardly unfair if you're looking for someone skilled in advanced mathematics or a manual labourer. What would be unfair is not giving everyone the same opportunities to pursue those careers in the first place - to say, "no, you're ginger, you can't learn maths." Discriminating on merit is fine as long as everyone's had a chance to compete fairly.

Then there are cases where even an unfair bias is perfectly understandable. Of course people will be surprised if a 100 year old competes in a marathon and no-one would expect them to win. Ostensibly you could just let them enter and wait and see what would happen, but the link between fitness and age is so well-established that expecting them to win would be a little bit mad. You might even suggest, not unreasonably, that perhaps they should be subjected to medical checks you wouldn't ask of younger competitors, for their own safety. Would that really be unfair ? I don't know, but it's certainly a grey area (you probably wouldn't stop them actually competing, though, unless you found a good medical reason beyond "they're very old").

So you might also be forgiven for thinking that perhaps making regulations which restrict the movements of those more likely to commit crimes is understandable. And to some degree, it is. If you insist on shouting incredibly loudly about the crimes of one particular group while labelling them in a different way to the crimes of another - Muslims are "terrorists" whereas gun-nuts are "lone wolves" - then of course people are going to believe there's something different about that group. Especially if you essentially never bring up their religion except when denigrating them as terrorists, omitting that suddenly "irrelevant detail" when they make the news for other reasons. Legitimate, entirely politically correct criticism of individuals so easily transmutes into a witch hunt.

Here the bias of the media is abundantly evident. There's no good statistical reason to fear Muslim "terrorism" over any other kind of homicide, and indeed in the USA (see figure below) this is positively deranged. Now, at this point one may say, "but Muslim culture blah blah blah" or, "the Koran says blah blah blah", as people often do. OK. That's absolutely fine, but it's a completely different topic to whether or not one group is measurably safer than another. If you want to talk about preventing terrorism, there can't be any debate about that. In America you're far more likely to be shot but a non-Muslim nutcase; in Europe it's true that most recent terror attacks have been caused by Islamic extremists... but the number of dangerous extremists is such an insanely tiny fraction of the community it makes no sense to be scared of them as compared to any other ethnic or religious group. So I can understand why you'd be concerned, but that doesn't mean you're not just flat-out wrong.

For a final example let's look at the recent "Muslim ban" from a different perspective : not whether the ban is right or wrong, but how supporters and detractors view each other. In my opinion, the continuous depiction of the other side as "biased", as though at inevitably means they're just wrong and untrustworthy, is one of the most dangerous tools in political debate. As we've seen, being biased doesn't always mean you're wrong - so long as you understand that bias. But is there an unfair perspective at work here ? Is one side resorting to double standards, engaging in mass hysteria because Trump instigated a ban but completely ignoring Obama's earlier, similar restrictions ?

Let's make two simplifying assumptions here just for the sake of argument. Let's suppose, in defiance of the actual facts, that there was a good reason to be suspicious of Muslims but the case wasn't yet proven. Let's also suppose that Obama and Trump's bans were identical and explicitly targeted at Muslims, which is also factually wrong. Don't worry, well return to the actual bans shortly.

If you were to say, "President Obama's Muslim ban was bad because Obama is a bad person, but Trump's ban is good because Trump is a great man and he can do no wrong", then you are irredeemably biased and unprincipled. You are supporting a policy not based on that policy itself but on who enacts it. If, however, you were to say, "I support Obama overall, but the Muslim ban was an inexcusable failure. I campaigned against it and will do the same against Trump's ban." then you are not biased. You are judging the policy based on the policy itself, and while you may still be an Obama supporter you aren't trying to excuse one particular action you don't like.

The flip side of this is that you could be unbiased on the other side. You could say, "I didn't vote for Obama but I supported his Muslim ban because it was the right thing to do, and I support Trump in part because of this policy". That's not biased or unprincipled either. I personally wouldn't support your principles in this case, and would in fact strongly object to them, but I will acknowledge that you have them.

It's also important to recognise that there can be degrees of bias. You could say, "I think Obama is just trying to do the right thing and though this ban is a failure of principle, this might be a time when unusual measures are required." In this case you've partially abandoned your principles for the sake of the man : you're prepared to support a policy that you don't really approve of, but you're honest enough to admit that.

It's the difference between saying, "I support Trump so I support a ban on Muslims", and, "I support a ban on Muslims so that's why Trump has my support". The former is biased, the latter principled - even if we might not like those principles.

aren't quite like these simplifying assumptions. For starters it's apparently not a Muslim ban; while technically true this is a clear example of political bullshit since that's how it was unambiguously described in the election campaign. The bans also differ in their scale and execution : the Obama administration's limited to a single country versus Trump's seven (as opposed to the previous which visa waivers from seven countries were made more difficult to obtain, which is not the same as a ban at all); Trump's including green card holders who were already extensively checked for eligibility to reside in the US, but now, at the stroke of a pen, excluded.

But the crucial difference is the preliminary rhetoric to the ban. Obama never made a ban on Muslims a major part of his campaign policy, and was in fact well-known for speaking out against discrimination. He also didn't institute the ban as an executive order either, though he did fail to veto it. Only the most extreme Obamaphiles would attempt to defend the Obama ban while decrying Trump's; the rest of us should see it as a failure.

But what was seen as a failure of the old administration is being touted as a triumph of the new - Trump didn't merely allow the ban, he encouraged it, enacted it as an executive order, and promoted it with discriminatory rhetoric. So it is wholly unfair to accuse all but the most extreme liberals of bias or double standards here - of course people are going to react differently when discrimination is promoted as a success rather than (at most) an excusable failure. Compared to this, even the important difference of Trump's ban affecting green card holders looks relatively minor, as does its shoddy execution.

So no, it's not fair to accuse the left of bias against Trump in this case. First, the need for the ban is flatly contradicted by the facts - and there's nothing the slightest bit unfair about being biased towards the facts. That's a case of perfectly sensible bias, as we saw happens all the time in scientific analysis. Second, the bans were different in scale, execution, and most importantly of all in stated intent. The latter turns the issue from one of "things I don't like" into "things I'm morally opposed to" - and few would deny anyone the right to protest over things they have moral objections to.

Conclusion

|

| We're not all just grumpy for no reason. |

Outside science bias has much more negative connotations, as though the other researcher suspected you of sampling the data in a way designed to deliberately mislead. Or that you only try and defend something or someone because of some pre-existing preference : a prejudice. Currently the political scene feels like little more than each party and its supporters accusing the other of "bias" (and its next of kin, "double standards") no matter what the situation.

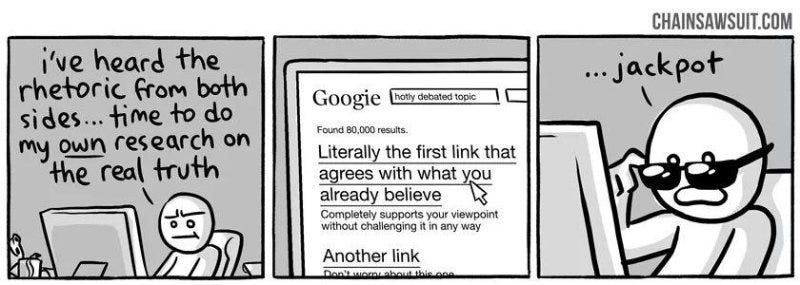

This is dangerous. We're no longer looking at why people don't like the opposite position, we simply assume that because they don't like it they must be wrong. Brexiteers seem to fall victim to this like no other. Not a single one has presented me with a credible argument for leaving : they just go and say, "you don't get to ignore the vote result just because you don't like it", as though I had no actual reasons for not liking it at all. Yes, I prefer one argument to another. I am not impartial. That does not automatically equate to me being "biased", in the unfair sense, or being wrong, because you can damn well be biased for and against the facts. We've degenerated into endless bias wars, never really attacking the actual arguments at all. So I like to remember a useful quote :

Ironically enough, I can't stand Richard Dawkins. I guess I must be biased.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Due to a small but consistent influx of spam, comments will now be checked before publishing. Only egregious spam/illegal/racist crap will be disapproved, everything else will be published.